Since this month, the UK government has been able to send mothers condolences for the deaths of children whom it would have been perfectly happy to allow to be killed in different circumstances.

This situation has been created by the expansion of the government’s baby loss certificate scheme, which was launched back in February. It allowed mothers who, since 2018, have experienced a miscarriage before 24 weeks of pregnancy, to receive ‘a certificate in memory of your baby’. Miscarriages after this point are registered as stillbirths. Last week, the scheme expanded to include all miscarriages prior to 2018.

If personhood can be conferred or defined then it can be withdrawn or redefined – a chilling thought

On its own terms I think the scheme is very welcome. I was moved to tears by the Today programme as listeners said how, after only hearing of the scheme that morning, they had registered losses mourned for decades. And yet I shook my head in bafflement as I considered how utterly incoherent the baby loss certificate scheme is when considered alongside the UK’s abortion laws.

Why does the scheme stop at 24 weeks – when any loss is classified as a stillbirth? Because that is the UK’s legal abortion limit in all but a negligible number of cases.

But that in itself raises an important question: how is it that the government could right now be sending a mother who miscarried at 23 weeks a certificate acknowledging her ‘lost baby’, while simultaneously scheduling an appointment for another woman at 23 weeks to ‘abort her foetus’?

Either way, the state has entered into a therapeutic exercise. Either it is dissembling to a miscarrying mother by referring to her foetus as a ‘lost baby’ or it is dissembling to the abortion-seeking mother by referring to her baby as an ‘aborted foetus’. It simply cannot be both ways.

It should never be the state’s role to therapise someone whose feelings don’t match reality. Nor should the state leave it up to mothers to define personhood, making such a thing a matter of preference or sentiment. If personhood can be conferred or defined then it can be withdrawn or redefined – a chilling thought. Personhood can surely only ever be recognised.

What then can be done about such profound incoherence? One big move in the right direction would to reduce the UK’s abortion limit. Such a suggestion will send plenty of people into hysteria, especially a certain type of America-brained liberal in a post-Roe world. But to many people’s surprise, the British 24 week limit makes us an extreme outlier in Europe.

Vociferous defenders of abortion in the UK are usually those whose politics inclines them to think that we should be, in whatever nebulous way, ‘more like Europe’. Yet over on the supposedly more liberal and progressive continent, abortion limits are generally lower than ours. In most countries the limit is around the end of the first trimester. In Belgium, Denmark, Finland, and Germany it’s 12 weeks. In France and Spain, 14 weeks. In Croatia and Portugal, ten. The UK is the joint highest at 24 weeks, along with the Netherlands. Iceland (22 weeks) and Sweden (18 weeks) take the macabre silver and bronze. According to the Center for Reproductive Rights (which, as you might guess, is not happy about this), 15 European countries also have mandatory waiting periods and 12 have pre-abortion counselling. Admittedly the UK, along with Finland, is supposedly more restrictive in that it does not officially grant abortions ‘on request’ but rather on ‘broad social grounds’, but this seems to be a distinction without a difference in practice.

Let’s say that we halved the UK abortion limit to 12 weeks. This would not be a descent into the kind of hellish, Handmaid’s Tale dystopia that haunts the dreams of Guardian columnists. Rather, it would simply bring us into line with our European neighbours, and cause things like the baby loss certificate scheme to make a whole lot more sense (though still not total sense, as far as this writer is concerned).

In Britain only 1 to 5 per cent of miscarriages happen between 12 and 24 weeks – the vast majority are before 12 weeks. But a small percentage of a lot is still a lot. There are around 250,000 miscarriages in the UK last year. Five per cent of that would amount to 12,500. If our abortion limit was cut to 12 weeks, this would mean that as many as 12,500 unborn children per year would be liberated from this strange limbo – one in which the British state is just as willing to allow them to be killed as it is to mourn them.

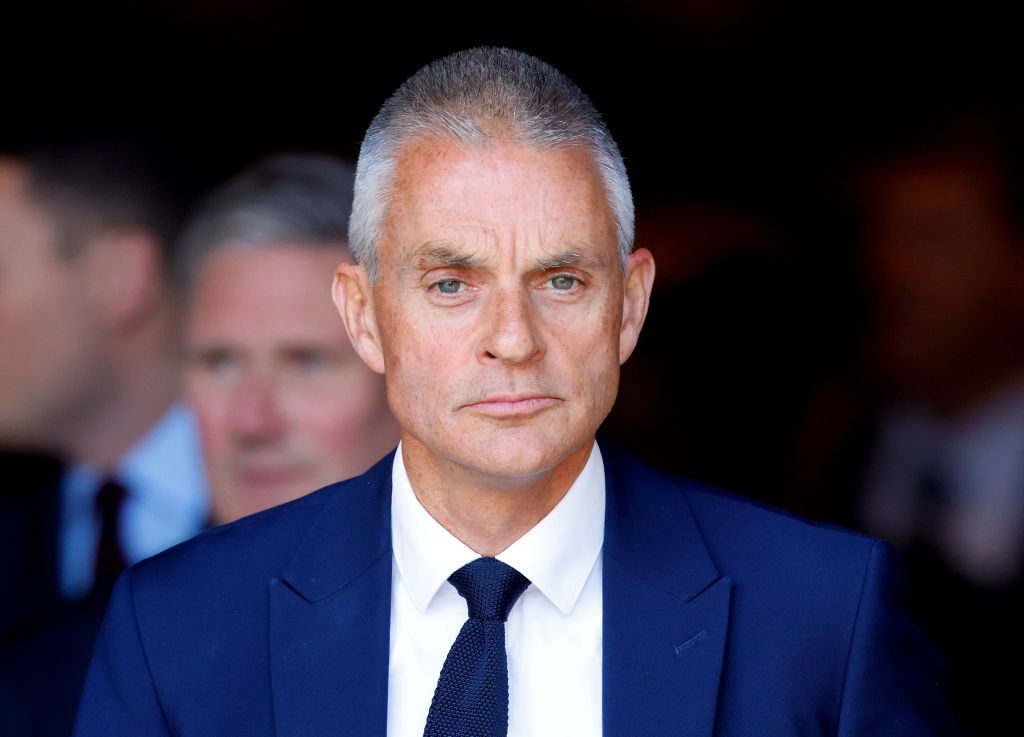

Rhys Laverty is an editor with The Davenant Institute and writer of The New Albion Substack.

Comments