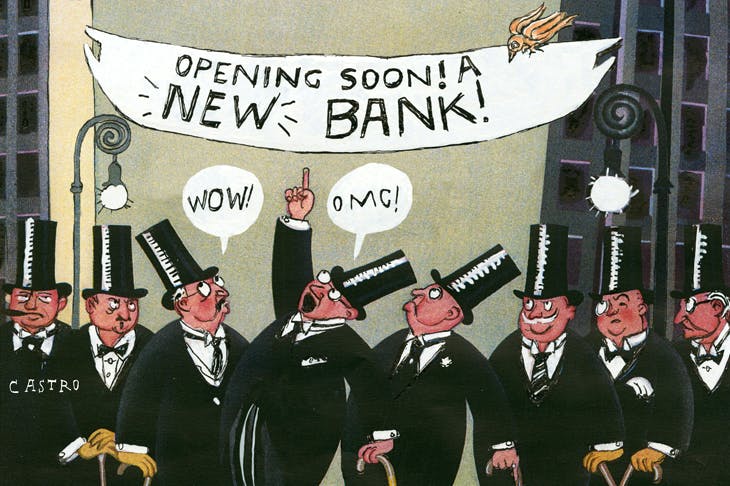

Looming behind the Frost-Barnier negotiations is a battle between London and Paris as financial centres. After the June 2016 referendum, the French failed miserably to seduce City institutions away from the UK. There was no exodus from London, and of those few relocations to the continent, most avoided Paris, preferring to scatter widely from Dublin to Frankfurt and Amsterdam.

After failing in the first instance, the French will now attempt to do so by force under the cover of the EU negotiations. The strategy of Macron and his ambitious Finance Minister, Bruno Le Maire, will be to ensure Europe does not recognise passporting for British banks, that Euro-denominated transactions are no longer cleared in London, and that a system of regulatory equivalences with the UK is as bare as possible. So says the French Senate’s European affairs committee in a 2 March 2020 resolution setting out the terms the French government must require in the negotiations.

The lever for relocating business to Paris will be the European Banking Authority, now transferred from London to Paris, around which the French will hope to cluster ex-London institutions. However, even the French know that this maximalist position will be hard to sustain given London’s financial ecology, its firepower and importantly Paris’s drawbacks. A number of highly detailed French Senate reports into Brexit in the last couple of years spell this out.

‘For whoever controls norms also controls the market’

‘The US innovates, the Chinese copy and Europe regulates’, so quipped the former president of Italy’s CBI. But she overlooked the source of Europe’s regulatory urge: France. In the name of universalism and equality, the French have long attempted to regulate everything.

Hardly surprising then that a 2017 French Senate report on Brexit devotes a whole section to the regulatory handicap confronting Paris in wishing to attract business from London. The internationalisation of Paris as a financial centre, it states starkly, is penalised by the unsuitability of its fiscal, social and regulatory environment. It cites as an example the ever-changing nature of French legislation, especially French tax legislation, 20 per cent of which changes every year.

In his evidence to the Senate hearings on 8 February 2017 the head of the Swiss bank UBS – which has 6,000 London employees and 300 in Paris – detailed the handicap for Paris-based firms in this complex regulatory environment. French banking practice’s inflexibility meant that making an employee redundant ‘takes 3 days in London, 3 months in Switzerland and 3 years in Paris’.

He explained that Brexit will only affect investment banking, which is a mere 10 per cent of staff numbers. The President of HSBC France told the Committee on 15 February 2017 that making an employee redundant in Paris in financial services cost three years salary to one in London. Decisions to relocate, according to the UBS boss, will be driven principally by the French domestic situation. Though Macron’s labour reforms have attempted to alleviate the rigidity of France’s employment laws they have only scratched the surface.

It is not merely French handicaps in financial services that help British negotiations. Britain has strong cards to play in financial services negotiations, according to the rapporteur général of the French Senate Brexit committee, Albéric de Montgolfier. He warned on the question of Europe withdrawing passporting rights from British financial institutions, for those rights work both ways. Not only would the large French banking sector suffer from not having access to the world’s second-largest financial centre (119 French firms have a London passport), but so too would French insurers who, according to de Montgolfier, have more to lose from not having access to the London market than the reverse.

The French Senate is also reserved on the question of the relocation of Euro-denominated clearing to the European continent from London. The Senate’s rapporteur général on the post-Brexit strategy for Paris as a financial centre was sceptical about the prospects of relocation, certainly in the short term. The problem was the business’s integration in a much broader London financial eco-system, the scale of London versus the continent and the fragmentation effect when relocated to the Euro area with an impact, for instance, on margin calls for companies.

France sees in the Brexit negotiations a once in a lifetime opportunity to restore Paris to its pre-First World War status as Europe’s banker. It will be played as a zero-sum game where London must lose for Paris to gain. But the struggle will be fierce. The French Senate report noted that during a working visit to the City they had learnt that eight or nine EU states were so dependent on British financial institutions that they would oppose the lifting of British passporting.

In the French Senate’s latest hearings on 19 February 2020 it is the issue of a fracturing of the 27’s unity that is a clear concern, not just on finance, but all issues of the negotiations. As several senators warned, it will be difficult to get a comprehensive agreement ‘without the unity of the 27 cracking.

The French have an interest in defending fishing, Germany cars.’ The Senate report rather incautiously revealed that according to recent testimony by the Director General of the French Treasury, equivalences will be granted to British financial institutions in certain sectors but that they will be ‘revisable and revocable as soon as Britain shows any ambition to diverge’. Similarly, the President of the Senate European Affairs committee, Jean Bizet, insisted that it was important to get European norms into any agreement. ‘For whoever controls norms also controls the market’, he announced triumphantly.

The battle will be hard and long.

This article is free to read

To unlock more articles, subscribe to get 3 months of unlimited access for just $5

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in