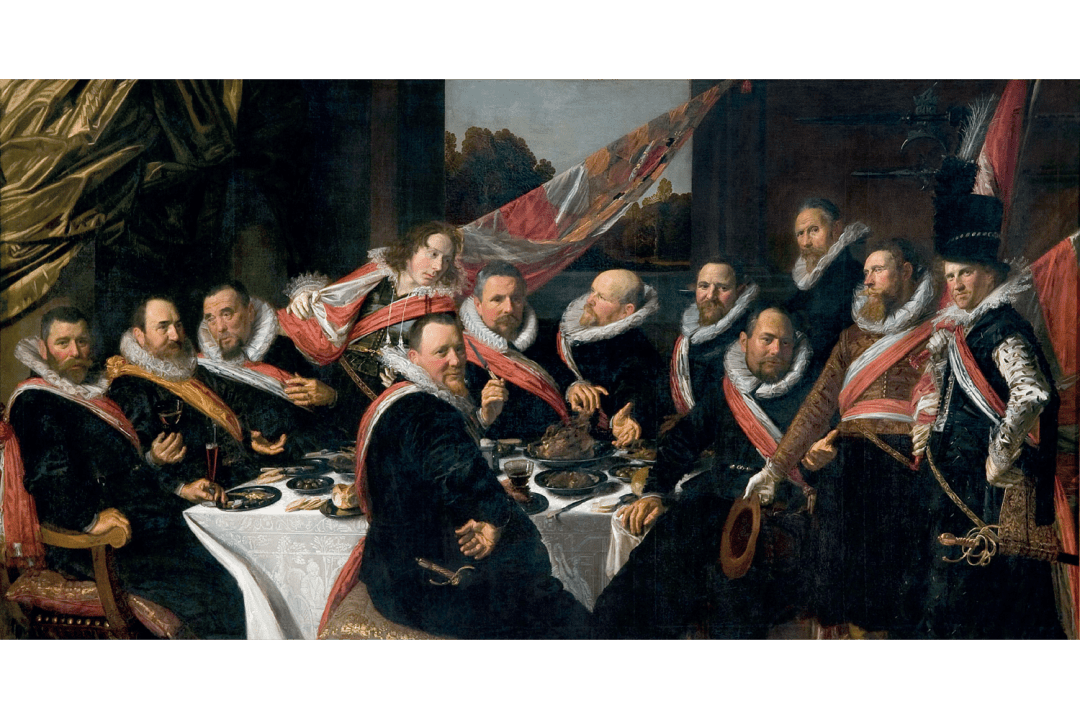

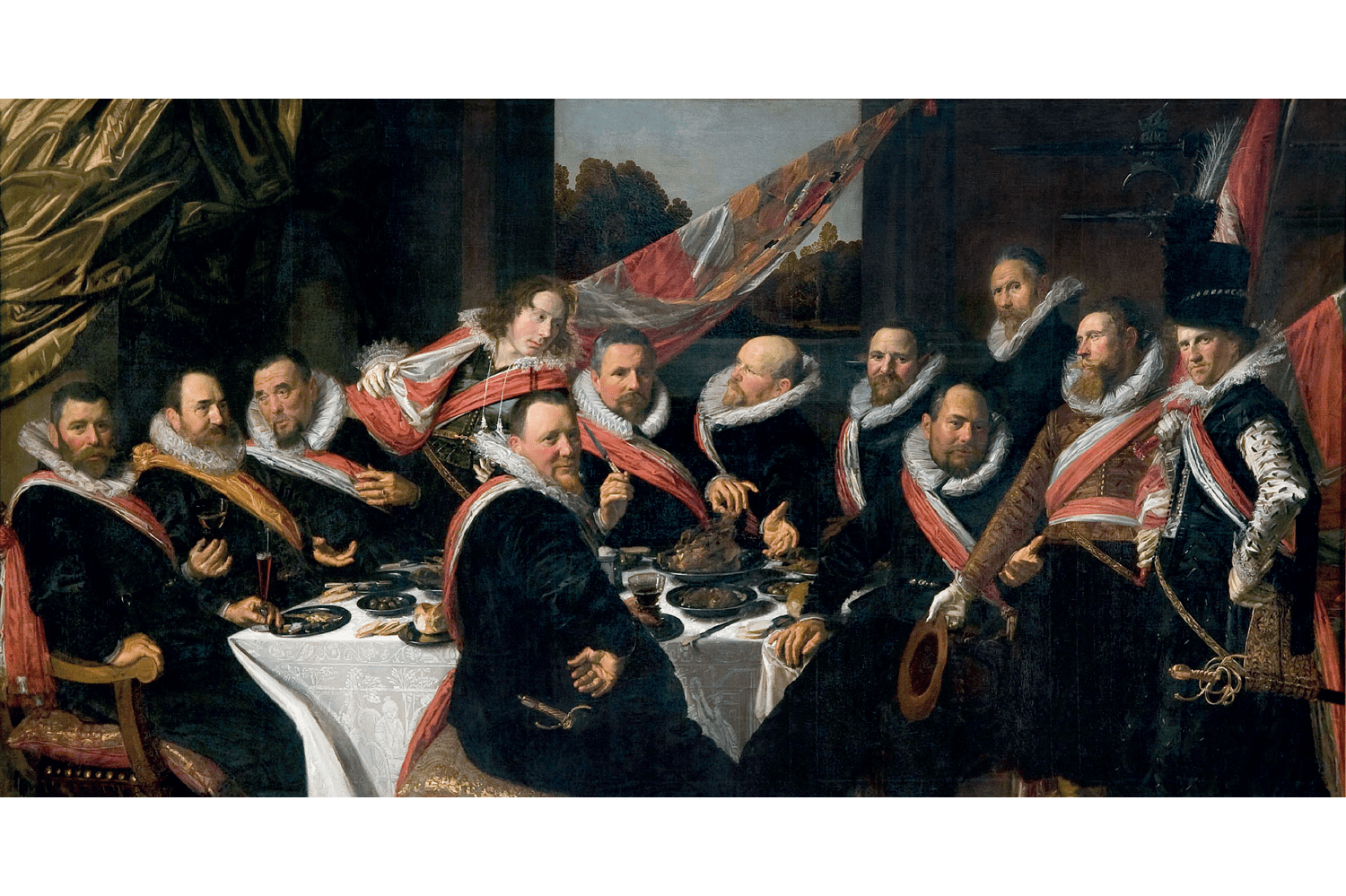

Who was Frans Hals? We know very little about him. He was baptised in either 1582 or 1583 in Antwerp. He died in 1666 at the age of 83 or 84. Approximately 220 works survive. One discredited narrative claimed Hals was a drunk – an inference probably based on his subject matter. There are several depictions of drinkers. On the other hand, there is his evident industry. Two streets in Haarlem, where he lived his entire life, have been identified, but not the actual houses. He was buried in St Bavo’s church in the Grote Markt, which was originally Catholic but became Protestant. There are two commemorative slabs next to each other in the chancel floor competing for authenticity. Which is appropriate, because there are two Frans Hals – the traditionalist and the innovator. They co-exist.

There are two Frans Hals – the traditionalist and the innovator. They co-exist

The Frans Hals revered (and sometimes lovingly, painstakingly copied) by Whistler, John Singer Sargent, Lovis Corinth, James Ensor and Van Gogh is a spontaneous, apparently improvisatory painter. Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo: ‘What struck me most on seeing the old Dutch pictures again is that most of them were painted quickly, that these great masters, such as a Frans Hals, a Rembrandt, a Ruysdael and so many others – dashed off a thing from the first stroke and did not retouch it so very much…’ You can see this painter’s signature style – almost a kind of unhesitating writing, full-tilt, semi-automatic – in the Rijksmuseum’s ‘Militia Man’ (c.1629) also known as ‘Merry Drinker’ (see below). His left radically foreshortened arm is holding out a glass to the viewer. The beard and moustache are wind-swept and warped like a coastal thorn tree, detailed without being pedantic, precise yet with an air of being tossed off.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in