Dirty dealing across the board

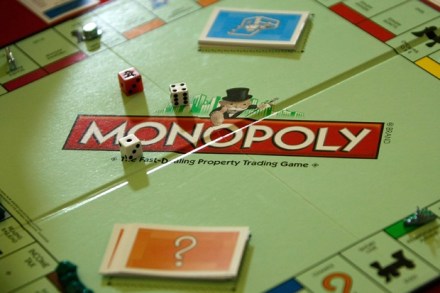

I knew there had to be a point to Monopoly. The game itself is tedium made cardboard, the strongest known antidote to the will to the live. There is a 12 per cent chance that any given game of Monopoly will go on for ever (the other 88 per cent just feel like that). In fact I’m still not convinced that the name isn’t a spelling mistake. The story of Monopoly, on the other hand — now there’s a thing. Specifically, the story of how it was invented. For decades the accepted version had down-on-his-luck Charles Darrow creating the game in the 1930s, as entertainment for his impoverished family and