From ‘Rupert Brooke’, The Spectator, 1 May 1915:

TO all men there is attractiveness in the combination of the soldier and the poet, and perhaps the combination gives a more satisfying pleasure to the countrymen of Sir Philip Sidney than to any other race. This is the reason why thousands of Englishmen mourn for Rupert Brooke who never knew him, and possibly, till a few days ago, never heard of him. They read the brief details of his life and accomplishment, and at once their sorrow was real and, in a sense, personal. Rupert Brooke was distinctly one of the most promising of our poets. He had fire, imagination, a joy in life, a classical taste, an Hellenic eye for beauty and grace. As in the case of Donne, whom he greatly admired, his poetry was weighted by his intellect, and sometimes seemed harsh and knotty. Less often it was obscure. But the war was to him a tumultuous mental and moral experience. We think we are not deceived in noticing a remarkable change in his verse. He wrote five sonnets, which were published in New Numbers last December, and from these most of the earlier verbal clevernesses and oddities had fallen away. These sonnets had a steadier glow of feeling, more calmness yet more strength ; they spoke of sacrifice, and of death coming to the young who loved to live, and yet they were not over- heated but serene and triumphant. The emotions of the war had brought a young poet a long stage nearer to stability and maturity. He pondered on those public, emotions even while he served actively, and returned them to his countrymen in a moving form that was musical and (for himself) prophetic. These sonnets stand among the few fine poems prompted by the war.

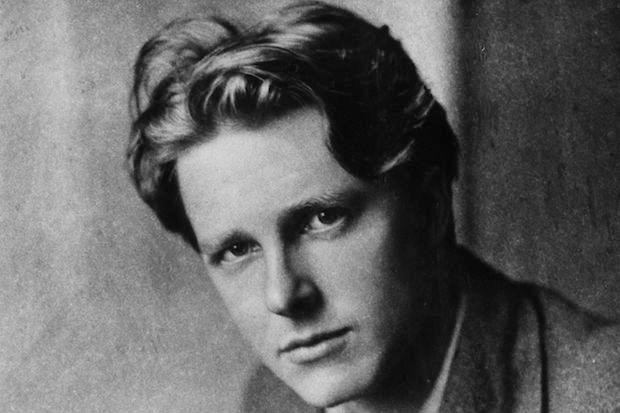

Rupert Brooke was the son of a house-master at Rugby and was born in 1887. He played cricket and football for the school, and won the poetry prize fora poem on “The Bastille.’ At Cambridge he was at King’s, and was elected in 1913 to a Fellowship after writing a critical appreciation of John Webster. After taking his degree in 1909 he lived mostly at the village of Grantchester, near Cambridge. In 1913 he travelled is the United States, Canada, and the South Sea Islands—making a pilgrimage of affection and literary reverence to Stevenson’s home in Samoa—and readers may remember the letters, full of enjoyment and distinguished by strokes of humour and touches of beauty, which he contributed to the Westminster Gazette. His only volume of poems was published in 1911. Most of his late, poems were published he New Numbers, a poetical quarterly which is published at Ryton, Dymock, Gloucestershire, and in which he collaborated with Mr. Lascelles Abercrombie, Mr. John Drinkwater, and Mr. Wilfrid Gibson. Last September he received a commission in the Royal Naval Division. He served with the expedition to Antwerp, and at the end of February he sailed for the Dardanelles. A sunstroke in April was the beginning of a mortal illness, and he died on Friday week in a French hospital ship at Lemnos—died in the Isles of Greece for which he must have shared the lyrical love of Byron. At least, the echo of Byron’s lyricism about places which moved his heart and memory and stirred his sense of beauty some- times sounded in Rupert Brooke’s verse.

Rupert Brooke was not, however, an imitator of any one. He approved the taste of his own academic generation, which gave to Donne more honour than even the centuries of neglect seem to many of us to entitle him. Dryden’s praise and Pope’s “sincere flattery” say too little about Donne for the young generation of readers of poetry. Bet if Brooke loved the packed intricacies and amazing metrical erudition of what Dr. Johnson called the Metaphysical School. He also learned from the splendours of Webster in The Duchess of Malfi. Here, again, was a tribute due to genius neglected through centuries, and he paid it as thoroughly ex Lamb, who well knew that Webster had the true gift of tragedy, and could make terror noble, pity purifying, and even “affrightments” decorous. No poem of to-day is better known to Cambridge men than Brooke’s yearning for his English home called “The Old Vicarage, Grantchester,” which was written in Berlin and is republished in Georgian Poetry (The Poetry Bookshop, Is. 6d. net). The objective of the conventional Sunday walk, known to many as “the Grantchester Grind,’ is seen through a medium of transforming tenderness; and the words are accepted and treasured by undergraduates perhaps because the amiable flippancy makes it perfectly respectable for them to fall in with its mood. For the matter of that, undergraduates may not before have detected the beauty of the neighbourhood of the pool where Byron used to swim.

Comments