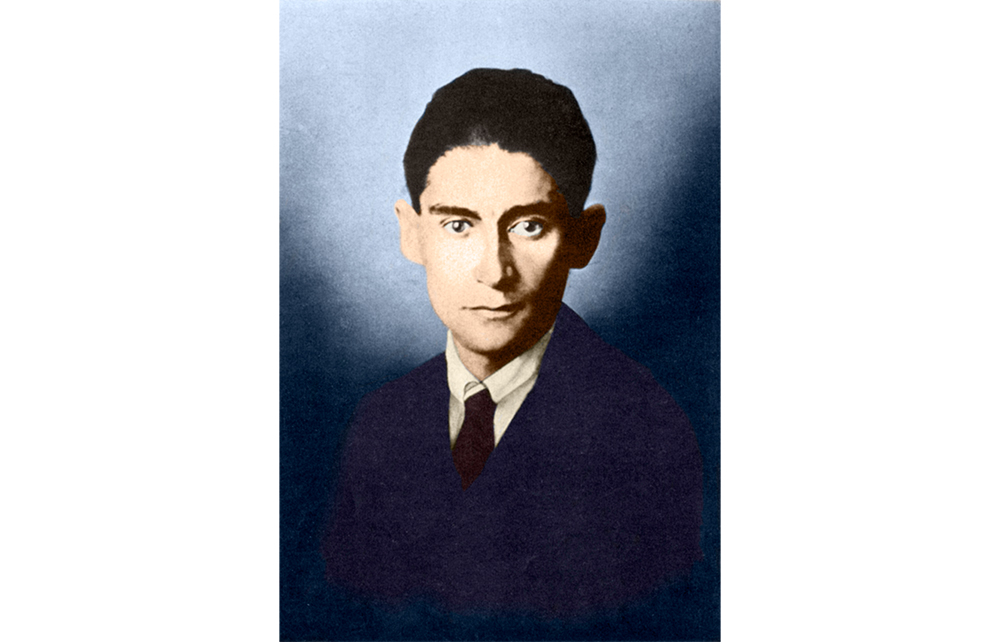

Two books in one: you flip it over, and it becomes the other. A Winter in Zürau is about Franz Kafka’s stay in a small Bohemian village with his sister Ottla after being diagnosed with tuberculosis. Or, as Gabriel Josipovici arrestingly puts it in the preface: ‘One day in the summer of 1917 the writer Franz Kafka woke up to find his mouth full of blood.’ (The echo of the opening line of Metamorphosis is surely deliberate.) Here, in isolation, he recuperated, or tried to. He wrote to Max Brod: ‘I’m not writing. What’s more, my will is not directed towards writing. If I could save myself… by digging holes, I would dig holes.’

Josipovici quotes this, and adds that there is a photograph of Samuel Beckett ‘doing just that’ in the second volume of his Collected Letters. Josipovici likes mentioning Beckett from time to time, which pleases me. But Kafka, as so often in his letters, wasn’t telling us the whole story. Of course he wrote in Zürau – he was Kafka, for goodness’ sake – and he produced what Brod eventually collected under the title of The Zürau Aphorisms, or, less snappily, Reflections on Sin, Hope, Suffering, and the True Way.

The 181 pages of Josipovici’s monograph, if that is the word, are difficult to summarise, but they are a mixture of biography, literary criticism and psychological insight, and make up one of the best things on Kafka I have read. As his previous volumes of literary criticism and essays attest, Josipovici is astonishingly readable; his prose simply takes you by the hand. At one point he quotes Kafka complaining about mice, but also about the cat that was meant to deal with them, which keeps soiling his room. (‘How hard it is to arrive at an understanding with an animal on this question.’)

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in