The bombshell official review into the Government’s anti-radicalisation Prevent programme will land on desks in Whitehall today – but will, as politicians like to say, any lessons be learnt? Its author, William Shawcross, is reported to have been bold in highlighting the deficiencies of the scheme, which, he says, has ‘failed to tackle the ideological beliefs behind Islamist extremism with potentially serious consequences’.

The review was commissioned three years ago by Priti Patel, a woman who styled herself as a no-nonsense home secretary, but who proved nothing of the sort. Her successor, Suella Braverman, also likes to talk tough. Shawcross’s report has set her the challenge of proving her resolve in confronting the challenge of Islamic extremism.

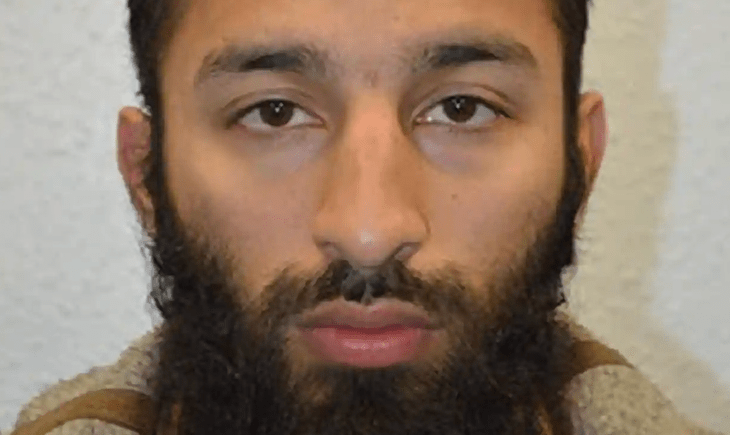

We don’t need a review to tell us what has gone wrong: several terror attacks in recent years were perpetrated by extremists who had been referred to Prevent, including Usman Khan, who murdered two people at Fishmongers Hall in 2019, and Khuram Butt, the ringleader of the jihadist cell that killed eight people at London Bridge in 2017.

Britain has few experts on Islamism compared to France and even fewer who are brave enough to put their head above the parapet

Shawcross accuses the programme of being too touchy-feely with extremists referred to Prevent. ‘Whilst safeguarding rightly sits as an element of Prevent work,’ he writes, ‘the programme’s core focus must shift to protecting the public from those inclined to pose a security threat. Prevent too often bestows a status of victimhood on all who come into contact with it.’

Among his recommendations is an overhaul of the programme to return it to its ‘core mission’ of preventing people carrying out terrorist acts. In recent years, Prevent has been too focused on right-wing extremism at the cost of doing more to tackle Islamic fundamentalism. Shawcross attributes this to a fear of ‘being (seen as) racist, anti-Muslim or culturally-insensitive’.

The Home Secretary is expected to accept all the report’s recommendations. In her statement to the Commons, she is set to announce that Prevent must focus on extremists’ dangerous ideology and not their mental health.

There will, inevitably, be howls of outrage from some of those on the left; there will also be cries of Islamophobia. That is what happened in 2016 when Greater Manchester Police staged a simulated terrorist attack in a shopping centre. The man playing the suicide bomber shouted ‘Allahu Akbar’, and all hell broke loose.

‘This sort of thing panders to stereotypes and further divides us,’ said the Community Safety Forum, an anti-Islamophobia organisation, one of many complainants who forced GMP into an apology. ‘It was unacceptable to use this religious phrase immediately before the mock suicide bombing, which so vocally linked this exercise with Islam,’ the force said in a statement.

Twelve months later an Islamist suicide bomber detonated his device in the Manchester Arena, killing 22 people, the youngest a girl of eight. At the subsequent inquiry a security guard in the Arena admitted he harboured suspicions about the killer in the minutes before the attack, but did not approach him because: ‘I did not want people to think I am stereotyping him because of his race…I was scared of being wrong and being branded a racist.’

