How a humiliating defeat secured Britain its empire

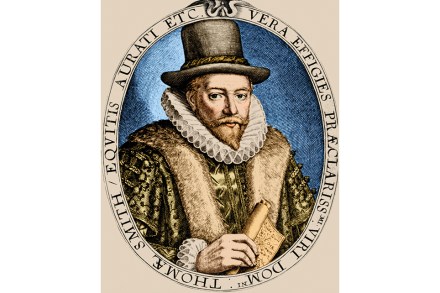

Beneath a flinty church tower deep in the Kent marshes, ‘among putrid estuaries and leaden waters’, lies a monument to an Elizabethan man of business. It is not much to look at. David Howarth calls it ‘second rate… dull’ and ‘strangely provisional’, despite its expanse of glossy alabaster. Moreover, the name of the man commemorated will ring few bells, even among historians. But it is the only memorial erected to one of the most important men in English history. Sir Thomas Smythe was perhaps the greatest businessman in Elizabethan England. He not only founded the East India Company; he also played a leading role in several other significant commercial and