Whose were those feet in ancient time that walked upon England’s mountains green? That William Blake assumed his readers were on his same wavelength is one of the things, according to John Higgs, ‘that makes his writing a glorious puzzle’. Equally puzzling, argues Higgs, is that the cockney visionary, unsung in his lifetime and buried in a pauper’s grave, has now been absorbed thoroughly into mainstream culture without our having the faintest idea of what he was on about.

Take the 20th-century adoption of ‘Jerusalem’ as England’s alternative national anthem: in its original context as the preface to Blake’s long poem ‘Milton’, the hymn that marks the end of our school terms and party political conferences was intended to describe the overthrow of these very institutions. There is a similar irony, says Higgs, in placing Eduardo Paolozzi’s bronze Newton in the forecourt of the British Library: the object of the Blake print on which the statue is based, ‘Newton: Personification of Man Limited by Reason’, was precisely to challenge the limitations of book-based learning.

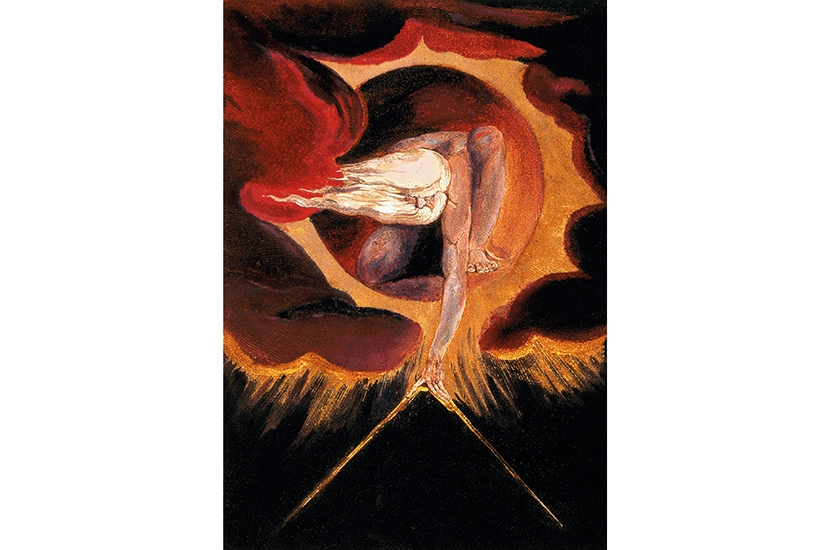

The finest of all our misreadings of Blake, however, was when on 28 November 2019 ‘The Ancient of Days’ was projected onto the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral. Here, squatting naked above the great church with his long hair and white beard blowing in the wind, was Urizen (‘your reason’), marking out with his golden compass the soulless world in which we live. He might look like God but Urizen was, in Blake’s mythology, Satan himself. Higgs explains:

No one has ever understood everything that Blake wrote, possibly including Blake himself. But as Obi-Wan Kenobi asks rhetorically in Star Wars: ‘Who’s the more foolish — the fool, or the fool that follows him?’

In William Blake vs the World, Higgs makes a laudable attempt to explain Blake to the nation and then, to paraphrase Byron, to explain his explanation.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in