Last year, Manchester singer, Morrissey, released a bitter song about the Arena attack, entitled ‘Bonfire of Teenagers’. It includes the lines: ‘And the silly people sing: “Don’t Look Back in Anger/And the morons sing and sway: “Don’t Look Back in Anger” /I can assure you I will look back in anger ’till the day I die’.

Millions of Britons feel the same way, a dull visceral anger at a political class that for years has been in denial about Islamic extremism. Theresa May nervously suggested in June 2017 after the Manchester and London Bridge attacks that Britain would ‘require some difficult, and often embarrassing, conversations’ if it was to combat Islamist ideology. We’re still waiting. Indeed, when Tory MP David Amess was murdered by an Islamist in 2021 – another man who had been through the Prevent programme – barely anyone in the Commons could bring themselves to mention Islam; instead some sought to pin the blame on social media.

Three months after May’s ‘embarrassing conversations’ speech I wrote on Coffee House of my despair that the PM and other Western leaders still seemed to ‘believe that in the end the Islamists will come round to our way of thinking and embrace our set of values.’

To shake them from their naivety I suggested they read a recent French book, Les Revenants (The Undead), in which the author, David Thomson, interviewed dozens of French jihadists who had joined Islamic State. Only one expressed any regret from his prison cell. A female Islamist, Lena, explained to the author that the slaughter of the Charlie Hebdo cartoonists for blasphemy in 2015 was a ‘beautiful’ day. She ridiculed the West for its belief that Islamism was just a youthful phase. ‘It’s funny’, she said. ‘They talk to us as if we’re life’s losers…but for me, deradicalisation is just some fancy new word they’ve dreamt up’.

Emmanuel Macron has addressed the problem of Islamic extremism with more diligence than his predecessor François Hollande. Among his advisors on the subject is Gilles Kepel, an Arabist who has been writing about the Islam in the West since the 1980s. There is a significant distinction between France and Britain in confronting Islamic extremism: the French are prepared to have those ‘difficult, and often embarrassing, conversations’, many of them initiated by Muslims, displaying great courage in speaking out against the extremists. The term ‘Islamophobia’ was discredited in France a decade ago when the then socialist PM Manuel Valls, dining with Muslims at the breaking of the Ramadan fast, described the term as the extremists’ ‘Trojan Horse that aims to destabilise the Republic’. In Britain, in contrast, the fear of being labelled Islamophobic has terrified all but a few brave souls into silence.

One of the recommendations proposed by Shawcross in his report is that Prevent advisory boards should include experts on the ‘ideological drivers of terrorism’ to challenge the depiction of ‘radicalisation as an illness’. But Britain has very few experts on Islamism compared to France and even fewer who are brave enough to put their head above the parapet.

Ed Husain is one. His 2021 book, Among the Mosques, described an extremist ideology that ‘is anti-Western and seeks to subvert British culture, laws and institutions.’ The book appalled the chattering class. One reviewer in the Financial Times complained that ‘Husain’s reflex is always to blame minorities for not assimilating, rather than challenging prejudice and iniquity’. There writ large is the ‘status of victimhood,’ identified by Shawcross in his report.

Those of a cynical disposition will have little faith that any of the recommendations in the report will be implemented. There will be the customary pledges by ministers on television and radio over the coming hours; perhaps an op-ed in a newspaper; and then the report will be quietly shelved.

‘Let no one be in any doubt that the rules of the game are changing,’ declared Tony Blair in the wake of the London bombings of 2005 that left 52 people dead. But the rules didn’t change. Extremists have continued to wage a campaign of terror. They’ve used knives and bombs, but sometimes words are enough. Remember the Batley schoolteacher? He’s still in hiding two years after he was threatened with death for showing a cartoon of the Prophet in a classroom discussion about free speech. Few came to his defence. He was abandoned by a Britain that has been cowed into submission by the terror of being called Islamophobic.

Comments