W.G. Sebald is the modern master of the uncanny — or perhaps that should be ‘was’, as he died in a car crash near Norwich in 2001 at the age of 57. Deciding which tense to use depends on whether you mean ‘W.G. Sebald’ as a shorthand for his body of work, which outlives him, or to refer to the man who wrote it, known to his acquaintances as Max. The question poses its own Sebaldian conundrum, reflecting his strange crepuscular writings with their meditations on the dead and the living, past and present, culture and identity. His ghost lives on in the flickering half-light, the most enigmatic, perhaps, of his characters.

Born in the Bavarian Alps in 1944, Sebald belonged to the generation of Germans whose inordinate moral task was to absorb the Nazi guilt of their parents, a guilt so submerged by shame that it was never mentioned as he was growing up, though it subsequently became the leitmotif of his work. His given name, Winfried, has such a ring of the Third Reich that it is not surprising he abandoned it, as he did his native country. He spent most of his career at the University of East Anglia as a professor of German, but his literary renown is based on the English translations of the extraordinary non-academic writings he began publishing in his forties, especially The Emigrants (1992), which established his international reputation, The Rings of Saturn (1995) and his masterpiece Austerlitz (2001).

In these uncategorisable, liminal books, he slipped the net of genre, blurring the boundaries between fiction, history, essayism and travel writing, to explore issues of memory and buried trauma, most notably that of the Holocaust, through the Jewish refugee characters who people his work. The voice is startlingly original: exquisitely focused yet relentlessly oblique. There’s nothing obviously experimental in his style, which is closer to that of the 19th century than to modernism or postmodernism. And yet paragraphs, and even some sentences, can slide on for pages with an eerie surface calm that disconcerts, as if something is being endlessly avoided.

Most famously, his books incorporate haunting, often slightly blurry, black-and- white photographs from which the real-life dead look out at us, figures from the world of documentary fact who nevertheless give off a paradoxically dreamlike aura, as if they are beseeching us to connect with them but remain just out of reach. A photo of the eponymous Jacques Austerlitz, for example, features on the cover of that book: a serious-faced child in Vandyke fancy dress, a spectral reminder of prewar Prague, where the protagonist’s mother was an opera singer before her son was sent off on the Kindertransport and she herself was deported to a concentration camp.

Jacques is adopted by a sinister Welsh couple, who give him a new name and make him forget who he really is. The novel — though you can’t really call it that, as it features so many non-fiction digressions, including into architectural history — narrates his quest to recover his past and his true identity, but at a tangent. Sebald himself, rather like Lockwood in Wuthering Heights, is the primary yet recessive ‘I’ of the story, to whom Austerlitz recounts his tale.

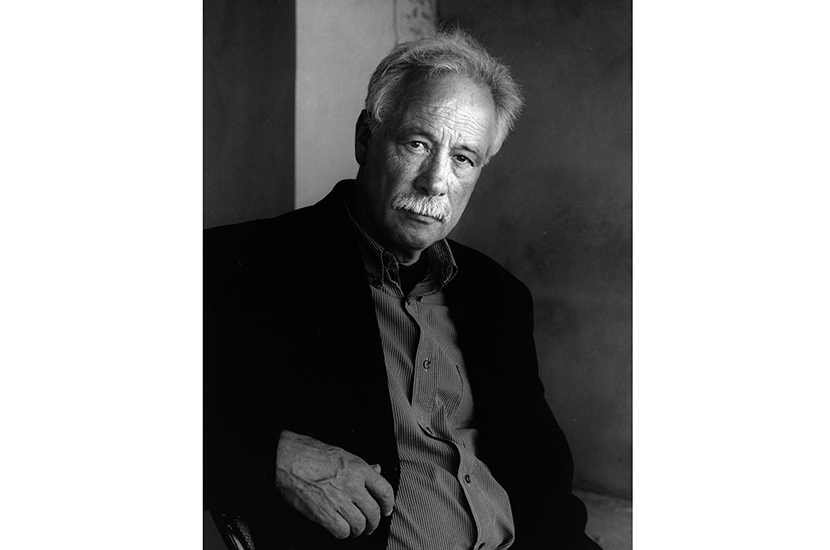

Frank Auerbach, who was reworked as Max Ferber in The Emigrants, found that book ‘repellent’

I have to confess that I’m one of those readers who has always found Sebald’s books obscurely unsettling in their hypnotic magnetism, though I would be the first to pay homage to the astonishing genius of their literary craft. So it came as a jolting anagnorisis to discover from Carole Angier’s biography — the first — that the photo in question is not in fact of a middle-European Jewish child but of a random little English boy called Jackie Grindrod in a prewar country pageant somewhere near Rochdale. It is taken from a vintage picture postcard which Sebald bought in a junk shop for 30p — the price is written on the back.

That would not matter but for the fact that Sebald stated clearly several times in interviews that the photograph was of the real-life model for Austerlitz, someone he knew. First discovered by the critic James Wood, this is not the only example of Sebald’s dishonesty about his historical sources, which is now revealed in more detail by Angier.

