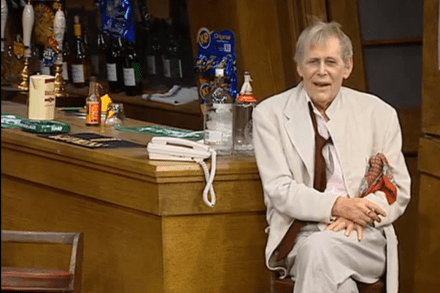

The man who transformed houses

Alec Cobbe is a designer, painter, musician, picture restorer and collector, and has recently donated drawings, photographs and other archives to the V&A, where some of this collection is now on display. Cobbe was born in Dublin and aged four moved to the family house Newbridge, an 18th-century, 50-room country villa designed by James Gibbs, which, he says, was the ‘single greatest influence on my life’. He had an ‘idyllic lamp-lit childhood’ — there was no electricity — where the ‘running water was rainwater, which had to be pumped daily to a tank at the top of the house’. And to keep young Alec amused there were pictures, historic interiors