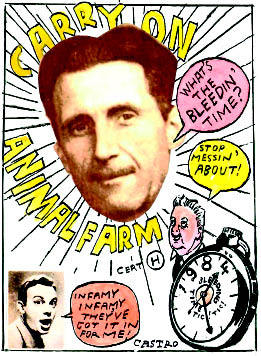

James Walton suggests reading George Orwell in order to understand the appeal of Carry On films

Recently, we’ve been hearing quite a lot about how the winds of revolutionary change blew through Britain in 1968. Which doesn’t really explain why, in 1969, the highest-grossing film at the UK box office wasn’t Midnight Cowboy, The Wild Bunch or Easy Rider — but Carry On Camping. (It didn’t get any better for British cinéastes, incidentally: in 1971, the nation’s favourite movie was On the Buses.) Not that the film in question completely ignored the turbulence of the times. Towards the end, you may remember, the presence of hippies on a neighbouring field caused the solid schoolgirl-chasing yeomen of Britain to come together and drive them out.

Then again, perhaps the bit you remember best from Carry On Camping has nothing to do with 1960s’ cultural wars at all. Instead, it may involve the pinging off of Barbara Windsor’s bra — just one of the many Carry On scenes that’s become part of our collective national memory, along with such moments as the Brits calmly finishing their dinner under fire in Carry On Up the Khyber, Wilfrid Hyde-White with a daffodil up his bottom in Carry On Nurse and (all together now:) ‘Infamy, infamy, they’ve all got it in for me’ in Carry On Cleo.

But, in a way, that’s the trouble with the Carry Ons — which began 50 years ago this August with the release of Carry On Sergeant. Because we know them so well, we can sometimes forget just how peculiar these films are. In my experience, the best solution for this problem is to watch one or two with any educated Americans of your acquaintance. Only then do you have the sudden revelation that maybe not everybody in the English-speaking world understands the innate hilarity of words like ‘it’, ‘one’, ‘pair’ and ‘bullocks’.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in