The 17th-century diplomat Sir Henry Wotton said that an ambassador was ‘an honest man sent to lie abroad for his country’. It is a neatly punning definition. An ambassador is a messenger, who has to live (lie) abroad long enough to understand the interests, the preoccupations and the driving emotions of the people he deals with. He has to be honest if his own government and his foreign interlocutors are to trust him to manage their business effectively. He may occasionally have to be economical with the truth to further his government’s interests. If he doesn’t relish that, he can resign; few do. He may find himself disobeying his masters’ instructions if that is the only way he can achieve what they need. The work is rarely glamorous (the champagne and chandeliers are usually conspicuous by their absence), often tedious, sometimes dangerous. Nevertheless, if you’re lucky, it can be very satisfying.

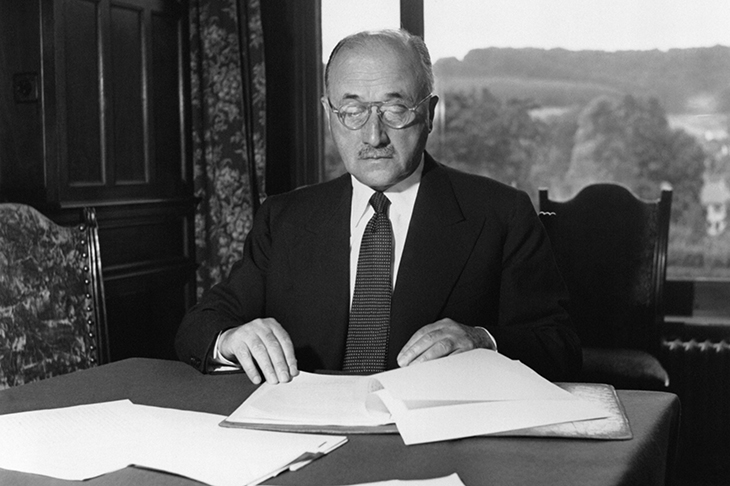

Robert Cooper has a lifelong experience of diplomacy in the British Foreign Office and the European Union. His new book is based on wide reading and meticulous attention to detail. It is fluently written in a limpid and comfortable prose. Despite its title, it is not really about ambassadors at all, though it shows in passing how Anatoly Dobrynin, the wily and well-connected Soviet representative in Washington, played just the role an ambassador should in the midst of the Cuban missile crisis.

The nub of what Cooper has to say is a subtle analysis of the nature of international relations and the creative way brilliant people have used a combination of diplomacy and force to manage the convoluted problems which relations between countries always throw up. After a skirmish with Machiavelli and Richelieu, whose ideas and actions he skims over in an elegant telegraphese which will leave some readers baffled, he embarks on a vivid and penetrating account of the major international crises of the past 70 years and the people who handled them.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in