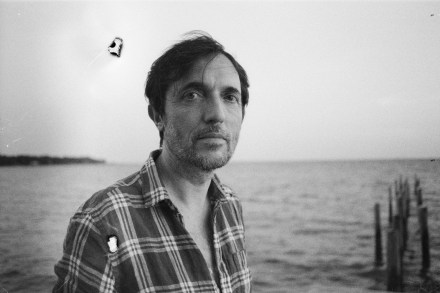

The perils of poaching: Beartooth, by Callan Wink, reviewed

Beartooth, the second novel by the Montana-based writer Callan Wink, opens with two brothers elbow-deep in the viscera of the third black bear they have just shot out of season. Hazan’s hands are ‘moving around the hot insides of the animal as if he were rummaging through a junk drawer’. He wants the gallbladder, which will fetch around $1,500 – far more than the brothers get for chopping firewood. The skull, claws and skin will swell their illegal bounty by another $500. Thad and Hazan, aged 27 and 26 respectively, are in serious debt after their father’s recent death, and their roof is leaking. Logging in the Montana backcountry is