Nicholas Lezard has narrated this article for you to listen to.

How do you see Franz Kafka? That is, how do you picture him in your mind’s eye? If you are Nicolas Mahler, the writer and illustrator of a short but engaging graphic biography of the man, you’d see him as a sort of blob of hair and eyebrows on a stick. The illustrations of Completely Kafka may look rudimentary, but they work. In fact they’re similar in style to the doodles Kafka himself would make in his notebooks.

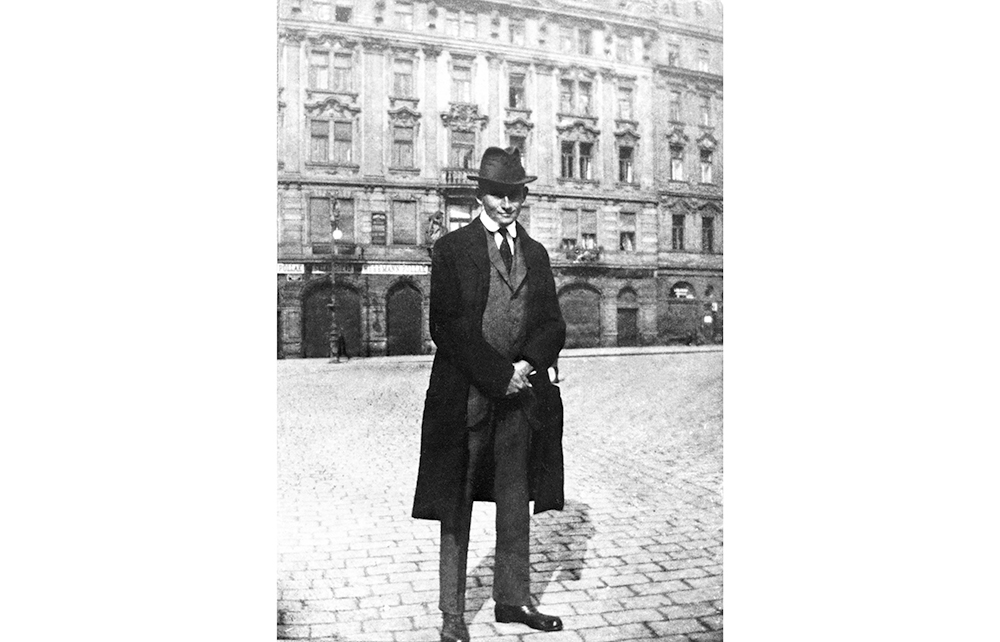

If you were Kafka, you’d see yourself as a spindly man, head on desk, leaning on your hands, arms bent, in a posture of defeat and exhaustion. That image is chosen for the cover of a translation by Mark Harman of Selected Stories. But if you are Penguin, publishing a new edition of the Diaries, you’d use the photograph (reproduced) of Kafka in his late thirties, standing in a Prague square, eyes hidden by his hat’s brim but with an amused smile on his lips.

Photographs of Kafka are always of a young man, since he died of tuberculosis at the age of 41. (His death was in 1924 – hence the present glut of books by and about him.) The Prague photograph is well chosen, because it reminds us that there is humour in Kafka, and that he wasn’t solely the prophet of a century of dehumanisation. And at least none of the books I’ve seen have a drawing of a giant beetle on the cover.

Kafka’s early work wasn’t quite as sui generis as you might imagine. When first published, he reminded people of the Swiss author Robert Walser, whose naive style was unlike what we think of Kafka today – as the chronicler of uneasy dreams. Harman translates unruhigen, in the opening sentence of Die Verwandlung, as ‘restless’. In meticulous footnotes he tells us why he has chosen to translate certain German words the way he has. For example:

‘Nailed fast’ (fastgenagelt). Like its English counterpart, the German expression is so common that it has lost much of the literal meaning that it once had. Nevertheless, this mention of Gregor [Samsa]’s being ‘nailed’ has supplied grist for interpretations of The Transformation as a kind of radically revamped Passion story, with Gregor as the suffering Christ.

We are reminded that there is humour in Kafka, and that he wasn’t solely the prophet of dehumanisation

There are many footnotes like that – informative and judicious, not imposing any rigid interpretation but suggesting them. The endnotes are also useful, as when Harman observes that three mentions of fur should remind us of Leopold von Sacher-Masoch’s Venus in Furs. ‘Gregor’ is the pseudonym the protagonist Severin adopts when in the service of the dominatrix of the title. The apparatus to the Selected Stories takes up almost half the book, but it is not a burden at all. It is very welcome.

There are plenty of endnotes to the Diaries too: 1,403 of them, to be precise. This may look overwhelming, but it works out at not much more than two a page, which is hardly excessive. On the other hand, 670 pages might seem that; yet Kafka – for all that people say ‘but he’s also funny’– is a serious writer, and needs to be taken seriously.

The notebooks that contain the material that forms the Diaries aren’t exactly bristling with gags, but they are certainly worth reading. ‘Diaries’ isn’t quite the right word, since by no means are all the pieces dated. One entry might be followed by another from a year later, in the haphazard way in which we keep notebooks – not intended for posterity but simply as aides-mémoires, to be discarded or expanded elsewhere.

Max Brod, who ignored Kafka’s instructions to burn his unpublished writings, smoothed the notebooks into something more homogenous and less chaotic. As well as long sections of works abandoned or later hugely modified, we get random, enigmatic utterances. Many of these the editor and translator Ross Benjamin explains or attempts to contextualise in the notes, but there are also many that he doesn’t. For instance: ‘I tighten the reins’ – a sentence which stands alone between the entries for the 1 and 2 August 1917. I am not enough of a Kafkologist to try to link this to anything else in his oeuvre; but Benjamin doesn’t try either. These unsupported utterances reinforce the impression of our being close to the reality of what these Diaries actually are.

Brod also removed the occasional unflattering reference to himself and played down Kafka’s sexuality, which seems, in modern parlance, to have swung both ways. Some think Brod had too heavy a hand when it came to editing the notebooks. But he saved them from the flames, so as far as I’m concerned he could do with them what he liked, as long as the originals survived. In his preface, Benjamin tells us what he, and Brod, were dealing with:

Twelve quarto notebooks and two bundles of loose paper filled with dense handwriting, crossings out, corrections and insertions squeezed in wherever possible, between the lines, in the margins, drawings here and there.

So not impossible, but not a walk in a Prague park, either. He continues:

Their afterlife has consisted of a long, complex and fraught reckoning with the question of what fidelity to the original means in this special case.

This edition of the Diaries seems a model of both scrupulousness and generosity. Here we find the unpolished inner life of one of the most significant writers that ever lived; and the entries, which come from the mind of an ordinary human being and not from some otherwordly realm of inner consciousness, do not in any way detract from Kafka’s work. They often show, as the photograph of Kafka in Prague suggests, a man wryly amused by his surroundings, and the ways of the world. The Great War troubles him hardly at all, exempted as he is by poor health. Marching tunes get stuck in his head: that’s about the size of it.

If there is one entry, though, that encapsulates his work, his method, his way of thinking, it is a single, unsupported sentence, undated, but presumably written in September 1912: ‘I, only I, am the observer of the ground floor.’ What does he mean by this? The base, ground floor of the human soul? The apartment block, behind him in the photograph, where his parents lived? Benjamin doesn’t say, and I’m glad he doesn’t. It’s a sentence that’s been haunting me for weeks.

Comments