Before the year ends, I’d like to tell the story of Karol Sikora and attempts to have him removed from a Spectator-sponsored discussion on the NHS at the last Tory conference. It offers an insight not just into how we work at 22 Old Queen Street but the dynamics of sponsored discussions.

The Tory conference has become the Edinburgh Festival of political discussion: a place where ministers, activists, advisers, corporates and journalists converge to discuss pretty much everything. As with Edinburgh, the real action is on the fringe rather than the official lineup. When I became editor in 2009, The Spectator had no presence at the conference; now we host about a dozen discussions and a party. Our ground rules: to do interesting debates on important issues, with a variety of voices – the debate is robust, but enjoyable . We don’t do sanitised or dull and pride ourselves on events with long queues that people talk about afterwards.

The sponsor of the discussion had a condition: no Sikora

Sometimes, what the sponsor wants is too niche for a general audience or not really a debating issue: in which case, it’s not really a Spectator discussion. We want to discuss the questions that matter. A classic example was a debate in the last Tory conference: ‘How to fix Britain’s cancer crisis?’ The lineup was Elliot Colburn MP, vice chair of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Cancer, Dr Katharine Halliday, president of the Royal College of Radiologists, Dr Owen Jackson from Cancer Research UK and Prof Karol Sikora, perhaps Britain’s best-known oncologist. It was also sponsored.

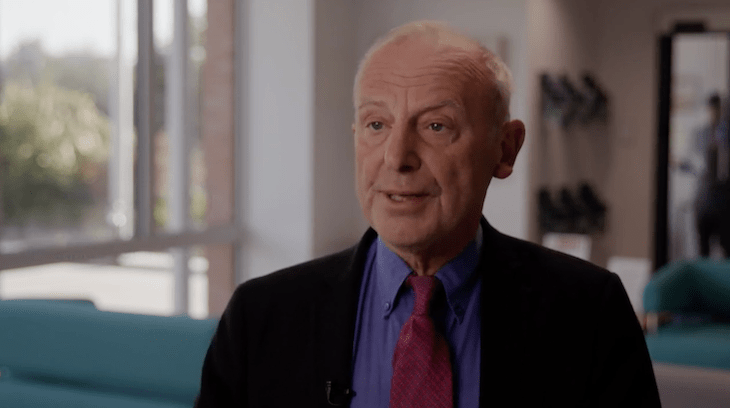

But the sponsor had a condition: no Sikora. Why? We tried to be open-minded and work out the sponsor’s concerns. Fair enough if we had found a loudmouth doctor with no cancer experience, or a bad communicator. But Sikora’s credentials are impeccable. He’s eloquent, has 40 years’ experience and is a former director of the World Health Organisation’s Cancer Programme. The sponsor said he did not align with its “values”: that he was too controversial, too political. Again, odd: he has lambasted both Labour and Tories in the past so he’s hardly parti pris.

But he has been a critic of the NHS, and it soon became clear to me that this was the issue. The sponsor was an NHS supplier and leery about platforming an outspoken heavy-hitter likely to deliver a few home truths about NHS failings. I can see the logic: which NHS supplier can afford to annoy the NHS, a behemoth and number one purchaser of health services in the country? So we ended up with a choice: keep Sikora, or keep the £25,000 of sponsorship.

We could easily have dropped him. So sorry, professor, we have overbooked. Come back another time! All we’d have to do is go down to three panellists (plus the sponsor) or find another, bland oncologist. No one would ever know. But not for a second did we consider cancelling Sikora. The Spectator is about promoting wide and vibrant debate or it’s about nothing. How could we have a debate about Britain’s awful cancer rate without discussing the elephant in the room of NHS structure? I’d argue that the UK’s woeful cancer record is, in part, caused by a refusal to discuss such questions.

This little drama made it clearer to me why we’re in this mess. It’s not just corporates: Labour and Tories both dislike criticising the NHS. It’s so massive that to criticise any small part of it can be seen to attack all of it – and in Britain we deify it, clap for it, regard it (as Nigel Lawson famously said) as a religion. This makes candid debate difficult. People like Sikora are seen to be beyond the pale if they have ever argued that NHS structure impedes cancer care. Imagine what effect this could have on junior doctors, or others wanting to debate important issues within a hierarchy that they seek to climb.

Sikora’s position is quite nuanced. ‘There’s nothing wrong with the NHS doctors, nurses or technology, they are fantastic,’ he said afterwards. ‘It’s the management and the whole structure that is wrong. Not always at a local level, but NHS England is filled with highly-paid people that essentially do nothing and cause problems in the system. Anybody can recognise that we don’t need more money for the healthcare system, we need better management.’

I suspect that this is the disallowed opinion: that reform, not more money, is needed. Many may disagree. But if we cannot let respected oncologists make this point at a conference for the governing party, what’s the point of debate? Why are people even at Tory conference? The role of journalism is to promote debate, not curtail it. What we were being asked to do – censor a dissenting expert – would have been a breach of our values. I tried to explain this to the sponsor, and it took a while for them to work out what we were saying: that they, not Sikora, were being dropped from the cancer discussion panel.

In this way, Sikora became the most expensive speaker in The Spectator’s history, insofar as it cost us £25,000 to keep him. Not that dumping him ever crossed our mind. I should add that our colleagues in the advertising department are our great allies in this regard: I never faced any pressure to disinvite him. As editor I’m involved in pretty much every discussion about conference debate titles and panels: we care about our debates as much as we do our articles. The advantage of being a small outfit is that all of us in 22 Old Queen St know each other and work closely together: the sponsorship, editorial and events teams all understand The Spectator‘s remit and purpose.

In any other publication, the sponsorship team might complain to the management that editorial are being inflexible and un-commercial: there are budgets to hit, etc. But at The Spectator, final decisions are made by our chairman, Andrew Neil, who took approximately 0.1 seconds to agree that Sikora should stay and the sponsor should be cancelled. What’s the point in making money, he said, if we cannot protect our principles?

As an editor, I’m lucky in having the business side of The Spectator run by Andrew Neil who, when he hears that an advertiser is protesting about a columnist, will ban the advertiser (as he did with the Co-op). We even returned the furlough money to the taxpayer as soon as it became clear that we didn’t need it: at the time, according to the Treasury, we were the first company in the UK to offer to do so. (They didn’t even have a mechanism for furlough return, so at one stage we were considering dumping bags of money on the Treasury’s doorstep.)

I should also add, here, that I understand and respect the sponsor’s logic. The NHS is a near-monopoly: many of its suppliers are understandably fearful of getting on its wrong side. That’s why most healthcare companies shy away from controversy and robust debate. I mention this story because, while our response was usual, the request will not have been – and we need to bear this in mind when considering how NHS debate is conducted. And why more open debate will be needed if we’re ever going to have the proper wide-ranging conversation that patients (and those who treat them) deserve.

PS If you’re not a Spectator subscriber and would like to try us free for a month, click here

This article is free to read

Subscribe and get your first month of online and app access for free.

Comments

Join the debate, free for a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first month free.

UNLOCK ACCESS Try a month freeAlready a subscriber? Log in