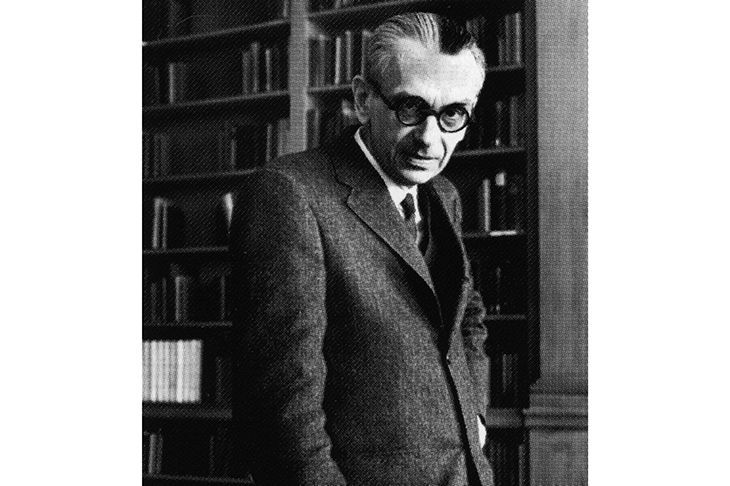

The 20th-century Austrian mathematician Kurt Gödel did his level best to live in the world as his philosophical hero Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz imagined it: a place of pre-established harmony, whose patterns are accessible to reason. It’s an optimistic world, and a theological one: a universe presided over by a God who does not play dice. It’s most decidedly not a 20th-century world, but ‘in any case’, as Gödel himself once commented, ‘there is no reason to trust blindly in the spirit of the time’.

His fellow mathematician Paul Erdös was appalled: ‘You became a mathematician so that people should study you,’ he complained, ‘not that you should study Leibnitz.’ But Gödel always did prefer study to self-expression, and this is chiefly why we know so little about him, and why the spectacular deterioration of his final years — a fantasmagoric tale of imagined conspiracies, strange vapours and shadowy intruders, ending in his self-starvation in 1978 — has come to stand for the whole of his life.

Get Britain's best politics newsletters

Register to get The Spectator's insight and opinion straight to your inbox. You can then read two free articles each week.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in