Ghosts of No. 10

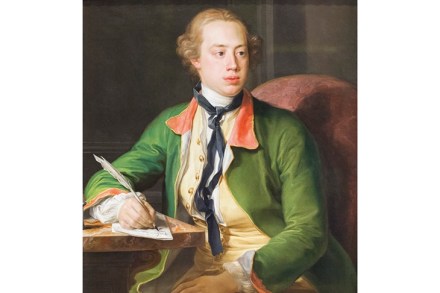

If you associate Lord Salisbury more with a pub than with politics, here is Andrew Gimson to the rescue, with succinct portraits of every prime minister to have graced — or disgraced — No. 10 to date. You will find no trace of waspish mockery in his book. In a time when heroes are constantly being debunked, its kindly, intelligent tone appears refreshingly old-fashioned. The flamboyant Robert Walpole makes for an ideal scene-setter. In 1721 he invented the office of prime minister and held it for longer than any of his successors — a full 21 years. Plump, affable and crude, with an astute business sense, he managed to amass