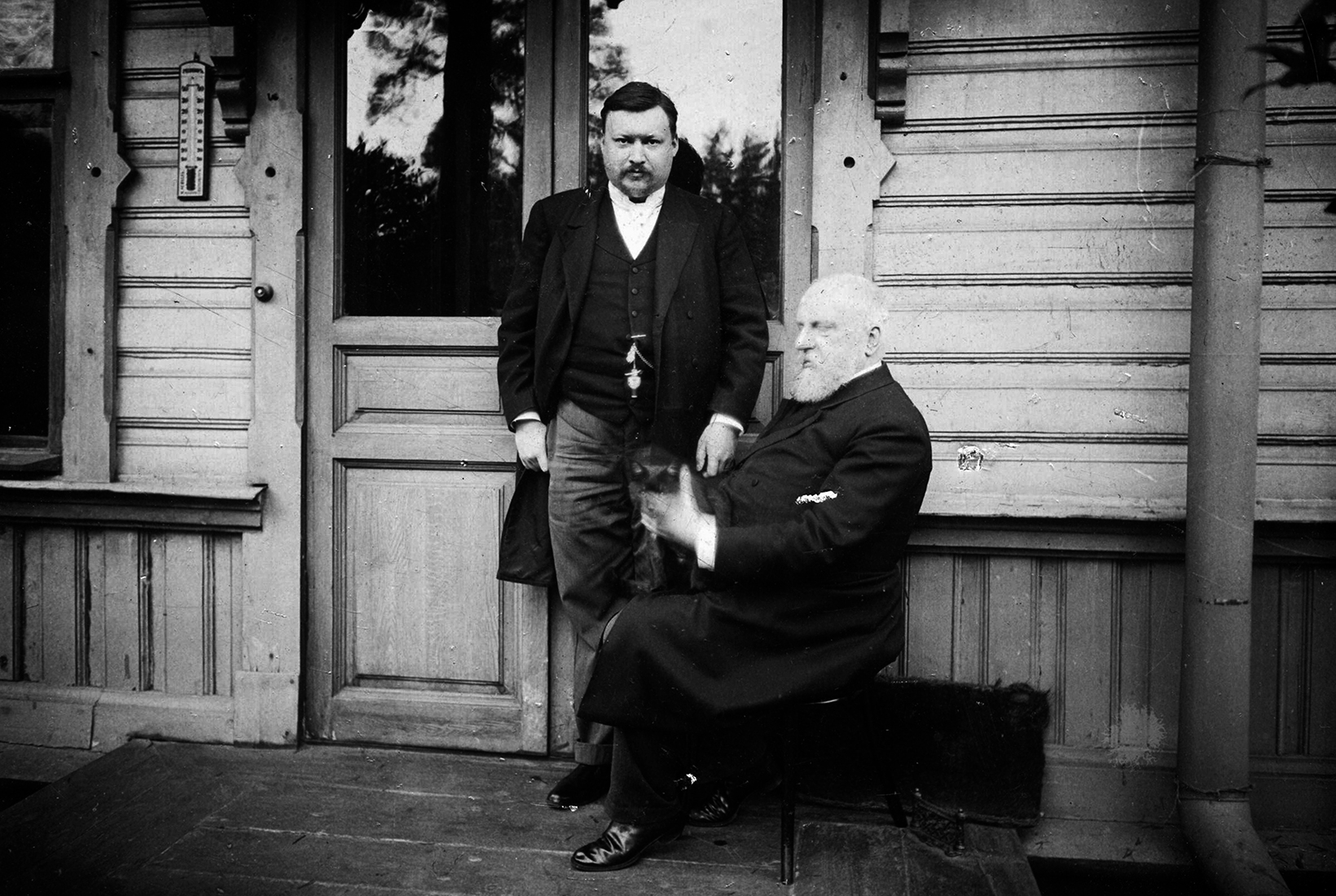

Anyone who invited the Russian composer Mily Balakirev to dinner had to be jolly careful about the fish they served. How had it died? Balakirev — mentor of Mussorgsky and Rimsky-Korsakov and regarded as the founder of the Russian nationalist school of music — would want to know. If the fish had perished on a hook, then he wouldn’t touch it. But if it had been clubbed on the head, fine.

The many eccentricities of Balakirev (1837–1910) were regarded with amusement, horror and dismay by his contemporaries. Though, to be fair, the fish thing wasn’t a mad obsession of his own. Formerly an atheist, in his thirties he converted to an ultra-strict Russian Orthodox sect with firm views on the proper way to kill fish. Unfortunately this wasn’t the only subject on which it was inflexible. It was anti-Semitic even by the standards of Tsarist Russia, which is saying something. And Balakirev outdid even his own clergy with his ranting about ‘Christ-killers’. So, no Jews at the dinner party — or anyone the composer suspected of being Jewish simply because they disagreed with his musical opinions.

That last detail is significant. Balakirev suffered from paranoia exacerbated by a midlife nervous breakdown from which he never really recovered. It was a wretched blight on an astonishing career. He studied mathematics at university, not music, but eventually acquired such a mastery of musical theory that in 1881 he was offered the directorship of the Moscow Conservatory. He turned it down, preferring his own Free School where composers were encouraged to develop an ‘oriental’ style.

Nicholas Walker has recorded a Balakirev cycle that has to be heard to be believed

Balakirev loved the ‘savage tribes’ of the Caucasus and once spent five weeks there in a monastery of fire-worshippers. He was the first major Russian composer to borrow heavily from ethnic traditions and, in doing so, changed the course of his country’s musical history.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in