This is the second excellent book by Benjamin Balint to consider the cross-cultural perils of being a great writer after you’re dead. His first, Kafka’s Last Trial: The Case of a Literary Legacy, described legal battles over the residence of Kafka’s literary estate. This new one shifts the focus to a very different (and equally unusual) writer, Bruno Schulz, whose work has long been caught up in posthumous conflicts about who it most belongs to – that motley assembly of us selfish readers who actually read him, or those various governments competing to claim him as part of their national heritage.

Schulz’s brief success preceded one of the most tragic deaths recorded in the history of literature

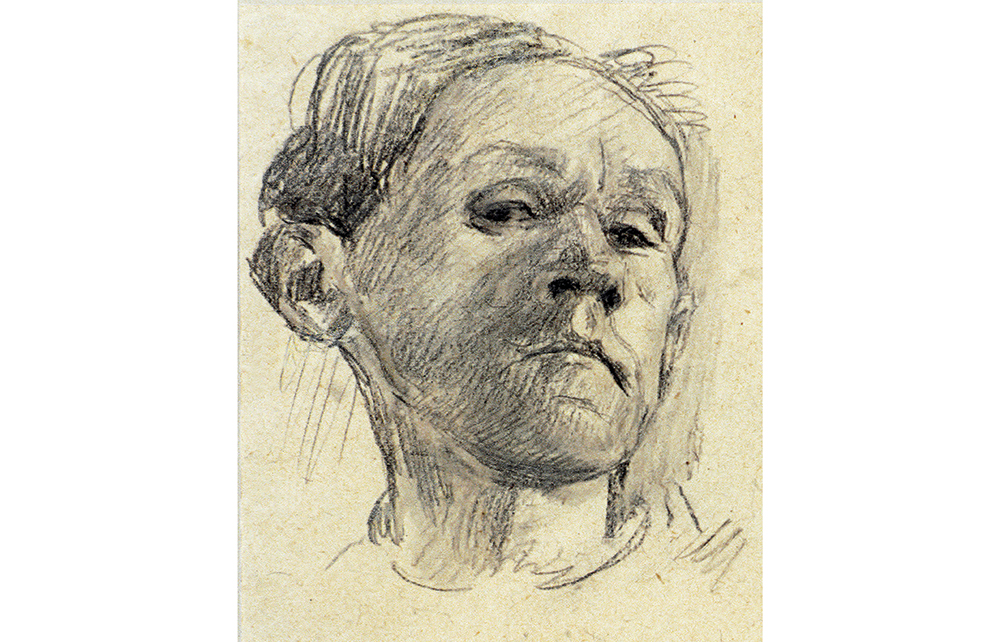

Born in 1892 in the wildly multicultural and polyglot Drohobych, Schulz grew up in a home ‘dominated by women’. His parents owned a textile store on the market square, and when Schulz wasn’t being adored by his mother, or ordered about by his much older sister, he played among scraps of cloth and trimmings, and imagined stories behind the facades of the silently looming mannequins, while the shadow of his broody father came and went (as he later would in Schulz’s fiction) like a Blakean demi-god, full of dark mutterings and forebodings. Schulz would eventually romanticise his childhood memories with all the power of a born storyteller – for it seemed that only by telling stories about the world could he acquire any control over it. ‘The most beautiful and most intimate thing in a man,’ he once said, ‘are his memories from youth, from childhood.’

Schulz grew up amid an effervescent tapestry of languages, cultures and nationalisms in what Balint describes as

one and a half cities: half Polish (the gentry), half Jewish (the merchants), and half Ukrainian (the peasantry). Its streets resounded with mixtures of Polish, Ukrainian, German and Yiddish.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in