I first became aware of the work of Marcelle Hanselaar in a mixed exhibition at the Millinery Works in Islington. All I remember now about the show, and my review, is that I said she could teach Paula Rego to suck eggs. From the mischievous energy packed into her small figurative paintings I assumed she was young enough to be Rego’s granddaughter. That was in 2003; she was pushing 60.

Born in Rotterdam in 1945, Hanselaar is essentially self-taught. She dropped out of art school in The Hague — it was the 1960s — and ran away to Amsterdam; what she learned about painting she picked up from the artists she lived with. In 1968 she drifted to India, where she lived in a cave as a sadhu, then — deciding that her ‘quest for truth had become muddled’ — she spent ten months in a Zen monastery in Japan. By the 1980s she had gravitated to London, painting lyrical abstracts and supporting herself by gardening. She was in her forties when, in 1992, the death of her disapproving mother — the woman she had always defined herself in opposition to — caused an identity crisis that triggered her first show of figurative paintings, Burying the Hatchet, remembering her mother, all horsey teeth and pearls, at her own age. ‘I had never in my life painted a face or hands.’ She did it from memory.

Fire-breathing dogs in Swiss voile aprons freely interact with – and pleasure – their human counterparts

For Hanselaar, the urge to paint is born of contradiction: a mix of fascination and disgust. She is amused and touched by self-presentation and the way it misfires: step-in corsets that cause the surplus flesh to bulge, charmeuse slips that hang like sagging skin, lipstick that cracks and smears, ‘sexy and ungainly at the same time’. Costumes, a crucial part of her pictorial armoury, are not confined to vintage lingerie: the actors in her dramas are as likely to be decked in hand-me-downs from the old masters — a ‘Trophy Wife’ in a heavy chain necklace borrowed from Cranach, a ‘Child Soldier’ in a 17th-century Dutch jerkin.

Her battery of props is equally eclectic, ranging from the domestic to the torturous, from the colander to the bed of nails. Add in the performing animals, the chimpanzees in party frocks and fire-breathing dogs in Swiss voile aprons freely interacting with — even pleasuring — their human counterparts, and the atmosphere becomes decidedly dangerous. It’s often smoky: a blackbird tries to escape from a burning cage, volcanoes throw up jets of fiery sparks, towering chimneys puff out billows of black smoke, all stoked by a febrile, uncensored imagination. ‘For a long time I worried that the subject should have authority and be acceptable. Now I’ll paint anything.’

