Once the working classes were allowed to vote it was inevitable that sooner or later they would elect a government which reflected their interests. That moment came with the appointment, in January 1924, of the first Labour government.

The circumstances could hardly have been less auspicious. There had been three general elections in as many years. No party had an overall majority. Labour, with 191 seats, was not even the largest, with the result that, throughout its short life, the government was entirely dependent on the goodwill of the Liberals, which soon ran out. With a couple of junior exceptions during the wartime coalition, no Labour MP had any experience of government. In the House of Lords, which, apart from the bishops and the law lords, was entirely hereditary, the party had virtually no support. It was, according to a witness at the time, ‘an untried body of men travelling in an unknown land surrounded by enemies’.

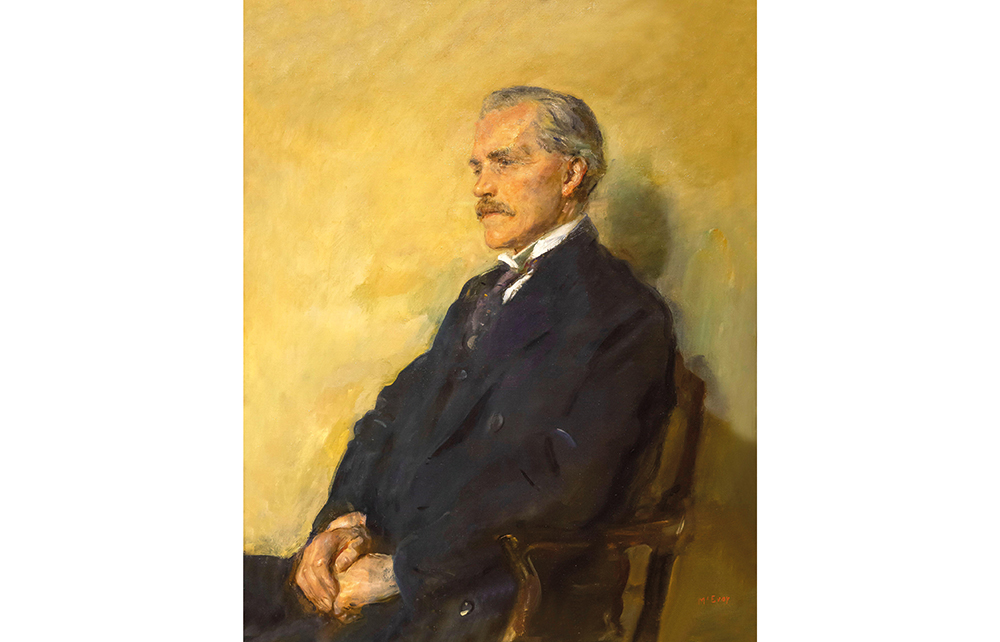

With no credible candidate for foreign secretary, MacDonald combined the job with the office of prime minister

The immediate problem, and it was the subject of much newspaper interest, was what the Labour ministers would wear when being sworn in as privy counsellors by the King. Visits to the palace required top hats and tails, which were beyond the means of all but a handful of grandees. The King obligingly relaxed the dress code.

In the main, the new government was composed of men of humble origins. Many had left school at 12, and one had worked from the age of nine. The prime minister, Ramsay MacDonald, although he soon adapted to the warm embrace of the establishment, was the illegitimate son of an agricultural worker. Philip Snowden, the chancellor of the exchequer, was the son of weavers. The home secretary, Arthur Henderson, was the illegitimate son of a domestic servant.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in