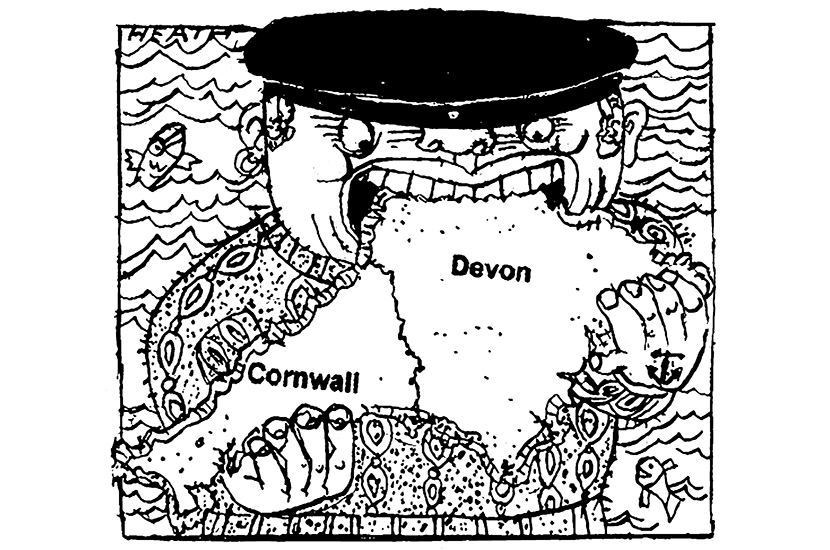

This week, world leaders are doing what countless Brits do every summer: unpacking their bags in a charming corner of Cornwall. The G7 summit — Joe Biden’s first, and Angela Merkel’s last — is taking place in the resort town of Carbis Bay, a stone’s throw from St Ives.

Between the speeches and the roundtables, will the world leaders find time to tuck into Cornwall’s proudest and most popular export, the Cornish pasty? Boris Johnson talked about the region’s industrial history in the run-up to the event: ‘Two hundred years ago Cornwall’s tin and copper mines were at the heart of the UK’s industrial revolution and this summer Cornwall will again be the nucleus of great global change and advancement.’ Well, you don’t invoke tin mining without putting pasties on the menu.

The origin of the pasty is difficult to trace.

Get Britain's best politics newsletters

Register to get The Spectator's insight and opinion straight to your inbox. You can then read two free articles each week.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Comments

Join the debate for just $5 for 3 months

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for $5.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just $5 for 3 monthsAlready a subscriber? Log in