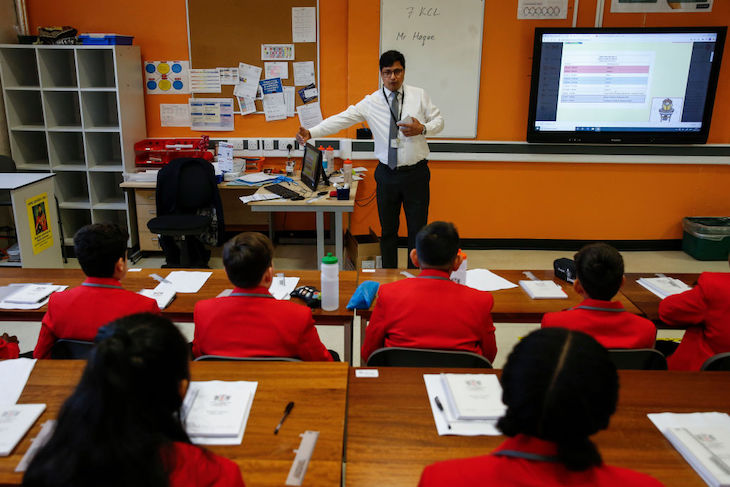

Teacher recruitment levels are in crisis, and have been for some time. Only half the number of secondary teachers needed for this academic year have actually been recruited, according to figures obtained by the National Education Union (NEU) and the National Association of Head Teachers (NAHT). Teacher vacancies have doubled since the start of the pandemic, while one in five teachers who qualified in 2020 have already quit; even the previously reliable juggernaut Teach First has been branded ‘inadequate’ over its ability to recruit by the Department for Education. What’s more, the shortage of male teachers has led to a worrying gender imbalance.

Yet despite these worrying figures, politicians – and the public – seem to be suffering from ‘crisis fatigue’, a sense of exhaustion and burnout from prolonged adversity: yes, I know things are really bad, but what can we really do? After a decade of austerity and a global pandemic, and now faced with a housing crisis, a cost of living crisis, an energy crisis, an NHS waiting lists crisis, and all the rest, it’s easy to feel apathetic.

Get Britain's best politics newsletters

Register to get The Spectator's insight and opinion straight to your inbox. You can then read two free articles each week.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in