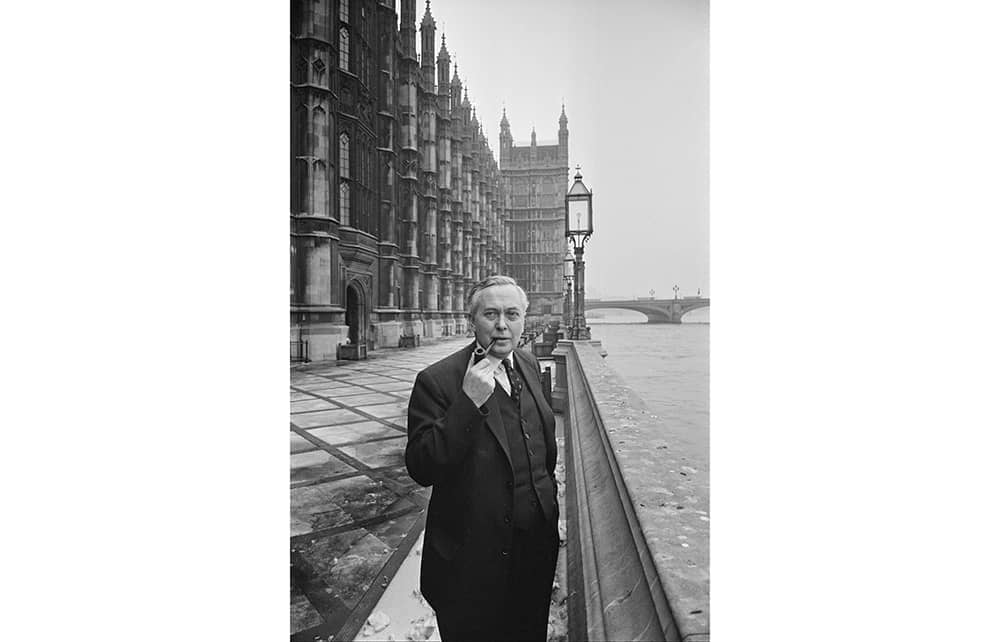

‘Our generation owes an apology to the shades of Harold Wilson,’ the polling guru Peter Kellner once told me. Had Wilson not firmly resisted pressure from President Lyndon Johnson to send troops to Vietnam, Kellner and I were both old enough to have fought there. But in 1968 we loftily despised Wilson for twisting and turning to stay out of Vietnam and keep his party together.

Disagree with half of it, enjoy reading all of it

TRY 3 MONTHS FOR $5

Our magazine articles are for subscribers only. Start your 3-month trial today for just $5 and subscribe to more than one view

Already a subscriber? Log in

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in