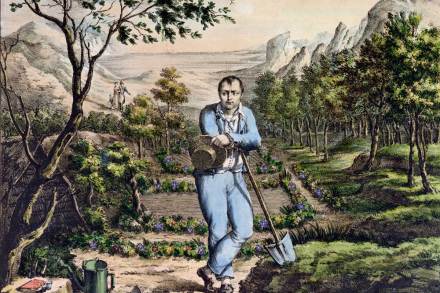

Straight lines and grandiose schemes — Napoleon the gardener

On 1 January 1806, a little over one year after his coronation, the Emperor Napoleon ordered the abolition of France’s new republican calendar and a return to the old Gregorian model. Over the past seven years republicans had grown used to ‘empire creep’, but even for those who had been forced to watch the principles of the revolution dismantled one by one and a republican general metamorphose into Emperor of the French, this last insult carried a peculiarly symbolic charge. For all its engaging dottiness — each new year, coinciding with the autumnal equinox, would begin on a different date — the short-lived republican calendar had embodied some of the