In September 1944, a few months after being greeted by cheering crowds in Paris, Marshal Philippe Pétain, the head of the wartime État Français, was driven across the German frontier into exile under Gestapo escort. He no longer had access to the national radio service, so, as he passed through France, typed copies of his last speech had to be thrown to passers-by from the window of his car. Julian Jackson, the author of a previous magisterial biography of Charles de Gaulle, now undertakes a more complex task in telling the story of Pétain’s subsequent three-week trial for treason in 1945. The novelist and resister François Mauriac summarised the ordeal as the ‘trial that is never over and will never end’. Jackson describes it as ‘the central crisis of 20th-century French history’.

Pétain sat in passive silence, leading many to wonder how much of the evidence he could understand

He opens this absorbing account with a vivid description of Sigmaringen, the castle in southern Germany where the Gestapo escort eventually lodged Pétain, and where he stayed with his demoralised government for seven months until the Nazi leadership surrendered. At Sigmaringen, the fallen head of state presided over a Ruritanian chamber of horrors. As chief waxwork, he was rewarded with a floor of the schloss to himself. His pro-German prime minister Pierre Laval was restricted to a lower floor, with an inferior menu consisting largely of potatoes and cabbage. If Laval’s ulcer played up, he could call on the deranged anti-Semite novelist and medical doctor Louis-Ferdinand Céline for expert attention. From the windows of the castle, Pétain could glimpse the solitary figure of Joseph Darnand, his minister of the interior and commander of the murderous French Milice (militia), strutting around the park in his Waffen-SS uniform.

Pétain had come to power in 1940 as a national saviour, the one man who would get France the best deal following military defeat and the ‘desertion’ of the British army at Dunkirk. He would negotiate an armistice, but there would be no peace treaty. Part of France would remain under French control, the navy and the empire would not be affected, and the great general who had led the victory parade on the Champs-Élysées in 1918, the ‘Victor of Verdun’, would once again protect his people. The subsequent Vichy regime (described by one cynic as ‘a banana republic without the bananas’) was recognised around the world – even in the United States, which kept an ambassador in the spa town, France’s new capital, from 1941 to 1942.

In reality, what followed was the STO (Service du travail obligatoire), a forced labour programme which obliged 650,000 Frenchmen to work in German factories, the deportation of 24,000 French citizens on the sole grounds that they were Jewish, and the deployment of French police in the rafles (round ups) of 53,000 Jewish refugees who had fled to France for protection.

In the spring of 1945, de Gaulle’s government decided to put Pétain (who was still in Germany) on trial in absentia before a special court. It would be a symbolic ceremony with only one possible outcome, designed to unify the nation and heal the humiliation of defeat. But Pétain, inconveniently, decided to be present and, much to de Gaulle’s irritation, arrived in Paris in time to attend.

