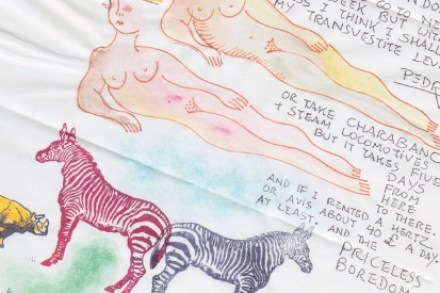

What’s to become of Pedro Friedeberg’s letters?

The year 2015 has been designated one of Anglo-Mexican amity, with celebrations planned in both countries by both governments. But it looks as though one name will be missing from the list: Pedro Friedeberg’s. ‘Who?’ you may ask. Well, in 1982 I was in Mexico City to interview Gabriel García Márquez after he’d won the Nobel Prize for Literature. At a party given by a Mexican art-collector, I noticed several zany pictures on the wall. ‘They’re all by Pedro Friedeberg, my favourite Mexican artist,’ said the collector. I stared at one large framed square after another, at pictures in which the Old World and the New seemed conjoined in a