‘I have… found someone to take care of me in the world,’ Marian Evans wrote to her brother in 1857, three years after setting up house with George Henry Lewes. Professing herself ‘well acquainted with his mind and character’, she requested that the modest income from her father’s legacy should in future be paid into her husband’s bank account. A reply from the family solicitor forced her to acknowledge that ‘our marriage is not a legal one, though it is regarded by us both as a sacred bond’. The funds were paid accordingly, but all contact was severed.

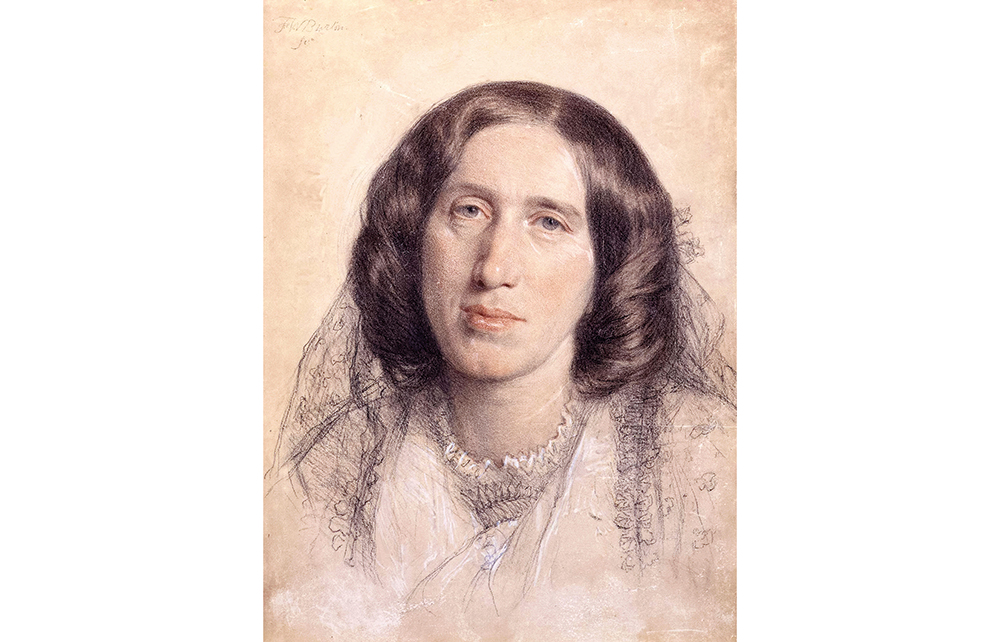

Very soon, money from Evans’s novels – written under the pseudonym of George Eliot – also began pouring into Lewes’s bank account. This was helpful, as he remained responsible for Agnes Jervis, the woman he’d married in 1841 and couldn’t divorce, since he had condoned her adultery. Eliot was actually entitled to hold on to her money, precisely because she wasn’t married. But as the couple’s letters were buried with her, we can only guess why she didn’t. She said: ‘My writings are public property: it is only myself… that I hold private.’ However, the letters to the brother and the solicitor do survive – in Lewes’s hand.

Clare Carlisle teaches philosophy at King’s College, London. Her previous books include studies of Spinoza, and Kierkegaard – who wrote the admirably succinct: ‘Marry, and you will regret it. Do not marry, and you will also regret it.’ Eliot’s philosophy of marriage emerges as more diffuse, if equally inconclusive. Carlisle shows her learning more from Spinoza, whose Ethics she translated during her first months with Lewes. Spinoza argued that if two people sharing ‘the same nature’ lived together, they would become ‘a double individual, more powerful than the single’. Eliot often referred to this doubleness in describing her bond with Lewes – which cost her dearly in terms of other relationships.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in