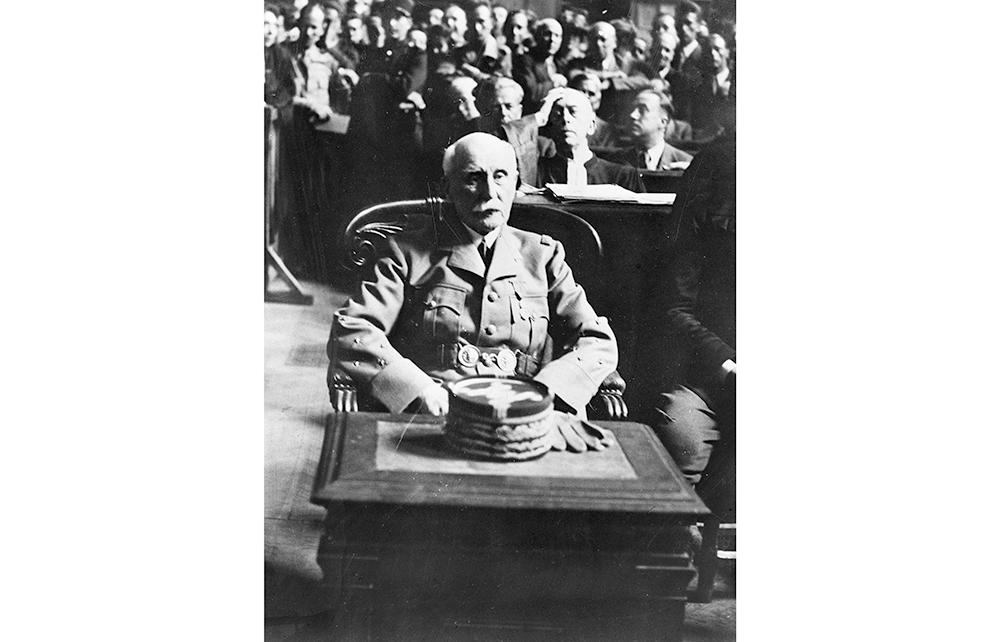

Throughout the hearing, before judges who had previously sworn an oath of loyalty to the marshal, Pétain sat in passive silence, leading many to wonder how much of the evidence he could understand. As a Marshal of France, he was given an ornate, cushioned throne rather than the dock. On this he slumbered, looking his age – 89 – although he was in many ways much older. Born during the reign of Napoleon III, he had been taught to read by a priest who had himself been born in the reign of Louis XV, 15 years before the French Revolution. The values that Pétain had absorbed as a child in the 1850s were already a century out of date.

Facing charges that he had been a pre-war member of la Cagoule (‘the Hood’), a terrorist conspiracy, and had plotted to seize power and make peace with the Nazis, he responded with a brief statement: ‘I was begged to come, and I came. I found I had inherited a catastrophic situation not of my making. Those who were really responsible hid behind me to deflect the people’s anger.’ Then he left his defence to the star of the show, Jacques Isorni, his youthful barrister.

Jackson frequently quotes from the diary of one conscientious juror, Jacques Lecompte-Boinet, a conservative Gaullist resister, who kept an open mind until the evidence was complete. He accepted that Pétain’s policies had sheltered many from deportation and was repelled by the hysterical loathing whipped up by the communist jurors. The PCF (French Communist party) had a guilty conscience. From 1939 to 1941, the years of the Nazi-Soviet pact, the party’s call for ‘international workers’ fraternisation against a capitalist war’ had gone much further than Pétain’s original appeal for ‘collaboration’. Outside the court, in the press and even on the jury, the PCF kept up an unrelenting pressure for douze balles –‘12 bullets’: execution by firing squad.

They had an objective ally in the show’s stage villain Laval, who appeared as a witness for the prosecution, even though he was awaiting his own trial. He claimed that the marshal had endorsed everything he himself had planned or accomplished: the handshake with Hitler in 1940, the policy of ever closer collaboration, the imposition of the Yellow Star, the addition of Jewish children to the deportation convoys, and even Laval’s notorious broadcast stating his desire for Germany’s victory. Laval was tried later that year, after which, gagged and strapped to a chair, he was shot. Had he been tried first, it is just possible that Pétain would have been acquitted.

Had Pierre Laval been tried first, it was just possible that Pétain would have been acquitted

One of the complications of Pétain’s trial, as Jackson points out, was a lack of clarity as to what constituted treason. Was it Pétain’s original decision to capitulate and seek an armistice, as de Gaulle believed? Was it his failure in 1940 to send the government to Algeria, where the army and navy were undefeated? Was it his refusal to leave France and join the Allies in North Africa after Germany occupied the Vichy zone in 1942? The fate of the 76,000 Jews sent to the death camps was largely overlooked.

In this unmapped legal jungle the defence was able to clear Pétain of membership of the terrorist conspiracy and of plotting to seize power, and Isorni’s brilliant closing speech reduced a high court, packed with Resistance and communist jurors, to complete silence. Isorni pleaded for an acquittal, and very nearly succeeded. The jury voted for death by only 14-13 – and added a request that the sentence should not be carried out. De Gaulle commuted the sentence to life imprisonment, and Pétain died six years later.

For the philosopher Simone Weil, who had fled to London in 1942, the armistice of 1940 – which had been widely welcomed by the French – was ‘a collective cowardice, a collective treason’. She added, thinking of Laval, not Pétain, that the word ‘traitor’ should be reserved for those who openly ‘desired the victory of Germany’. And the title of Jackson’s book raises the same intriguing question: was the national catastrophe of 1940-44 actually the failure of France, or was it primarily the work of one venal old man? And if it was France, why was one man paying for it?

It is because this question was never answered that Mauriac’s summary is valid today, and the trial of Pétain remains so important. In the final section of the story, Jackson traces the campaigns, from 1945 to the present day, of those who never accepted their hero’s guilt. Isorni’s attempts to win a posthumous pardon continued until his own death in 1995. And echoes of pétainiste loyalism can be heard over the years in the political causes of the extreme right, such as the terrorists of the OAS fighting against Algerian independence, in Jean-Marie Le Pen’s Front National (now, under his daughter Marine, known as the National Rally) and in the ineffective presidential campaign of the populist reactionary Éric Zemmour in 2022. Zemmour, in particular, with 7 per cent of the vote, turned out to be of little significance. But even readers who are not entirely convinced by Jackson’s analysis of France’s current political problems will find France on Trial an essential key to understanding the country’s recent past.

Comments