Rhinoceros by Eugene Ionesco is a period piece from 1959. It opens with the invasion of a French village by a herd of rhinoceroses. This paranormal event is never explained. In Act Two, the villagers start to imagine that they’ve become rhinoceroses and changed species. But one plucky sceptic, who defies conformity, refuses to swap his human character for an animal alternative. That’s it. Ionesco is offering the same arguments about peer-group pressure that Arthur Miller made with far more grace, artistry and psychological penetration in The Crucible.

The show can’t decide what register to aim for and the cast are dressed in a mishmash of cheap costumes. Some wear white coats like asylum orderlies and some are in Primark expendables. Many of them scream or honk out their lines in grating voices. Ionesco’s script adds to the noise and confusion.

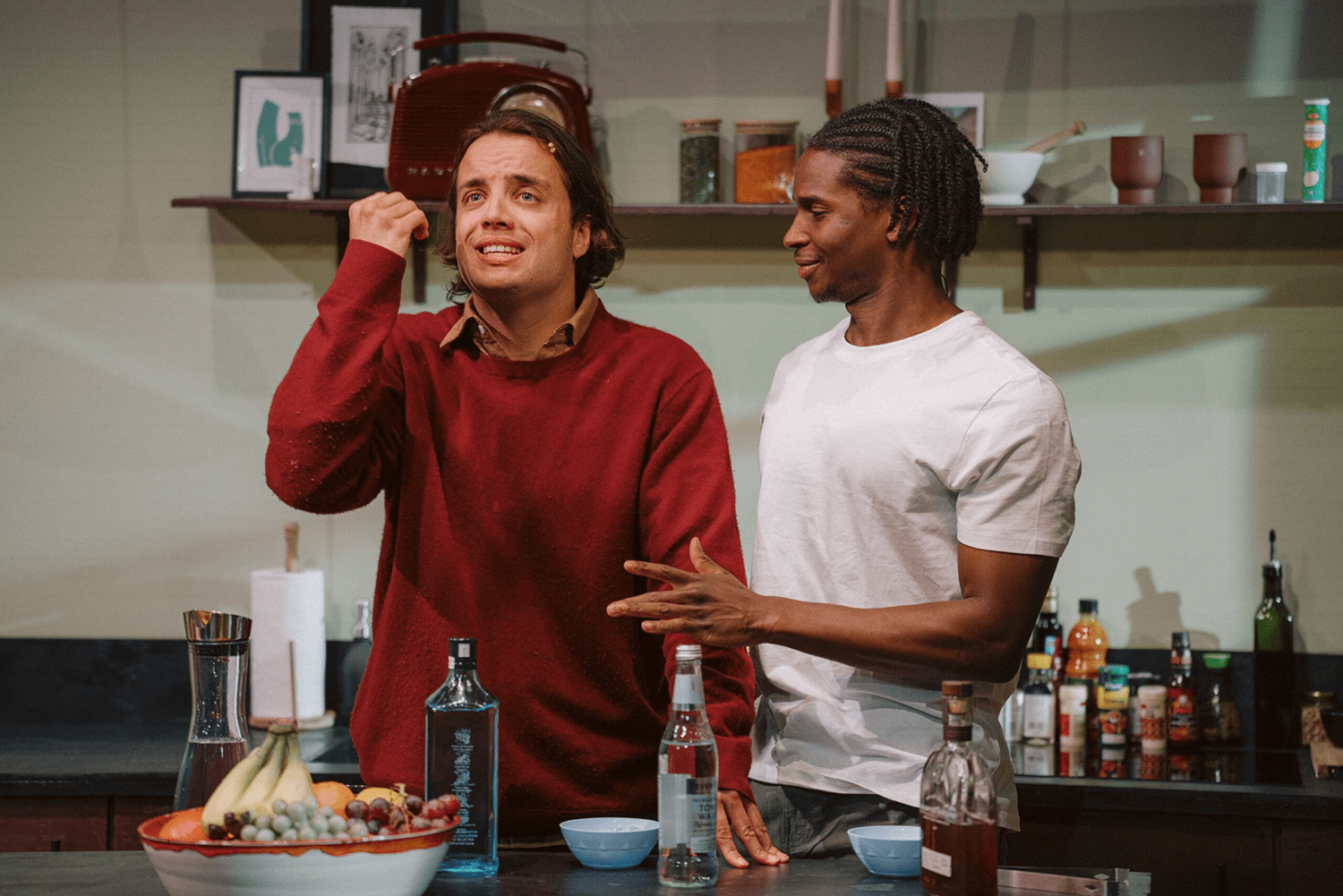

The show begins with a compère who warms up the crowd by doing arm-stretching exercises, as if the Almeida were a care-home for dribbling old crocks. Then the play begins and the main characters, Bérenger and Jean, meet in the village café. Ionesco has no interest in human beings and his characters are as absorbing as teddy bears or plastic flowers. And the surreal storyline moves at the pace of smog.

These faults are concealed by arrival of several prattling commentators, who discuss Jean and Bérenger using a pastiche of the pretentious chitchat favoured by academics. The play keeps switching focus from the events on stage to a literary analysis of those events, and back again. Audacious in 1959, perhaps. Not any more.

A third layer of narrative complication is added.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in