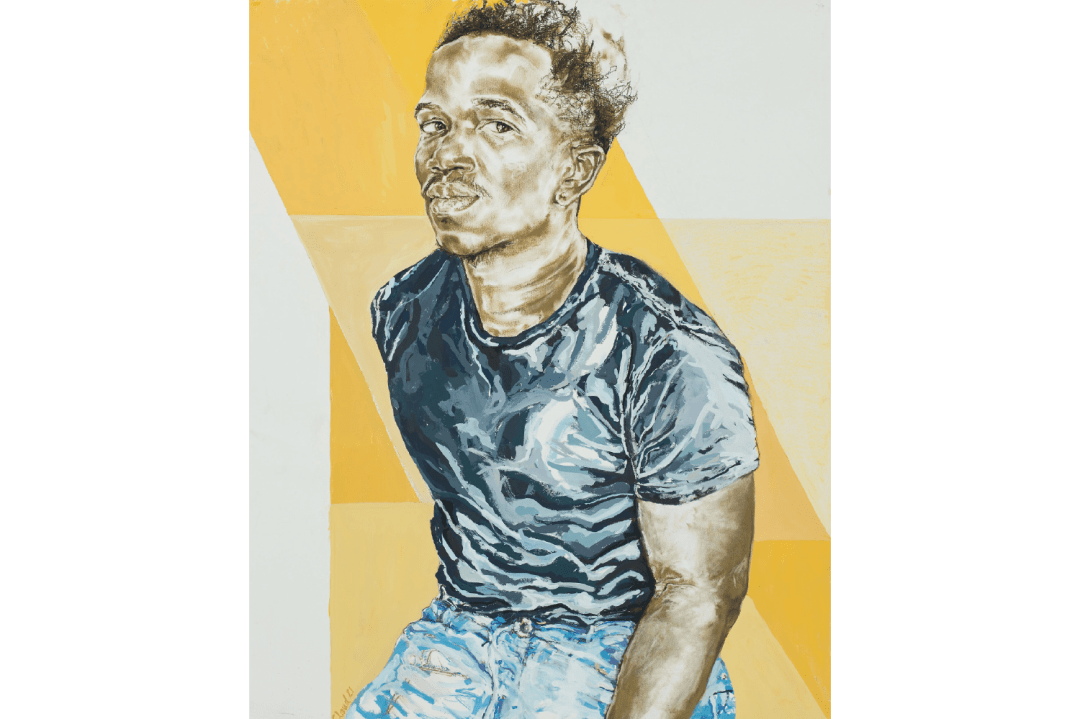

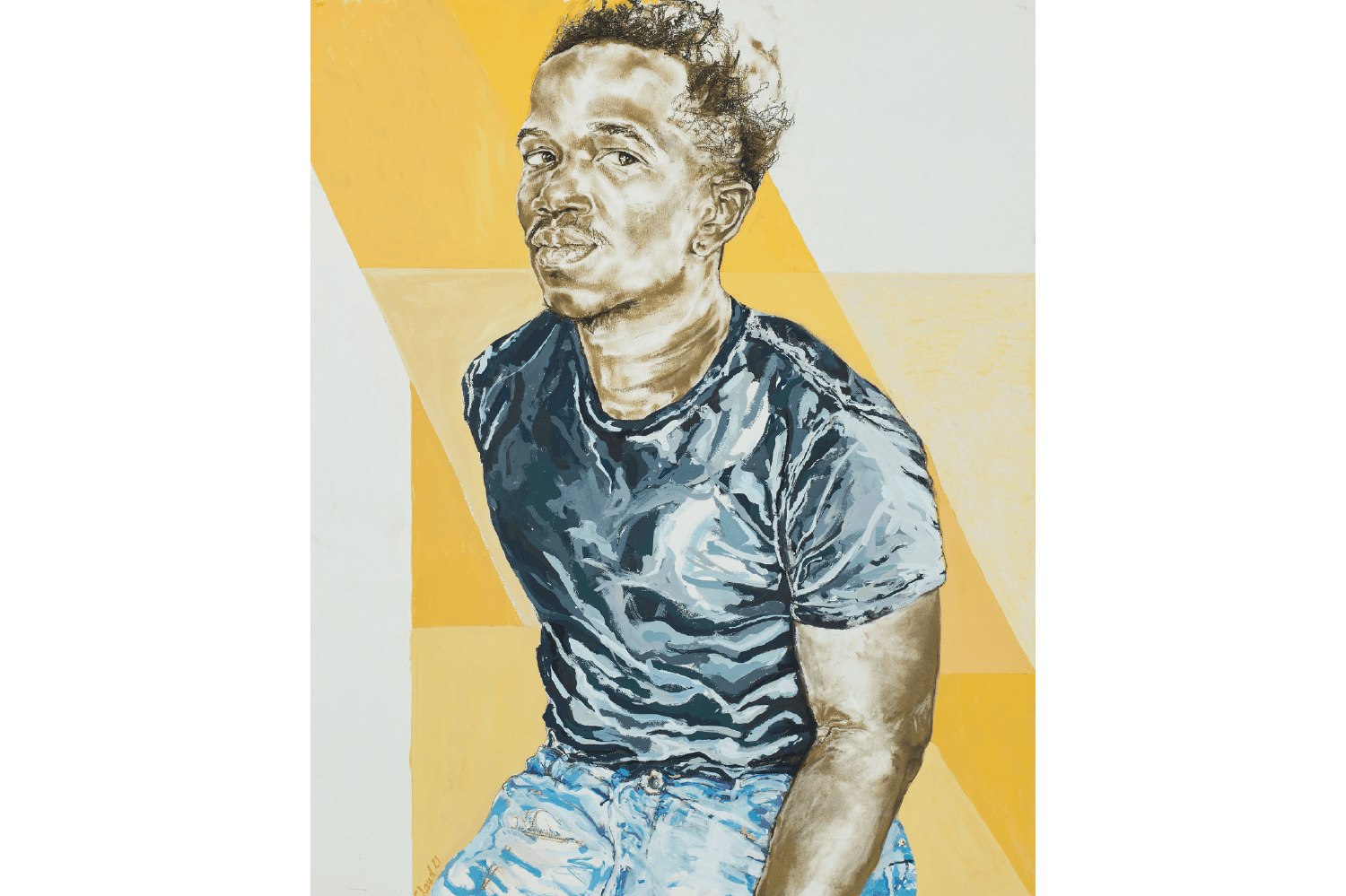

While looking at Claudette Johnson’s splendid exhibition Presence at the Courtauld Gallery, I kept trying to pin down an elusive connection. Her works are large drawings (sometimes very large – one reclining figure is more than two-and-a-half metres wide), and each one zooms in on a single figure seen in close-up, often larger than life-size. They reminded me of something, but for a while I couldn’t place it. About halfway round I got it. They look a little like fragments from the cartoons Renaissance masters made as templates for painting. These, too, tend to concentrate on the human body on a monumental scale.

Those who dedicate themselves to drawing and work from live models are scarce. Johnson does both

Claudette Johnson is female and she is black, neither of which are as unusual in the art world as they were when she began her career in the early 1980s (one respect in which the world has become better since then). But she is a highly unusual artist for another reason. Those who dedicate themselves to drawing and work from live models are scarce nowadays, and Johnson does both.

There are quite a few artists around who depict what David Hockney likes to call the ‘visible world’ (sometimes described as ‘figurative’), but these days they are more likely to work either from photographs or imagination. When we met, Johnson told me why, despite the difficulties, she prefers to sit and draw in front of a living, breathing person. In fact, she does this partly because of the difficulties. Working from life, she explained, is not only more challenging but also more embarrassing (which was one of the reasons why Francis Bacon used photographs rather than living sitters). ‘When I’ve worked with someone I didn’t know particularly well,’ she said, ‘there’s always an initial period of awkwardness.’

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in