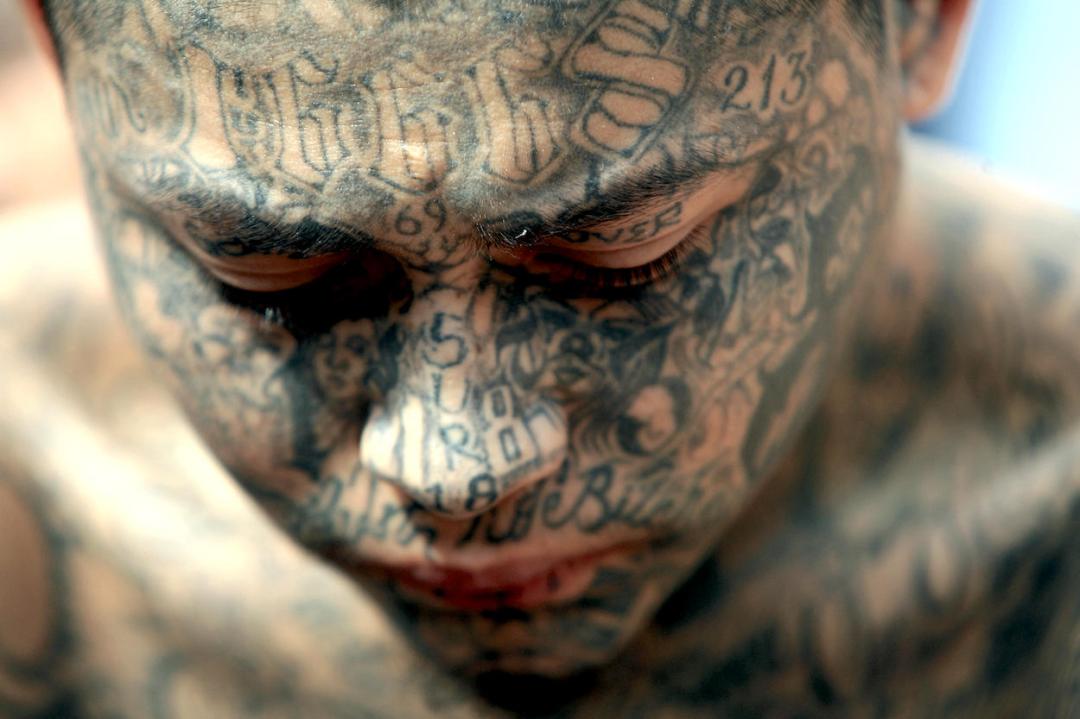

As locations go, they don’t get more humdrum than the address ‘Carrera 79B, #45D/94’. It is so anonymous it sounds encrypted. Nor, in reality, does it look like anything special: a flat roof, next to a shuttered language school, above a wall of graffiti, in a lower middle-class suburb of another Spanish speaking city. But then you notice the razorwire surrounding the nearby boutique. The armed guard outside the local bank. And you remember why this address, in the inner suburbs of Medellin Colombia, is notorious: this is where fugitive cocaine warlord Pablo Escobar was finally shot by cops in 1993 as he tried to flee across that roof.

Native American empires were bizarrely cruel – even before the Europeans arrived

Knowing that, everything looks different. Now the razorwire and the guards tell you that – despite Escobar’s execution, and Medellin’s supposed ‘recovery’ – this is still an unsafe city, surely more unsafe than anywhere in Europe. This is a city where cab-drivers point and mutter ‘peligroso, peligroso’ (dangerous, dangerous), urging you not to get out: not to mingle with the obvious addicts in the gutter, and the 13-year-old hookers outside the Jesuit church. And then you sigh and wonder why Latin America is always like this. Sketchy.

It’s a question that has vexed historians, anthropologists, criminologists, and philosophers, for decades. Something about the Spanish colonial inheritance (or Iberian: Brazil is certainly as bad) makes for peculiarly menacing cities and countries.

And they really are menacing. Just south of Colombia is Ecuador (indeed it was once part of Colombia). In the last year murders in Ecuador, already high, have almost tripled – as the country descends into an orgy of gang violence that has left the state virtually ungovernable. Meanwhile, of the top 50 cities in the world by homicide, the first seven are all Mexican (then comes New Orleans, USA). And fully 37 of the top 50 are in Latin America, with cities from Brazil, Honduras, Puerto Rico, Venezuela, Guatemala and, yes, Colombia and Ecuador, adding to the list. Astonishingly, only three cities in the list are outside the Americas, and they are all in South Africa: Cape Town, Jo’burg, Nelson Mandela Bay.

By now most people will be reaching for a uniquely American explanation, perhaps involving cocaine and fentanyl, along with the USA’s libertine approach to gun usage, leaking weapons to the south. But then you spot the anomalies. For a start, Latin America’s reputation for violence long precedes the drug trade. In 1900, a British traveller in the Americas laconically noted that however bad Haiti might be (and he thought it was bad), it did not have ‘that knife-in-your back instinct which permeates so many of the Spanish-American republics’. Some 124 years ago no one was shipping narcotics across the Rio Grande.

