After Afghanistan, the economy is the next Biden catastrophe

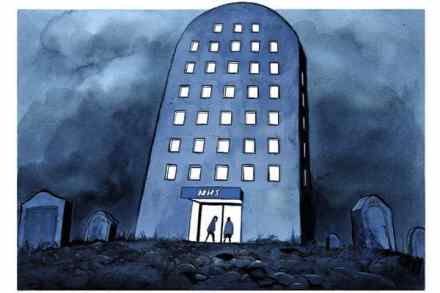

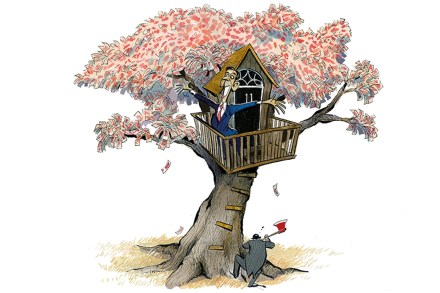

The debacle in Iraq. The fall of Saigon at the end of the Vietnam War. The failed ‘Bay of Pigs’ invasion of Cuba. You can debate where exactly the collapse of Afghanistan ranks in the list of American military and foreign policy disasters. But one point is surely certain. It is a major setback, and one that will undermine the credibility of the United States for years to come. Here is the real problem, however. It is not going to end there. The economy will be the next major catastrophe of Joe Biden’s increasingly chaotic presidency. Biden has embarked on a drive for a bigger state, with more control over