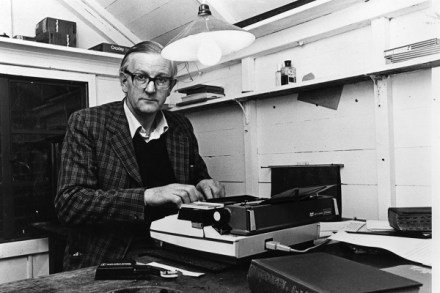

Tom Sharpe nearly killed me

I was on a train when it happened. I was bent double with my head between my knees, gasping for air and unable to speak. The Surrey matriarch sitting opposite leant forward to ask me if she could help. I imagine she thought that I was choking, or perhaps suffering cardiac arrest. In fact, I was laughing. Laughing so hard I couldn’t stop. And the more I wanted to stop, the worse it got. It was painful. My lungs rasped and the muscles in my sides contracted of their own free will. I was no longer master of myself, so you might say that I was in ecstasy. It was