If you read only the title of Charlie Taverner’s book Street Food you could be forgiven for assuming it was an exploration of the stalls that line the trendier streets of our cities, offering bibimbap and bao, jerk chicken and jian bing. But the author’s focus predates brightly coloured gazebo hoardings and polystyrene packaging and looks instead at the working lives of the itinerant traders who populated London before 1900, touting everything from oysters to milk, and what their work meant for a changing capital city.

By placing these vendors at the centre of the story rather than as faintly comic support acts, Tavener provides something that goes beyond individual characters. As he puts it: ‘The history of hawkers offers a ground-level, centuries-long view on London’s expansion.’

Dismissed as nefarious characters, hucksters and fishwives became bywords for scurrilous behaviour

These street sellers occupied a unique place in society. Though their work was unregulated and usually poorly remunerated, they nevertheless drove London’s social and economic change. Tavener writes:

Hawkers help us reconstruct London’s story around the basics of metropolitan life: inter-actions on the street, the exchange of essentials and the struggle with material conditions, much of which took place outside formal institutions and fixed sites and beyond the grasp of governors and magistrates.

Comprehensive regulation came later with pitch-assigned covered markets, and ultimately the advent of supermarkets. But for 300 years this ‘informal retail’ was the principal provider of fresh produce to neighbourhoods not served by wholesale markets.

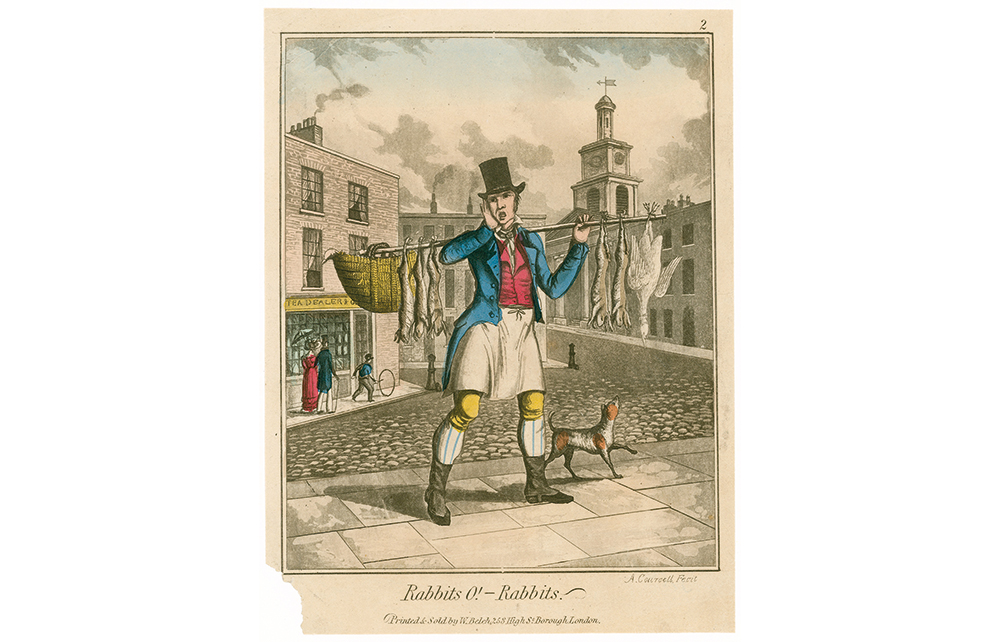

It was that combination of poverty, informality and independence that placed the traders in legal limbo and on the edge of propriety, which in turn led to their vilification, reducing them to little more than public nuisances. For centuries they were captured pejoratively in song, art and literature and dismissed as nefarious characters, hucksters and fishwives becoming bywords for scurrilous behaviour.

This genre of representation, known collectively as ‘The Cries of London’, has much to offer the historian; but it can also descend into a sort of commedia dell’arte of players, showing only archetypes and caricatures. Take the fishwife, ‘an essentially comic creation, whose behaviour poked and prodded the conventions of early modern society’. Tavener digs deeper, unpicking the character: ‘Running against expectations of gender and sexuality, the fishwife embodied the anxieties of a strongly patriarchal society about women working and moving through the city independently.’

His central argument is that the vendors constituted ‘a distinctive form of urban existence that persisted for several centuries, a street-based experience of working people who scraped, slogged and hustled to get by’. Taverner is an academic, and thebook is an expansion of his doctoral thesis, bursting with knowledge and learning. It is a meticulous chronicling of the ‘heyday’ of street selling, from 1600-1900, something which hasn’t previously been done. So if on occasion it’s repetitive or gets bogged down in detail, it’s understandable, being a significant piece of research.

Gathering information from court records and the minutes of local authorities, Tavener puts names to faces. From such primary material, he has identified 858 individual hawkers and 443 acts of street selling. That’s not to say the book is a slog. The writing is accessible and enjoyable, and the sketches of these streetscapes and their inhabitants, and ‘the tension of living in a great metropolis’, makes for vibrant, engaging reading. It is a world reconstructed with real humanity and warmth: ‘We have to listen to street sellers’ cries and rows as they make a sale, sneak a glance at the food inside their baskets, and follow them back to their neighbourhoods and homes.’

The result is a rounded picture of a previously misunderstood world. Taverner affords these characters dignity – ‘hawking was not rock bottom. It was a way to stay above water’ – and draws links between their precarious work and today’s gig economy, devoid of rights and stability. Street Food provides an insight into a different London – an older one, of course, but also a more complicated one, that illustrates the diversity of those living and working there. For anyone interested in the economics of food or the capital’s history, this is a fascinating book.

Comments