A tale of two opera companies from the Land of Song. After its distinctly gamey new Cosi fan tutte, Welsh National Opera has sprung dazzlingly back to form with a new production of Benajmin Britten’s final opera, Death in Venice. It’s directed by Olivia Fuchs, in collaboration with the circus artists of NoFit State, and in a word, it’s masterful.

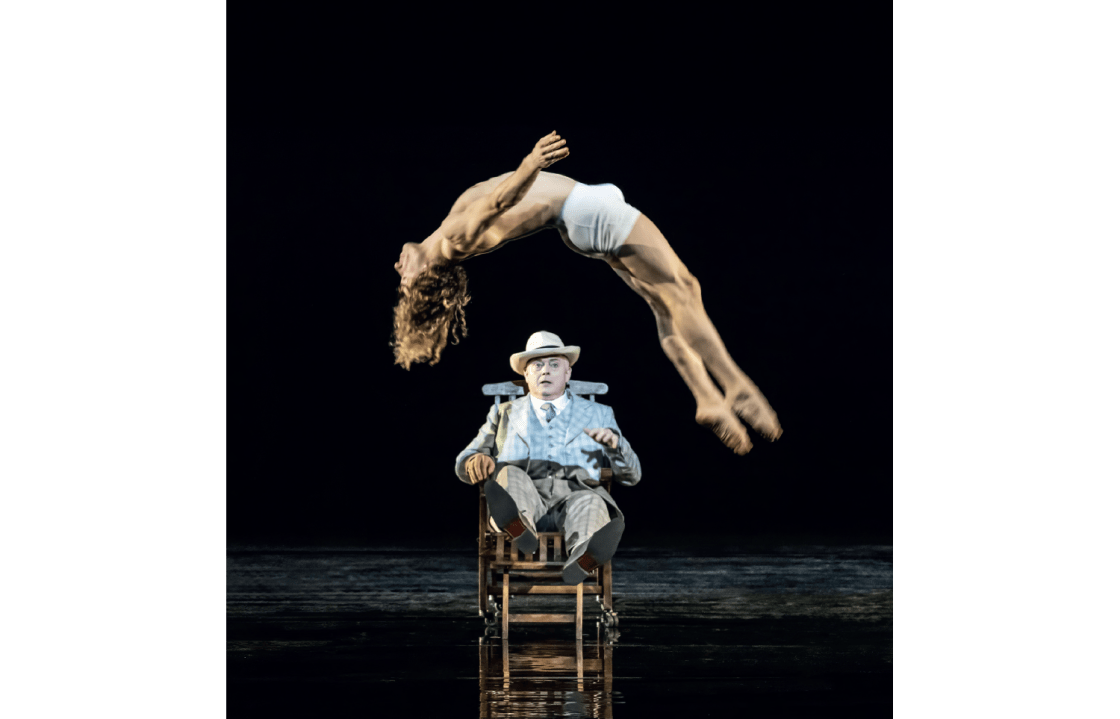

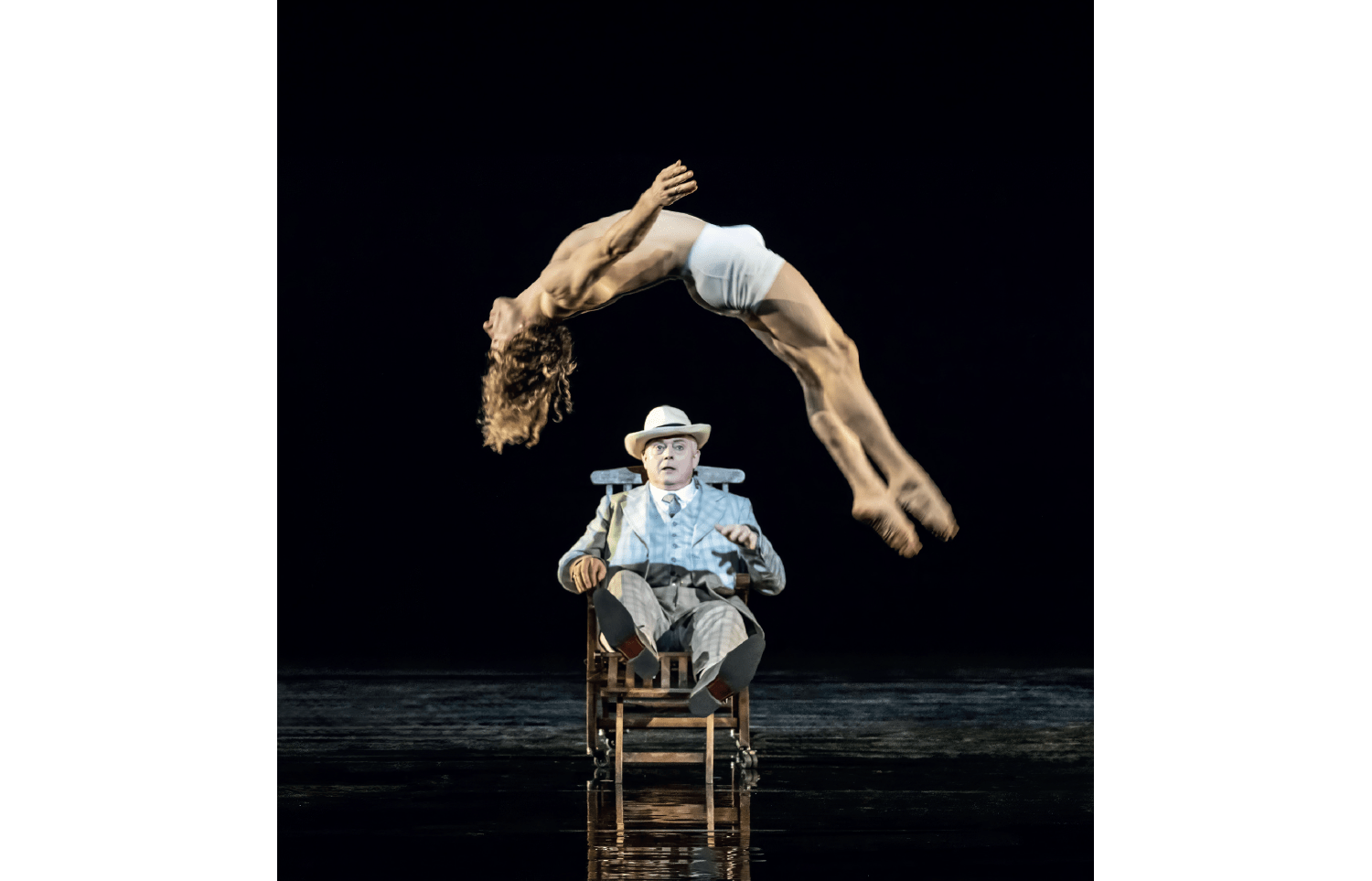

Fuchs’s Serenissima is a city of shadow, its landmarks glimpsed distantly in smudged, restless scraps of black and white film. The tourists and locals wear monochrome period dress; only Aschenbach (Mark Le Brocq) is in a noncommittal grey. The colour has drained from his world and from the peripheries of the stage he gazes, impotent, at the figures who dance and sport in the light, played by the acrobats and aerialists of NoFit State. It’s not just the muscular teenager Tadzio (the panther-like Antony Cesar) who lives on an elevated plane: the whole Polish family are figures of fantasy – frequently airborne and unashamedly, gracefully physical. There’s a lot of semi-nudity, and it’s not only the male form that gets fetishised.

Those who think lovely, flute-playing Sir Keir will rescue opera should look at Labour-run Wales

It’s been suggested that Britten’s extended beach ballet sequence saps the momentum of the drama, and that seems unarguable. If performers this good and an imaginative vision this strong can’t prevent it from dragging, then nothing can. But that’s Britten’s fault, and he’s not around to authorise rewrites. In every other regard, this Death in Venice is strange, beautiful and troubling, with WNO chorus members providing crisply etched cameo roles. The orchestra, under Leo Hussain, shimmers with the iridescence of decay, playing with needlepoint finesse as Britten dissects Aschenbach’s disintegrating personality.

Le Brocq is absolutely exceptional, by the way: one of those anti-virtuosic virtuoso performances where the artist vanishes so completely inside the character that it almost feels tactless to mention the technical niceties – his bleached, aching tone; the way it loosens and ripens as Aschenbach loses his grip, and the exemplary clarity and sensitivity with which Le Brocq articulates the text.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in