Dear Education Secretary,

I am worried your time in office will destroy the huge gains made over the last decade and a half in helping disadvantaged children across England. I don’t know if you are being ideologically blind and therefore ignoring the obvious negative impact of your decisions – or perhaps you just don’t understand the harm your changes will cause. I am hoping it is the latter and I am writing to offer my advice and help so that you might see that the road you are taking will have catastrophic consequences for the poor in this country.

Cutting funding to schools just before the GCSE exams

I say this as a headteacher who has chosen not to offer Latin to our pupils at Michaela Community School in Wembley, North London. Why would you cancel the grant that allows disadvantaged children across the country, including very deprived areas in the north, to access Latin GCSE? Why would you cut their grant, upon which these schools entirely depend to employ Latin teachers, just months before these children take their GCSE exams? Presumably you could have waited until the summer, instead of pulling the rug from under countless heads, who are doing their utmost to give their disadvantaged kids a chance at competing with the kids at Eton?

I cannot for the life of me, understand it. What was the problem you were trying to solve?

Freedom over the curriculum

Some headteachers and their senior teams, consulting with their staff, and supported by their governors, chose Latin. Others did not. Schools have different intakes across the country. Allowing us as school leaders the freedom to do what is best for our children is not just a sign of respect and trust for us as teachers, recognising that you, as a politician, might not know as much as we do about what is best for our children whom we see daily and whom you have never met. It also shows respect for their families, who are able to choose the school that is right for their child. Do you really believe you know better than all of us?

Your curriculum changes will cost schools time and money

Clearly there needs to be a broad academic core for all children. But a rigid national curriculum that dictates adherence to a robotic, turgid and monotonous programme of learning that prevents headteachers from giving their children a bespoke offer tailored to the needs of their pupils, is quite frankly, horrifying. Anyone in teaching who has an entrepreneurial spirit, who enjoys thinking creatively about how best to address the needs of their pupils, will be driven out of the profession. Not to mention how standards will drop! High standards depend in part on the dynamism of teachers. Why would you want to kill our creativity?

Then there is the cost. Your curriculum changes will cost schools time and money. Do you have any idea of the work required from teachers and school leaders to change their curriculum? You will force heads to divert precious resources from helping struggling families to fulfil a bureaucratic whim coming from Whitehall. Why are you changing things? What is the problem you are trying to solve?

International Tables

I realise the Conservatives are your opposition. To be clear, I am not a member of the Conservative party. Nor did I vote for them in the last election. I am a floating voter, as I believe everyone should be, but I digress.

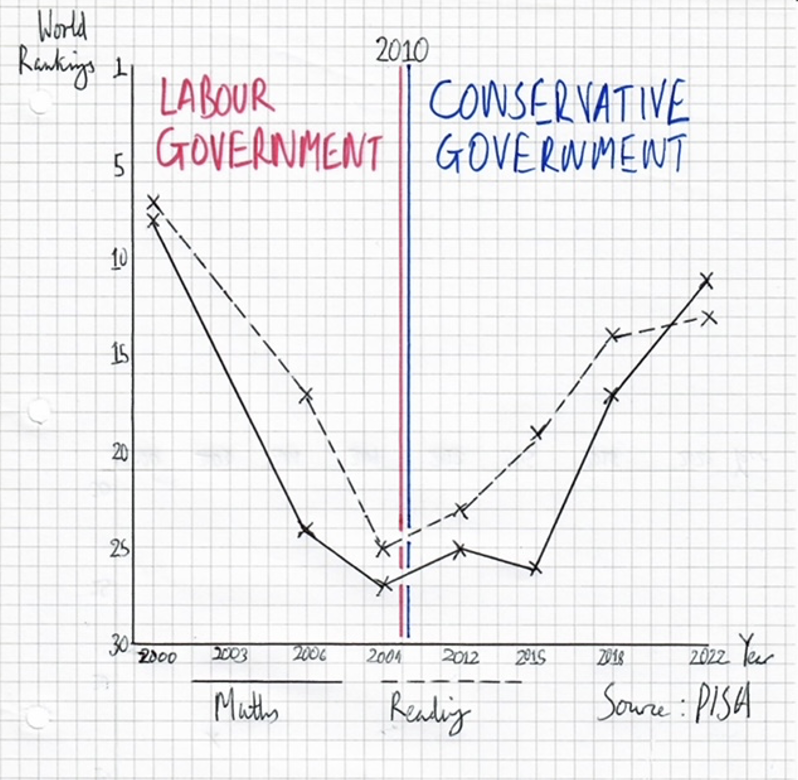

You can see in the graph above the good that the Conservatives have done for education. The country is currently facing a number of huge problems, as the government has told us. The economy is flatlining. The NHS has huge challenges. Courts are backlogged. Prisons are bursting. There’s a war in Europe.

Amongst all the gloom, there is one bright spark: England’s schools

But amongst all the gloom, there is one bright spark: England’s schools. They have risen up the international rankings over the last decade and have become a subject of international interest. As one small example, at Michaela, we get over 800 visitors every year, often teachers and school leaders (including many international ones), all interested in how England has massively improved opportunities for children.

Wales and Scotland have either fallen behind or remained more or less the same in the international league tables, whereas England, between 2009 and 2022, rose in the OECD Pisa school rankings from 21st in the world for Maths to 7th. The PIRLS league tables for reading now rate England as the top country in the western world.

As the new Education Secretary, you might want to leap at the chance to learn from the success of England’s schools, and then advise your colleagues on how to improve other public services. But instead, you are spending precious energy, political capital and parliamentary time on destroying the reforms that led to this success. You want to take away the freedoms that academies have, one of the major planks of the international success that other countries can only admire. Again, your decision isn’t solving a problem; it is creating huge problems for schools.

