What should a writer write about? The question, so conducive to writer’s block, is made more acute when the writer is evidently well-balanced, free of trauma and historically secure. It is made still more urgent when that writer is solipsistic in tendency and keen to write, not about the world, but about perceptions of the world.

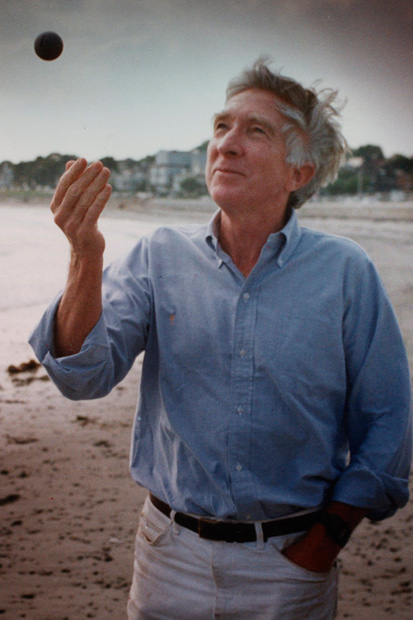

Two American authors of the same period arrived at different solutions to the problem. Sylvia Plath, in her husband Ted Hughes’s assessment, first found nothing worth writing about, and then deliberately encouraged demons and hitherto controlled minor difficulties until they flared up and killed her. John Updike, on the other hand, had an immensely long and sustained writing career, with few troubles to cope with other than psoriasis. His childhood was very happy, apart from a slightly disruptive move. As an adult, he met with immediate acclaim and success, which never entirely left him. What on earth was there to write about, to satisfy the immoderate itch that equally afflicts the talented and the untalented, the event-torn and the calm life?

Adam Begley’s interesting biography is largely an act of piety, but it may in the end contribute to the case for the prosecution. It begins with a truly startling example of Updike’s habitual creative process. A journalist came to interview him in 1983, and published the resulting article in the Philadelphia Inquirer on 12 June. Less than a month later, Updike published a short story in the New Yorker, efficiently translating the routine experience of being subjected to a provincial newspaper’s inquiries into well-turned fiction.

It was not a one-off. In 1972, for instance, a three-week vacation around the western states of America, in June, led to Updike ‘recycling his impressions in a short story — an expert distillation of the trip — and selling it to the New Yorker, which ran it in mid-August’.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in