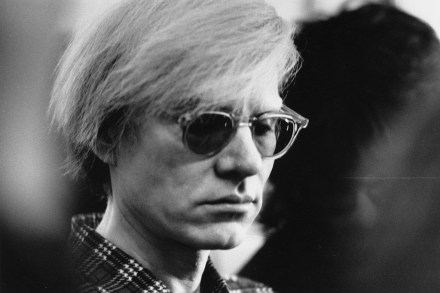

The warm, generous side of Andy Warhol

33 min listen

On this week’s Book Club podcast, I’m joined by Blake Gopnik — the author of a monumental new biography of Andy Warhol. Blake tells me how everything — fame, money, and other human beings — were ‘art supplies’ to Warhol, but that underneath a succession of contrived personae Warhol could be warm, generous and even romantic; that the affectlessness of his art was not the expression of an affectless man; and that if he’d lived on, Gopnik thinks, he could have produced something equal to the late work of Titian.