Britain may look like it’s back to normal after the lockdowns but one alarming trend that emerged in 2020 is very much still with us: people dying at home, who would once have been seen in hospital. This is called ‘excess’ at-home deaths; a number very energetically reported when deaths related to Covid — but not so closely followed for the thousands unrelated deaths. So what’s going on?

This year so far some 13,000 people more than average died at home in England and Wales. In hospitals though it’s 7,200 below average and there have been 3,649 fewer in care homes too. In Scotland there have been over 7,000 excess deaths at home, but only 1,000 in hospitals and in care homes there were 1,320 less than expected. This could be a sign of Illnesses not being diagnosed through the normal health channels. Doctors are worried.

In the week to 17 June (the most recent data), deaths at home were 30 per cent above five-year average while deaths in hospitals just 10 per cent above average. Some 715 more people died than had been expected to. The Covid wave we’re in now — caused by the more transmissible BA.4 and BA.5 sub variants — has pushed hospitalisations up and with them excess hospital deaths too. But proportionally these deaths are still far smaller than those at home — 29 per cent vs 10 per cent in hospitals and 16 per cent in care homes. For the first 15 weeks of this year there were no excess hospital deaths at all.

The lack of excess deaths in hospitals and care homes at the start of the year can to some extent be explained by how excess deaths are calculated. The five-year average statisticians use now includes 2021 (though 2020 is left out). In January and February last year Covid deaths had just peaked. So for the equivalent weeks this year the average is pushed up. But the ONS say this effect stops by the end of February. And it doesn’t explain the increase in at home deaths either.

The change began during the pandemic. In 2020, deaths at home were a third higher than the previous four years (166,576 vs 126,411). At the time the ONS said the excess deaths ‘were people who, in a non-pandemic year, may have typically died elsewhere such as in hospital’. To June last year private homes were the only setting with deaths consistently above the pre-pandemic average in every single month. That trend has continued.

What are people dying of? The largest killer so far this year has been Alzheimer’s and dementia, followed by heart disease. Together these causes have killed nearly four times as many people as Covid has this year. Covid distorts the figures too: many deaths with the virus listed as the main cause occurred where other diseases contribute. So the real gap might be even bigger. The population is ageing — census results published this week show one in five of us are over-65. The low birth rate means that proportion will only go up, so each year the natural death risk goes up too. But diseases are becoming more treatable. Shouldn’t excess deaths be coming down?

Wherever you look in the country you’ll find concerning mortality data. Figures from Scotland this week found infant deaths at their highest in a decade: 3.9 babies died for every thousand born. A 26 per cent increase on the year before. The deaths at home trend persists north of the border too — up 36 per cent on the pre-pandemic level.

Might the rise in at-home deaths be linked to the Covid vaccines? A paper by BMJ Editor Peter Doshi is doing the rounds saying that in trials the jab’s side effects hospitalised more than the virus. But the data wasn’t actually that clear cut. Sir David Speigelhalter, a statistician from Cambridge, points out that the study ‘only considers Covid hospitalisation during the trials themselves, which covered only around two months at a time of low Covid. The true benefit of vaccines extend far beyond this period, so the harm/benefit comparison used in this study seems entirely inappropriate’. He doesn’t think the Doshi paper will pass peer review.

But why then is all this happening? I spoke to one doctor, Charles Levinson, who runs a private visiting GP service from Harley Street, given a stark assessment: he links the deaths to the drop of appointments in lockdown (something Sajid Javid has highlighted).

Here’s Dr Levinson:

Every slight bump or uptick in the Covid numbers demands endless column inches, but there is total silence from so many on these damning statistics. It’s clear that over the pandemic thousands and thousands of people were unable or unwilling to seek medical advice. Leading to severe complications and — far too often — death. The nature of these diseases means I fear we are not anywhere near to discovering the full extent of this crisis — that is reflected in the numbers which continue to stagger me.

Dr Levinson’s company, Doctorcall, provides private GPs. He says his staff talk of ‘terrified’ patients:

One example that will stay with me forever was an elderly man who was attended to by one of our visiting doctors. The man had just suffered a heart attack, but was so terrified of potentially catching the virus that he refused to go to hospital. The medic followed all the correct procedures and was left disturbed by the incident.

A third of appointments are still over the phone — a figure that is gradually decreasing over time (see below)

Nearly 60 per cent of GPs work a three-day week. And it recently emerged one in four GP posts will be vacant by the end of the decade. There is a resourcing crisis in general practice – over 2,000 of Britain’s 9,000 GP surgeries are using locums – and things could get significantly worse.

