In February 1924 the Hotel Florida, a ten- storey marble-clad building with 200 rooms, a glass-roofed atrium and red plush furnishings, went up on Madrid’s Gran Via. Along with the Ritz in Paris, certainly the most celebrated hotel in the literary world, the Florida became, during the two-year battle for the capital waged between Franco’s nationalists and the republican forces, the meeting place for an eccentric, glamorous and self-important assortment of war tourists, zealots, opportunists, romantics, dreamers, buccaneers and writers who had come to observe the fighting, file dispatches of variable truthfulness and proclaim loyalty to the republic. In its own way, the Florida has become as emblematic of the Spanish civil war as Robert Capa’s controversial photograph of the militia soldier shot as he leaps across a ditch.

Six of its visitors form the basis of Amanda Vaill’s new account of the war, brought to the Florida by a shared commitment to the cause and their own particular ambitions and dreams. There are Hemingway and Martha Gellhorn, the best known couple, whose exploits and murderous quarrels have been amply chronicled elsewhere. More interesting, there is Arturo Barea, tormented night-time censor in the propaganda department, whose job it was to ensure that nothing got out of Madrid that suggested anything other than a republican victory, and Ilse Kulcsar, a curly-haired Austrian political exile with whom he fell in love, who spoke eight languages and had come, as she saw it, to bear witness. Barea makes an attractive character, railing against the levity and posturing of the foreign reporters, behaving as if they were the ‘main actors in the war’.

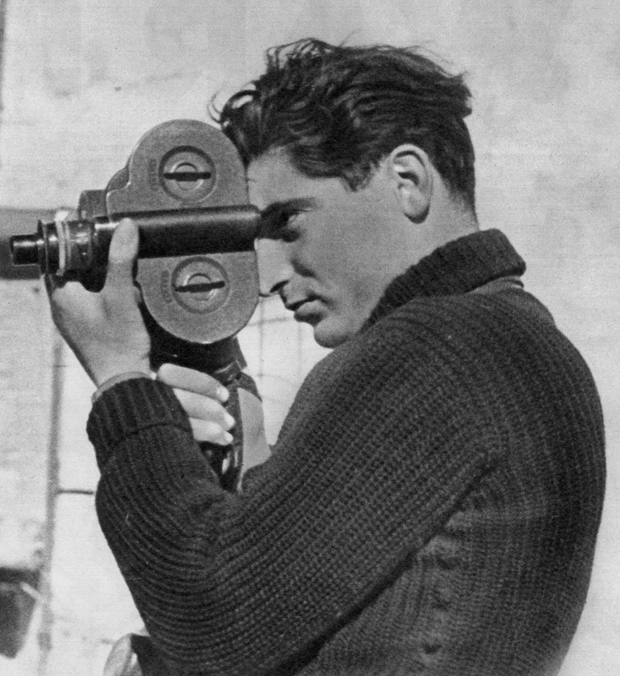

And there was Robert Capa, the dark and very attractive Hungarian photograher, who had just turned 23 and changed his name from André Friedmann, thinking Capa sounded crisper and more memorable, who arrived with the boyish and foxy looking Gerda Taro, who had also changed her name, from Gerta Pohorylle, for much the same reasons.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in