Hiring of teachers without qualified teacher status

Why would you want to prevent schools from hiring graduates and then getting them trained through a variety of routes? I have lost count of the number of unqualified teachers we have hired at Michaela who have been trained with us and then, after some years, have gone on to middle and senior roles at other schools, taking the expertise they have gained from working with us. My current Head of Year 11 is one such teacher. He used to be in the army and is doing a superb job with the kids. With your new rules, I would never have been able to hire him. Again, what is the problem you are trying to solve? And why would you do this when nationally we have a teacher shortage and a recruitment problem? We need as many routes into the profession as possible.

Uniform

Another freedom that it seems you want to snatch away is allowing schools to have the highest expectations of our children in terms of dress code. Do you assume that schools don’t care about their poor kids and simply enjoy branded uniform items for the sake of it? If so, you are taking a very dim view of teachers. Teachers and school leaders love their children and do not wish to make their lives difficult. If you do not understand why we do what we do, it might make sense to ask us.

Have you ever asked a school leader why we have branded items? Have you ever asked England’s football team why they wear the same shirt? It is hard to know who to pass to on the football field, if everyone dresses differently.

I know you have spoken about the importance of children feeling as if they ‘belong’, for attendance to improve. You have rightly pointed to attendance as being a national issue since the pandemic. For children to feel as if they belong, they must have something to belong to: their school must be allowed to brand their uniform items. Without this, a sense of team is impossible, and the most disadvantaged will suffer.

Schools also use branded ties to denote prefects, future leaders, sports captains and the like. Would you really want to prevent schools the opportunity of inspiring their children with leadership roles? The blazer is how one knows the difference between schools, like when England is playing Colombia – they wear shirts representing their countries. The same thing goes for the bag, which sits on their backs; from far away, teachers can see whether their kids are safely crossing the road and behaving when getting on the buses. The sweater similarly, if one says ‘blue’ or ‘grey’, the hues and materials are so different, you suddenly have a bunch of kids who look like they attend different schools, undermining your aim of increasing a sense of belonging in kids.

It seems like you don’t ask these questions

Perhaps this is not obvious to those who are not in teaching. That is why it is so important for you to ask us practitioners; in particular, to ask the more successful schools why we do what we do.

A rule that requires branded trousers may not seem obvious to the non-teacher, but allow me to explain. In the inner-city and even beyond, boys who are vulnerable to the street, begin by pulling their trousers down their backsides. Having trousers that cannot be pulled down, but that can be recognised easily by a cleverly positioned logo so that teachers can hold their standards high with the kids, means that vulnerable boys in the inner-city are more likely to feel as if they belong to their school. It also ensures girls are not pressured into shortening their skirts or tightening their trousers. This limits opportunities for sexual exploitation and keeps both boys and girls safe from harm. If kids at private schools have this protection, so should poor kids in the inner city.

Were you to probe more into the issues that schools face, you might discover that schools collect in hundreds of second-hand uniform items, dry-clean them, and sell them at a fraction of their original cost to families, including providing some families in dire need with items at no cost at all. But it seems like you don’t ask these questions, and for the life of me, I don’t understand why. Again, I would ask, what is the problem you are trying to solve?

Freedoms on pay for academies

I am not sure if you realise, but lots of academies have used their freedoms to pay their staff more than the national pay scales. Your bill could stop them doing that. Academies can pay teachers more by making back office efficiencies and thinking outside the box. You have said that taxing private schools will help the state sector. You have also said that teachers aren’t going to get a pay cut, but this bill risks doing exactly that.

Again, I am wondering what problem you are trying to solve? One of the very real problems that needs solving is recruitment and retention. So many schools cannot find teachers for their classrooms. Some schools need support in establishing robust behaviour systems and, for that, they need the ability to retain their excellent staff. That might be what you should focus on, instead of creating conditions which will threaten retention of teachers even more.

An invitation

I worry that you don’t seem very interested in doing the research or looking at the evidence. I note that you refused to congratulate Michaela when asked to do so in the House of Commons, on achieving the highest Progress 8 in the country three years in a row – something never done before. I have no idea why. Again, your response seems ideological to me. You are, however, very welcome to visit us, and I invite you to do so because you would see what a traditional education looks like in the inner-city and you would see social mobility working for every single one of our pupils. But if you really dislike us so much, there is always Mercia, in Sheffield, or Tauheedul, in Blackburn. Both schools achieved +2 in their progress, and another 81 schools achieved over +1.5. If you were to visit a few schools like this, you might find that they have something in common: namely a more traditional approach to both teaching and discipline, confidence to use the freedoms they have so they can best educate their kids – the very things you are currently rejecting.

Your response seems ideological to me

There is a lot more I could say about other decisions you have made, but my letter is long as it is. I don’t actually believe you hate poor kids. I just think you don’t know what they need and what true social mobility looks like and requires to succeed.

I would be happy to meet with you and explain, and I repeat my invitation: please come to visit us. You give the impression of having an unreasonable and unwarranted dislike of academies and free schools, blinded by a Marxist ideology. Perhaps if we were to meet, you could point to the ways in which you support academies and their freedoms. After all, it has been these freedoms from the centralised state, demonstrating trust in our country’s teachers and school leaders, that have brought about England’s huge international success, and benefited the poor more than anything else.

Of course, if you are convinced that you do in fact know more than us teachers, then I would happily debate you on a public platform with regard to what works in enabling social mobility for disadvantaged children.

I look forward to hearing from you.

Best wishes,

Katharine Birbalsingh, Headmistress of Michaela

This article is free to read

Subscribe and get your first month of online and app access for free.

Comments

Join the debate, free for a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first month free.

UNLOCK ACCESS Try a month freeAlready a subscriber? Log in