We learn, for example, that Dr Henry Selwyn in The Emigrants — a Jewish refugee who remakes himself as an Englishman but ends up committing suicide — is based on a real person, a Dr Buckton, in whose Norfolk house Sebald and his wife once briefly lodged. Angier visits the house (which is accurately described in The Emigrants) and meets Dr Buckton’s daughter Tessa — who reveals that, though her father indeed shot himself, he came from Cheshire, not Lithuania, and ‘didn’t have a Jewish bone in his body’.

Again, that would not matter prima facie. Fiction writers are more than at liberty to draw inspiration from life and transform it anew in whatever way they choose. The problem is the barefaced lies Sebald told interviewers, including Angier herself, who profiled him for the Jewish Quarterly in the 1990s. He explicitly told her that the real-life model for Dr Selwyn was a Jewish émigré from Grodno, confiding that he always had a sense that the doctor whom he met was ‘not a straight English gentleman’, and that this was confirmed when, at a Christmas party chez Buckton, he met an ‘incongruous’ lady, the doctor’s ‘sister from Tel Aviv’.

That was rubbish. There was no such Israeli sister. It was Sebald who was not ‘straight’ — as is evident retrospectively from his digressive, enigmatic literary style. As Dr Buckton’s commonsensical son-in-law puts it to Angier:

The real problem is the photographs. They’re all fakes, aren’t they? They can’t be of the people he says they are. That’s the last thing that anyone should say about the Holocaust, isn’t it — that anything about it could be fake?

Added to that moral conundrum is the intense anger and pain that Sebald provoked in those he never met, whose stories he borrowed for his books. The Holocaust refugee Susi Bechhofer, whose memoir was in fact a key inspiration for Austerlitz, felt cheated. The painter Frank Auerbach, who was reworked as Max Ferber in The Emigrants, found that book ‘repellent’.

Angier — whose self-imposed brief is to disentangle the life from the work, the fact from the fiction, W.G. Sebald from Max — is well aware that she has chosen the most elusive of subjects. Her title, Speak, Silence, is aptly chosen (with its nod to Nabokov’s Speak, Memory). Sebald grew up in a world of the unspoken, with an obscure feeling, as he put it, that there was ‘some sort of emptiness somewhere’, some ‘silent catastrophe’. His authoritarian father, an army corporal with whom he was always in conflict, answered all questions about the war with ‘I don’t remember’. His Uncle Hans, who lived near Dachau, denied all knowledge of the camp there, asserted that the Germans were not responsible for what happened to the Jews, yet kept a copy of Mein Kampf in his spare bedroom.

Only in his teens did Sebald first begin to apprehend the conspiracy of silence, when his school was shown a film on Bergen-Belsen, which was received in silence, without comment. When, around the same age, he took a Swiss friend to stay with Uncle Hans he affected not to notice the book on the bedside table and said nothing.

As a biographer, Angier has had to contend with so many silences that she describes her biographer’s work, the product of years of sleuthing, as ‘a matter of joining holes together like a net’. The most resounding personal silence is that of Sebald’s wife, Ute, to whom he was married for 30 years but who ‘did not want to speak’ or indeed be included in the biography at all, with the result that she does not even merit an entry in the index. Sebald’s day-to-day intimate life thus remains a blank. The one fact about Ute we discover is that she was, perhaps surprisingly, working in a beauty salon at the time the hyper-intellectual Sebald met her. We hear nothing about their daughter Anna, who was in the car with Sebald when he died but survived the accident.

In life, Sebald rarely spoke openly about himself — an inhibited, morose presence to most who met him. As one of his colleagues at UEA recalled, he always seemed ‘not quite in himself’. Angier’s openness about the difficulties she has encountered in trying to untangle his enigma if anything adds to her portrait. Moreover, despite the gaps, she has doggedly succeeded in interviewing a host of people who knew him, including his sister, friends from his early years, co-workers, pupils and the mysterious ‘Marie’ (no surname given) who first knew him in childhood and then became briefly close to him in later life. The details Angier heroically marshals at times verge on the distracting, but the portrait which ultimately emerges convinces: of a tormented man, an isolated misfit, riven by self-doubt, who wrote to stave off depressive breakdowns and even madness and suicidal impulses.

Another weird lacuna is that, though she chronicles them, Angier cannot make sense of the strange, unnecessary, repeated lies to interviewers which Sebald must have known would have put him at risk of exposure as a fraud. Why did he tell them? He could have said nothing at all, or explained that he had to use, say, an evocative junk- shop photo as a surrogate for ‘Austerlitz’to demonstrate how many people were actually lost to history, their faces unrecorded.

A further bizarre detail is that in 1991 he penned an excoriating attack on a Jewish writer, Jurek Becker, a Holocaust survivor, dismissing his books as a failure — inauthentic, fake — because, in Sebald’s view, the author could not allow himself real memory. This seems more than odd, given the imagined memories Sebald later invented for his Jewish characters. Luckily for Sebald, that essay was rejected.

For a German writer to accuse a Holocaust survivor of inauthenticity looks like a bid for reputational suicide. My hunch is that such weird, potentially self-cancelling behaviours, including the untruths he told about the factual background of his works, are linked at some deep level with Sebald’s legacy of self-hatred, lies and silence, his role as a vector for German guilt. Does recognising this problematic moral hinterland mean we have to reject his work and its seeming empathy with Jewish characters? Certainly not. Its extraordinary literary qualities are ambiguously enhanced by our knowledge of his tortured relationship both with truth and with himself.

Comments