Lukas Degutis has narrated this article for you to listen to.

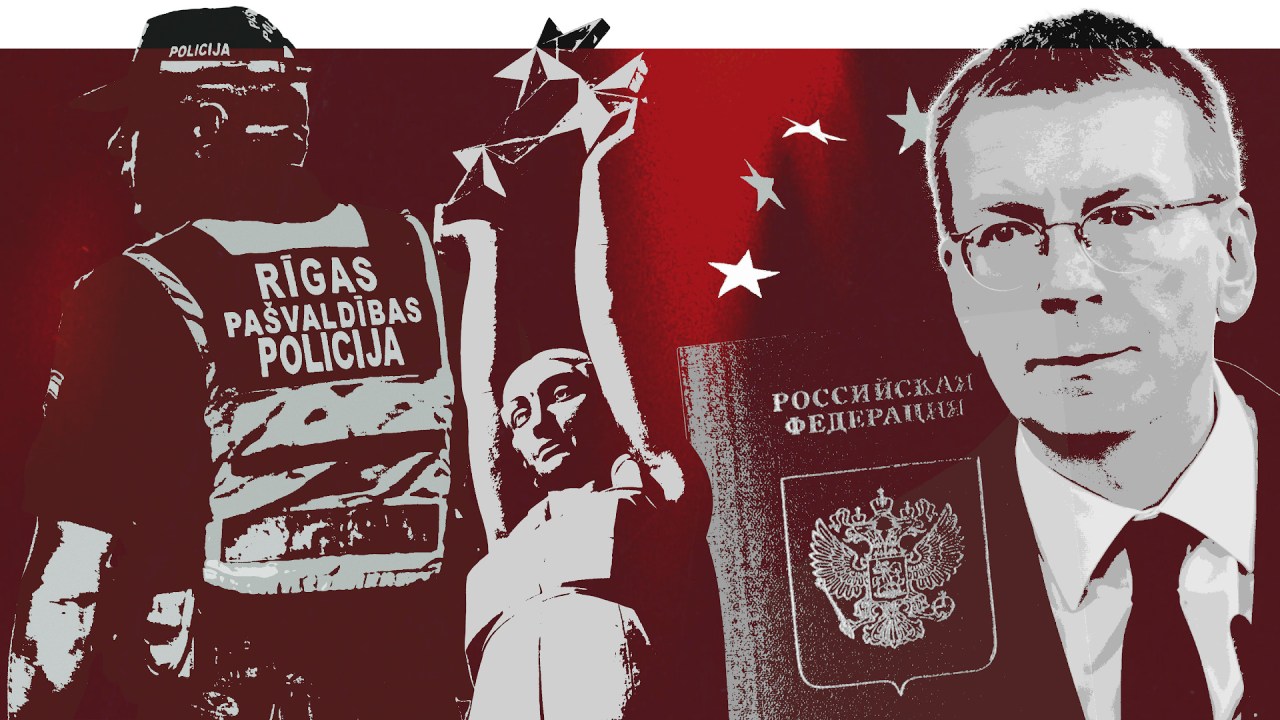

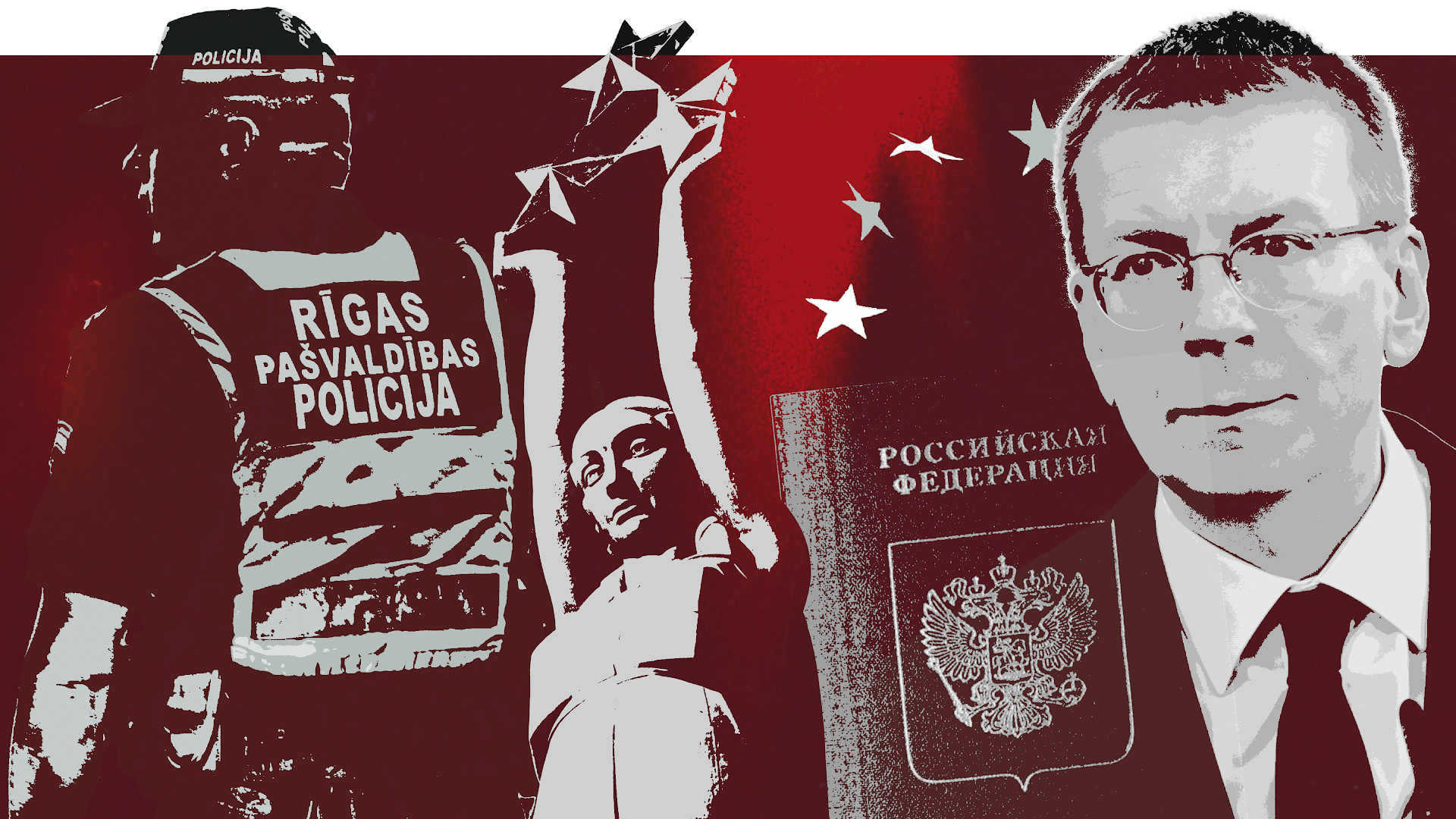

Riga, Latvia

At the age of 74, Inessa Novikova, who is ethnically Russian, was told she had to learn Latvian or she’d be deported. ‘I felt physically ill when the policy was announced,’ she tells me when we meet in an office close to Riga’s city centre.

Disagree with half of it, enjoy reading all of it

TRY A MONTH FREE

Our magazine articles are for subscribers only. Try a month of Britain’s best writing, absolutely free.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Comments

Join the debate, free for a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first month free.

UNLOCK ACCESS Try a month freeAlready a subscriber? Log in