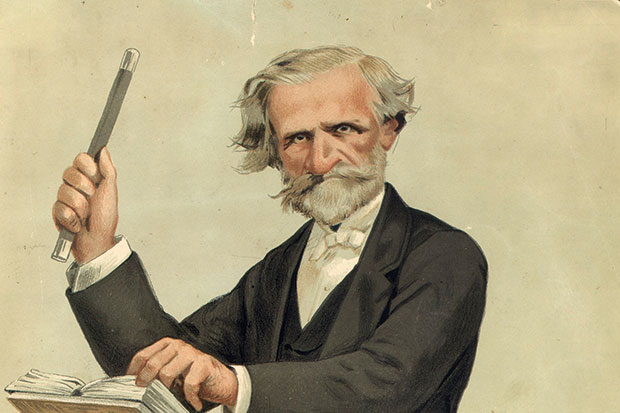

Verdi has a peculiar if not unique place in the pantheon of great composers. If you love classical music at all, and certainly if you love opera, then it is almost mandatory to love him. The great and good of the musical world, the kind of people who sit on the boards of opera houses and other cultural institutions, go out of their way to advertise their adoration of Verdi, usually at the expense of the other considerable operatic composer who was born a few months before him in 1813, Wagner. In fact, Verdi’s status and stature are often established by comparing the two. Verdi was a decent man from a lowly background who, through hard work, built an oeuvre which, lacking pretensions to any kind of revolutionary methods or goals, nonetheless reveals human nature in its essence (at least according to Isaiah Berlin in a famous essay). Comparisons with Shakespeare are not uncommon — and given that Verdi set versions of several Shakespeare plays to music, they are inevitable.

And yet you have only to compare Macbeth and Macbeth to see that the play is in a different artistic class to the opera, exciting and sometimes moving as that is. Much the same can be said of Othello and Otello. Falstaff, utterly unlike any of Verdi’s other operas, is a far greater piece than The Merry Wives of Windsor, but that play is feeble and Nicolai had already composed a far superior version of it. Verdi’s art is almost always simple, which is perhaps one of its major charms. You can have a thoroughly enjoyable evening out watching Rigoletto, and feel no need to reflect on it afterwards or allow it to affect your post-opera supper.

Magazine articles are subscriber-only. Get your first 3 months for just $5.

SUBSCRIBE TODAY- Free delivery of the magazine

- Unlimited website and app access

- Subscriber-only newsletters

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in