It’s German Season in London, and revealingly the best of three new shows is the one dealing with the most modern period: the post-second world war era of East and West Germany and the potent art that came out of that split nation. In Room 90 is another immaculately presented British Museum show of prints and drawings, focused this time around Georg Baselitz (born 1938). Of the 90 works on display, more than a third has been donated to the BM by Count Christian Duerckheim, the remainder lent by this assiduous collector.

The show begins with Baselitz’s contemporaries and I was surprised to find myself quite liking some things by Gerhard Richter, currently the most overrated artist in the world. Not his traced-from-photos Pop Art drawings but four watercolours, his first in the medium, together with his smudgy graphite drawings of a hotel and pedal-boat riders. A flat cabinet of Sigmar Polke’s drawings comes as light relief and a series of blue watercolours by A.R. Penck is more expressionist and direct than his usual cybernetic stick-figure language. Marcus Lüpertz comes across strongest here, with savage drawings of helmet heads and a richly structured gouache entitled ‘Monument — dithyrambic’ (1976), slightly reminiscent of John Walker. This is art with real bite.

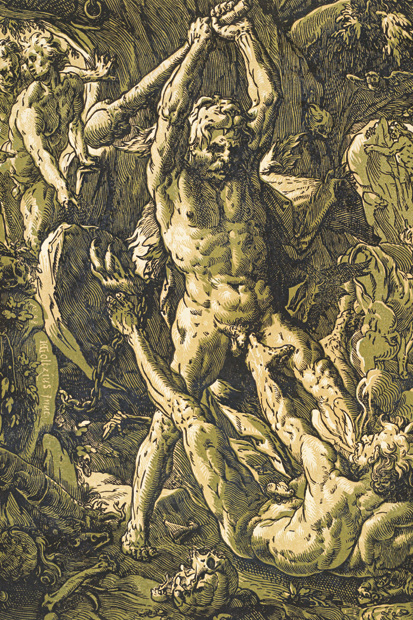

On this showing, the only good thing about Blinky Palermo is his name, but the star of the show is Baselitz, who is given the whole of the second half of this large gallery. Whatever you think of his characteristic upside-down imagery (which he initiated in 1969, conceiving, composing and executing his work thus thereafter), his best work is deeply affecting and often uncomfortable. Baselitz was inspired by Renaissance chiaroscuro woodcuts, which he began to collect and emulate, and various of these — by Urs Graf, Ugo da Carpi and Hendrik Goltzius — are exhibited beside his own efforts.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in