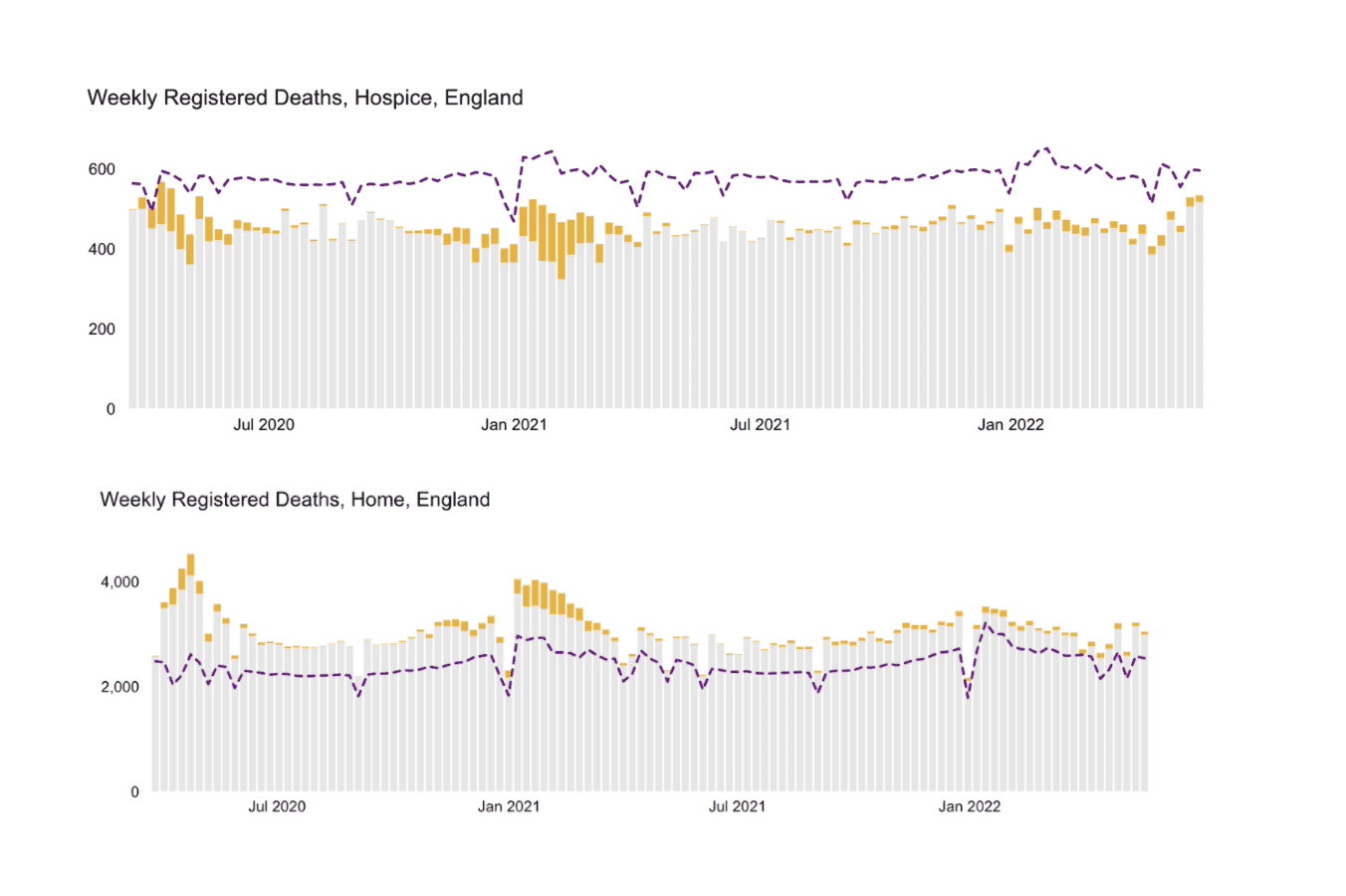

If this were a stirring of a new pathogen, there would be plenty of attention – and questions asked in Parliament about the thousands of deaths. The government should be aware of what’s going on. Since early on in the pandemic the little-known Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, one of the bodies brought in to replace Public Health England, has been running an excess mortality dashboard for England. It includes some fascinating graphs. The two below look at ‘expected’ deaths (the purple line) against actual. Throughout the pandemic there have been less hospice deaths than expected – but far more in homes. Government has the data, is it doing anything with it?

The figures show no sign of reversing. As society continues to recover from restrictions and fear, the health service seems stuck. Dr Levinson is clear where the blame lies: ‘It’s a terrible legacy of lockdown — one of many. It must never happen again.’ But perhaps how we view hospitals has simply changed.

Perhaps this change in where we die reflects a societal shift in UK preferences. Doctors talk of encouraging those at the end of their lives to pass away at home to avoid additional pressure on hospitals at the height of the pandemic. Many rightly feared a hospital death would be a lonely one with draconian and unnecessary restrictions on visitors. That can’t explain the full surge in at-home deaths though, a proper investigation is surely needed.

This article is free to read

To unlock more articles, subscribe to get 3 months of unlimited access for just $5

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in