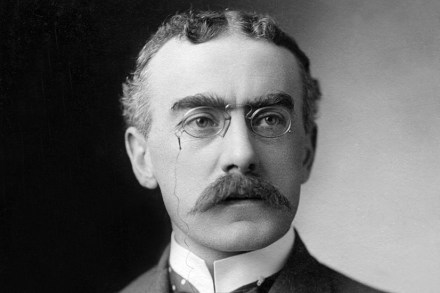

Never a dull sentence: the journalism of Harry Perry Robinson

Is Boris Johnson a fan of Harry Perry Robinson? If he isn’t, he really ought to be. Reading this absorbing biography, I was struck by how much they have in common — especially in their early lives. Both men went to public school, then on to Oxford, then into journalism, where they proved incapable of writing a dull sentence. They both divorced and remarried — and were also American citizens, for a while. Both dipped a toe into politics, but while Boris took the plunge, Harry stepped back and remained a jobbing hack until his dying day, the finest journalist of his generation. The biggest difference, however, is that Harry