Spectator competition winners: poems about struggling to write a poem

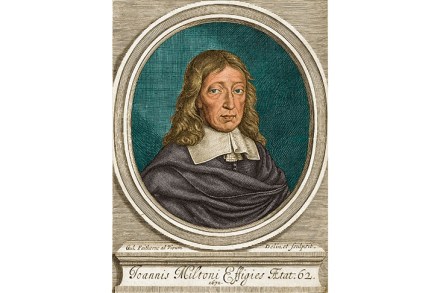

The call for poems about the difficulty of writing a poem attracted a far-larger-than-usual entry. A.H. Harker’s punchy couplet caught my eye: I’m stuck. Oh ****. Elsewhere there were nods to Wordsworth, Milton and ‘The Thought Fox’, Ted Hughes’s wonderful poem about poetic inspiration. The winners below earn £25 each for their travails. Brian Allgar I struggled with my verse time after time, Yet somehow I could never make it work. It scanned quite well, but there’s no use pretending My couplets had a satisfactory finish. The words at their conclusion never matched; They would not rhyme, however hard I rubbed My head. The wretched quatrains fell apart, And I