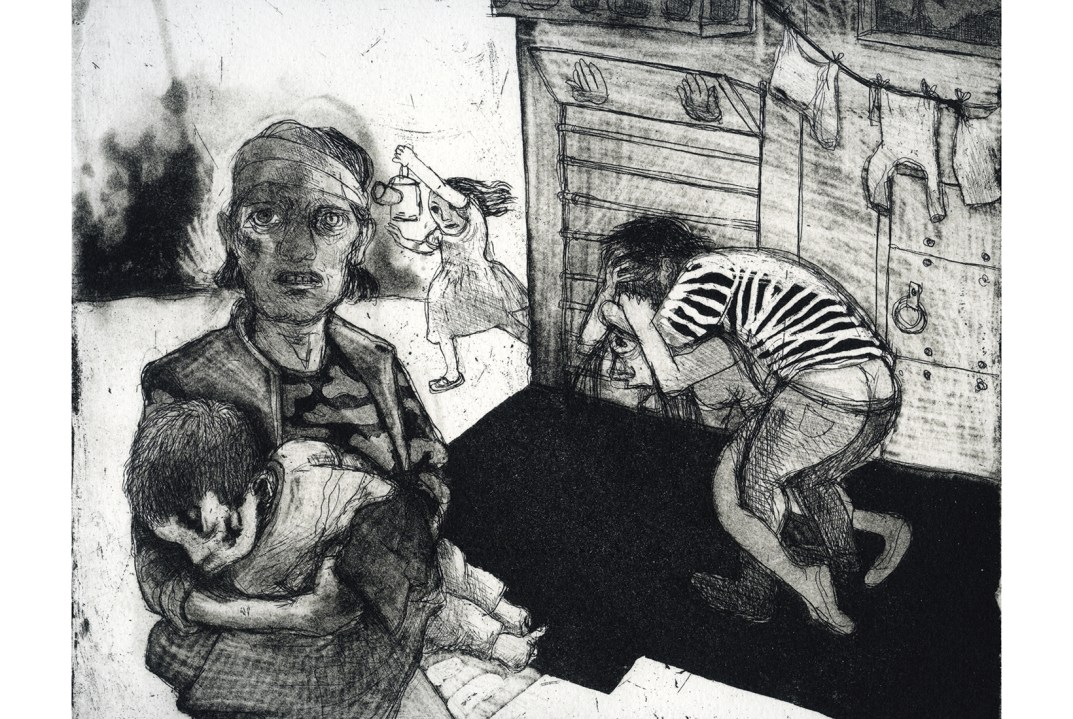

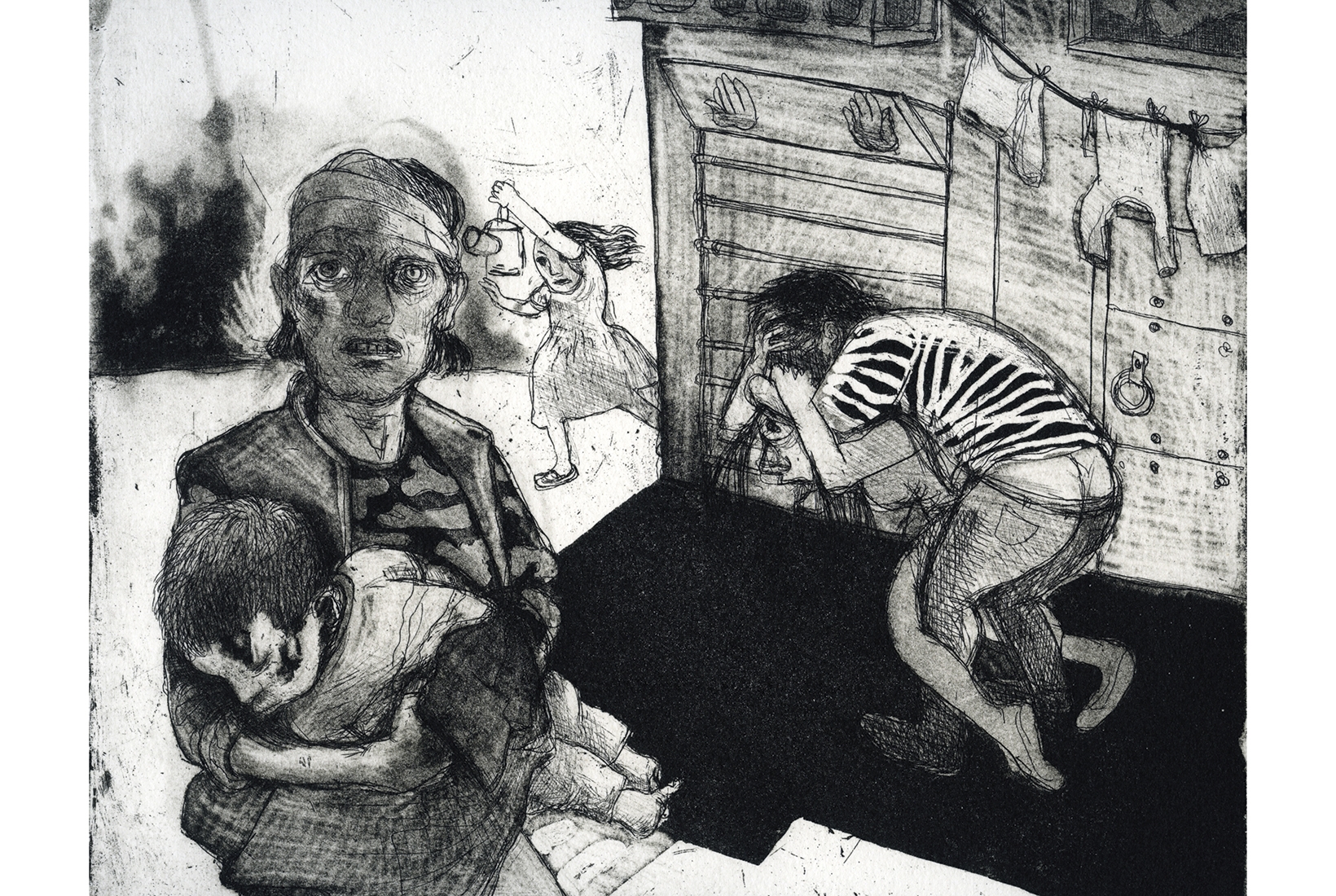

The Black Path 1’ (2020) by Marcelle Hanselaar

The problem for most figurative artists is not how to paint, but what to paint. This has never been a problem for Hanselaar. Her rush of ideas is kept reasonably in check in her paintings, but tumbles over itself in her prints. She took to etching quite late, in 1999, like a duck to water. ‘Printmaking made me more playful technically,’ she says; it also gave her fantasy free rein. Her first major print cycle, ‘La Petite Mort’ (2005), was a response to the end of an affair; a series of ‘midnight doodles’ drawn with a needle straight on to the plate, it was acquired by the British Museum.

Drawing, she finds, can be a coping mechanism. ‘A feeling you have in your own life you can put into a mise-en-scène; by mythologising it, it becomes something bigger than you.’ Five years later, in her ‘Ways of the World’ series, the private mises-en-scène erupted into public dramas — multicultural carnivals of sex and violence in which the figures of John the Baptist, Simeon the Stylite and a semi-naked sadhu are somehow caught up, observed by choruses of women in burkas and gangsters in homburgs. The fun of large-cast compositions, she says, is that ‘logic just disappears’.

In the past, Hanselaar sometimes culled images from newspapers while claiming: ‘I’m not a political person, but it doesn’t mean I have no awareness of things.’ In recent years, her awareness seems to have sharpened. The first sign was the appearance of African child soldiers in 17th-century Dutch dress in paintings in her 2013 exhibition Walking the Line — the Arab Spring was in the air — but it’s in her etchings that her growing unease about the state of the world has made itself most powerfully felt. Her 2017 print cycle ‘The Crying Game’ was a response to Otto Dix’s ‘Der Krieg’: a howl of protest at the different forms of violence human beings inflict on each other, it has been acquired for the collections of the Ashmolean, the Fitzwilliam and the Metropolitan Museum, New York. More recently, following the death of her only sister, she has returned to the personal in an elegiac series of paintings inspired by childhood memories of the North Sea. They will be shown at De Queeste Art in West Flanders in September.

In our compartmentalised art world, it’s perfectly possible for an artist to be represented in national collections and remain completely unknown to the general public. Before public galleries and international dealerships hogged all the review space, it used to be the critic’s job to worm out overlooked artists and introduce them to their readers. Now we’re left to discover them through their obituaries. But should we be kept in ignorance until they’re dead?

Comments