Sam Leith has narrated this article for you to listen to.

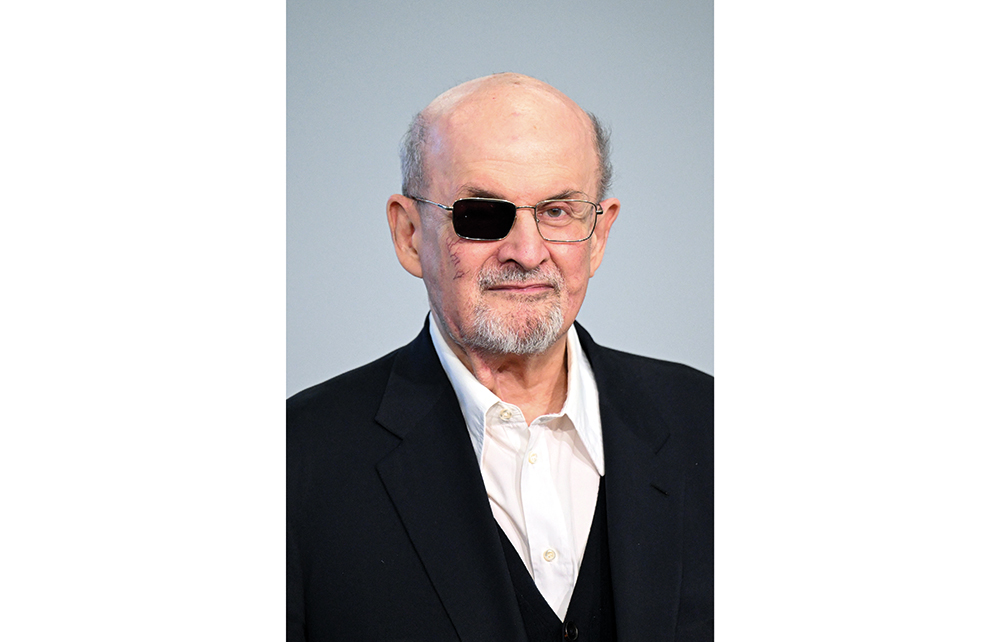

Salman Rushdie has long hated and struggled against the idea that the 1989 fatwa pronounced on him after the publication of The Satanic Verses should define his career or his life. It was, as he frequently pointed out, a book he published only a quarter of the way through his career.

Disagree with half of it, enjoy reading all of it

TRY 3 MONTHS FOR $5

Our magazine articles are for subscribers only. Start your 3-month trial today for just $5 and subscribe to more than one view

Already a subscriber? Log in

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in