If it isn’t cocaine and cartels, what else might explain the ‘knife-in-your-back’ ambience? Poverty and inequality? Certainly, parts of South America are poor. Colombia has a GDP per capita of $7,000, which is pretty dismal given the potential of this vast, majestic and lavishly fertile country. But then Vietnam has a GDP per capita of just $4,000 and you can wander around Hanoi or Saigon in a way which is simply impossible in Cali or Cartagena. Likewise, most of sub-Saharan Africa is notably poorer than Latin America and easily as unequal, yet urban Latin America is more dangerous than the 95 per cent of Africa which isn’t South Africa (which complicates any racial explanation, along with any attempt to blame it all on slavery).

Could it be faith? Iberian Catholicism? Some kind of fatalism induced by the religion of guilt? This is an enticing explanation when you look at the most violent country in southeast Asia – it’s the Philippines. That’s the only ex-Spanish colony, and it is uniquely and fiercely Catholic (it was also run by the USA for a while). And Manila is perilous and ‘knife-in-your-back’ in a way unimaginable in Bangkok or Kuala Lumpur.

But here again you run into questions, because not all of Catholic Latin America is so utterly messed up: Chile is quite devout, it is also quite peaceful and prosperous. Likewise, why is Nicaragua so nightmarish, when neighbouring Costa Rica is affluent, amiable and almost European? And what exactly is El Salvador suddenly doing right (under its tough new president Nayib Bukele), that nearby Honduras apparently cannot?

At this point the puzzle begins to seem insoluble. If it isn’t religion, drugs, race, slavery, guns, politics, or the proximity of the USA, what else might possibly explain it? Could it be the simple but monumental fact of European imperialism, the original sin of the modern world, as many on the left would have us believe?

Well, no, it couldn’t be that either, because again we butt up against insuperable anomalies. For example, the British were the greatest imperialists of all – the only equivalent in human history is Rome – and we were certainly capable of wicked neglect and violence (as Ireland and India can attest) yet no British colony, with the exception of South Africa, is as dangerous as anywhere in the Latin world. Meanwhile, Britain in her imperial heyday managed to establish many of the modern world’s most magnificent cities: Sydney, Hong Kong, New York, Toronto, Singapore. And Singapore and Hong Kong are incredibly safe, with Sydney not far behind.

Is it all too difficult to solve? Maybe, but there is one final and intriguing possibility, which has been tentatively suggested in recent years. Perhaps when we look at Latin American violence we are looking at a form of legacy: an inherited memory of punishing, hallucinatory cruelty, unique to America. The Spanish empire in the Americas began, after all, with the brutality of Christopher Columbus, in Hispaniola, slaughtering and enslaving the natives: feeding them to dogs, burning them alive. At the same time, the Portuguese in Brazil were no better, arguably they were worse.

Moreover, native American empires were bizarrely cruel – even before the Europeans arrived. The Muisca here in Colombia composed special songs that they sung in chorus as they murdered their own teenage boys. In Mexico the Aztecs pulled the hearts out of living prisoners and wore their flayed skins as suits, in central America the Mayans hurled virgins down wells and played ballgames that ended in head-chopping,

Then there’s the Moche civilisation of northern Peru (100 to 700 AD) which was insanely depraved and bloodthirsty – to an extent it is difficult to comprehend. Moche aristocrats used to cut off their own noses, lips, feet, as a sign of nobility. Moche women probably had sex with pumas in special rooms, other Moche apparently masturbated and sexually penetrated partly defleshed corpses.

During their most intense rituals entire Moche clans, cloistered in darkened pyramids, would engage in sodomy and fellatio in orgiastic celebration even as they watched their siblings and children being slowly bled to death in the centre of the chamber, all to honour a strange tarantula god (also known as the decapitator god). What’s more, most of this – as in so many pre-Colombian civilisations – apparently happened in a haze of hallucinogenic drugs. The favoured drug of the Moche was called ulluchu (we are still not certain what it was); other pre-Columbian civilisations eagerly consumed peyote, yopo, san pedro, ayahuasca, coca, mapacho, and so on.

Is this, then, the answer to the paradox of Latin violence? Is it some kind of cultural inheritance of drugged-up violence, descending the centuries and the millennia? An enormous epigenetic curse? It is tempting to say Si, but of course there is no proof.

However, even if we can’t firmly explain the Great American Violence, one man seemed to predict it, and that man was Simon Bolivar, the revered liberator of Latin America. In 1830, as he was dying of tuberculosis and raving in his genius, not far from Medellin, Bolivar wrote a letter to the first president of Ecuador, where he made six famous statements about his continent of revolution, South America:

1. America is ungovernable;

2. Those who serve a revolution plough the sea;

3. The only thing you can do in America is leave it;

4. This land will fall inevitably into the hands of the unbridled masses and then pass almost imperceptibly into the hands of petty tyrants, of all colours and races;

5. Once we have been eaten alive by crime and extinguished by utter ferocity, even the Europeans will not regard us as worth conquering;

6. If it is possible for any part of the world to revert to primitive chaos, it will be America in her final hour.

As we look at the gunshot citizens of Quito, and the schoolgirl hookers by the churches of Colombia, it is hard not to link to Bolivar’s sixth and darkest prediction. And if that in turn leads to a terminus of despair, remember that Bolivar also believed, throughout his life, that South America would eventually achieve great and wonderful things. It’s just a pity he died before he could tell us how this might happen.

This article is free to read

To unlock more articles, subscribe to get 3 months of unlimited access for just $5

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in