On 14 October 1942, the 23 Swiss members of the International Committee of the Red Cross met in Geneva to decide whether or not to go public with what they then knew about Auschwitz and the Nazis’ extermination plans. When they emerged two hours later they had voted, almost unanimously, to remain silent. As did the US state department, the British government and the Vatican — all in possession of the same evidence of mass murder across German-occupied Europe.

The reasons given ranged from the danger of reprisals against Allied PoWs to the need to focus on military targets, and thus shorten the war. And, most importantly, because of a profound unwillingness to believe what they had been told. It was not until late December that public statements of condemnation were made, and Anthony Eden told the House of Commons that the Nazis were ‘pursuing a bestial policy of cold-blooded extermination’. Even then, no action was taken.

Exactly who knew what when about the Holocaust has been the subject of countless books, debates, reports and articles since the end of the second world war. Jack Fairweather, a former war correspondent for the Washington Post, has now unearthed remarkable, long-neglected material about the early days of Auschwitz, and how, from the camp’s very beginnings in 1940, information was emerging regularly about its murderous purpose.

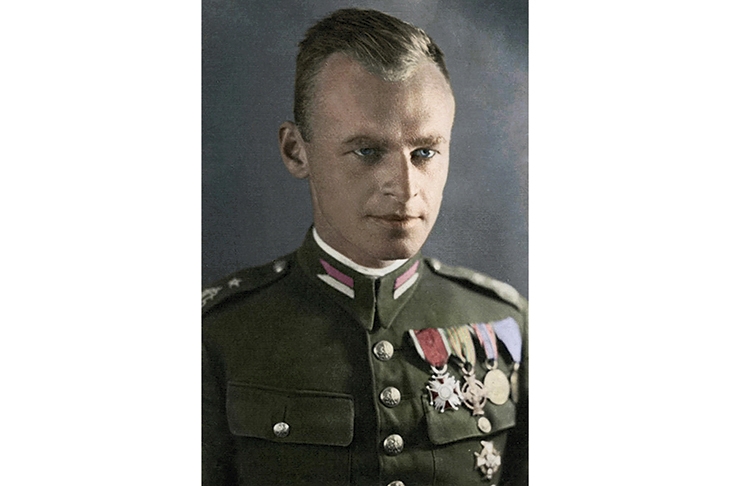

In 2011 Fairweather learned about a band of Polish resisters who had repeatedly risked death to get accurate documentation about the killings in Auschwitz to the underground in Warsaw and from there to the Allies in London. A report by a man called Witold Pilecki had come to light in the 1960s, but it was some time before its coded entries were deciphered and not until after the collapse of the Soviet Union that more material was discovered buried in Poland’s state archives.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in