Oddly enough, one of the most historically influential pieces of British writing has turned out to be an essay that appeared in the June 1800 issue of the Commercial, Agricultural and Manufacturers Magazine. Over the preceding decades, there’d been much anguished debate about the size of the country’s population. Many commentators were convinced that, thanks to the gin craze, it was in potentially disastrous decline. Others, led by Thomas Malthus, were convinced that it was on the potentially disastrous rise. The biggest question of all, though, was what the population actually was, with most estimates — or, as it transpired, wild guesses — ranging from four million to six million. But then, in that 1800 essay, amid his magazine’s more usual fare of articles on manure and cowpox, the editor John Rickman came up with a radical suggestion: why not count it?

Fortunately, he was sufficiently well-connected for his argument to be taken up by a couple of friendly MPs — and, with the government desperate to know how many soldiers it might be able to muster against Napoleon, Britain’s first census was soon commissioned, under Rickman’s direction.

In fact, suspicion of what the government was up to made the 1801 census a fairly hit-and-miss affair. Nonetheless, its figure of around 15 million for the inhabitants of Britain and Ireland wasn’t too far wide of the mark. It was also considered successful enough for a census to be recommissioned every ten years from then on, with ever more accuracy, and ever more information about the inhabitants’ lives. By 1831, Rickman was convinced that he’d seen off both sets of doom-mongers by proving that the country’s population and prosperity were growing together nicely.

Using the census records as the basis for a history of Britain is clearly an excellent idea for a book. Even so, Roger Hutchinson has carried it out particularly well. The ten-yearly snapshots allow him to identify the precise timing not only of the most profound social changes (between 1821 and 1831, the expansion of Britain’s cities was ‘breathtaking’), but also of the more minor ones (between 1851 and 1861, the number of professional photographers increased nearly 60-fold).

Happily, too, he manages to do this without the result ever becoming merely a blizzard of statistics. Admittedly, if you have ever wondered how many Brits made artificial flowers for a living in 1851, then here’s where you’ll find out. (Spoiler alert: it was 3,510.) Yet Hutchinson’s sharp eye for the telling detail, his deft use of individual stories to illustrate the wider trends and his willingness to throw in any vaguely related facts that he (rightly) thinks we might find interesting make this a book to read with much pleasure, rather than simply to consult.

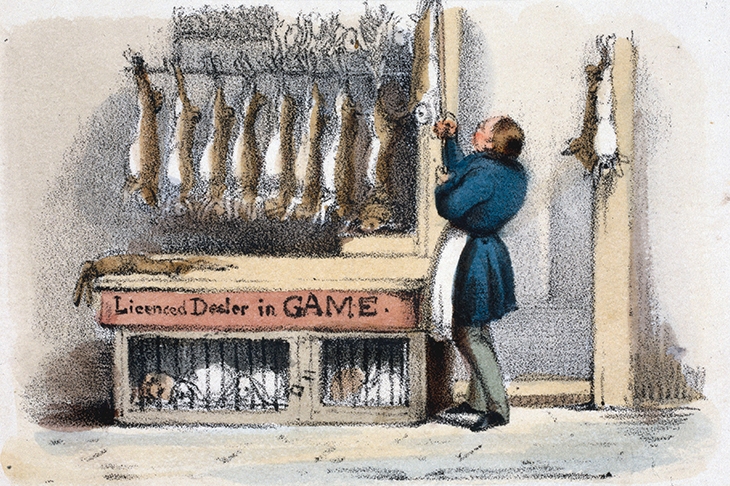

Take, for instance, one of his biggest themes: the changing nature of work. The growth, and later the decline, of heavy industry are duly laid out in forensic detail. But along the way we also learn that, by 1881, there were so many new types of job that the census-takers had to commission a special dictionary to help them understand such occupations as ‘crutter’, ‘spragger’, ‘whitster’ and ‘oliver man’. More deliberately misleading, meanwhile, was ‘seamstress’: apparently the self-description of choice for most prostitutes.

You might also be surprised by how many billiard-markers and slaves there were in 1911 — until Hutchinson points out that, back when many sports forbade players from being paid, their clubs would pretend to employ them in billiard halls; and that married women calling themselves slaves was part of a protest campaign organised by the suffragettes.

On the whole, Hutchinson shares the essentially sunny approach of John Rickman, the book’s chief hero. But some censuses, naturally, make cheerfulness impossible. In 1921, the decline in the number of young men since 1911 was as unmistakable as the rise in the number of widows. As for Ireland — the source of much of the book’s gloom — the post-famine census of 1851 (partly conducted, as Hutchinson characteristically adds, by Oscar Wilde’s father) discovered a population loss of more than 1.6 million in a single decade.

But if some of the events it illuminates feel almost unimaginable now, the book contains plenty of plus ça change moments too. As long ago as 1851, it seems, people had a tendency to exaggerate the importance of their jobs. (‘Many of the 2,971 architects are undoubtedly builders,’ reported the census-takers rather sniffily.) There’s also the 1931 census — which contained what many felt to be worrying evidence of Britain’s growing London-centricity. ‘It looks as if London were becoming almost dangerously the Capital of the country,’ reflected the historian Godfrey Elton — although he did find one organisation obstinately trying to buck the trend. ‘Decentralisation is being undertaken to a very considerable extent,’ henoted, ‘by the British Broadcasting Corporation.’

Comments