‘We came as adversaries, we stayed as allies, and we leave as friends,’ British prime minister John Major told crowds in Berlin on 8 September 1994, thirty years ago today. The last 200 British, American and French soldiers withdrew from Berlin that day, leaving the city without a foreign military presence for the first time since the Second World War. This was supposed to be the end of history. In reality, a new chapter had already begun.

The presence of the Western Allies in post-war Germany is still remembered fondly today. There are events marking the 30th anniversary of their departure, and many traces of their occupation remain. Take the former airbase RAF Gatow in southwest Berlin, which played a key role in supplying West Berliners with food and resources during the Soviet blockade of Berlin in 1948. It’s now a military museum with aeroplanes from its time as an RAF base.

In the end, even the Soviets appeared as a largely benevolent force to many of their former enemies

British occupation even left a much-loved culinary legacy, the currywurst. The German Chef Herta Heuwer is usually credited with the idea of covering grilled pork sausages with ketchup and curry powder, but she procured those ingredients from British service personnel stationed in Berlin.

The humble currywurst has its own memorial plaque, dating its birth to 4 September 1949. Germans have never looked back. Last year, VW employees alone ate over 8 million portions of currywurst. Earlier this week, it got a shoutout for its 75th birthday from the German Embassy in London.

Even beyond greasy pork covered in ketchup and curry powder, the Allied occupation of West Germany and Berlin is a remarkable success story. As one of the first Britons to set foot in the former capital of the Reich after the war, Joan Bright saw the awful state it was in first-hand.

The 35-year-old administrative officer had once dated Ian Fleming and is said to have been his inspiration for Miss Moneypenny. But there was nothing glamorous about the scenes that awaited her when she arrived in Berlin in June 1945, charged with the task of preparing a major conference as Winston Churchill’s trusted assistant. The German capital was a mess, from the burnt-out shell of the Reichstag – the parliament building for which Hitler had found so little use – to the battered Brandenburg Gate and the furtive German civilians who scurried in and out of ruined houses.

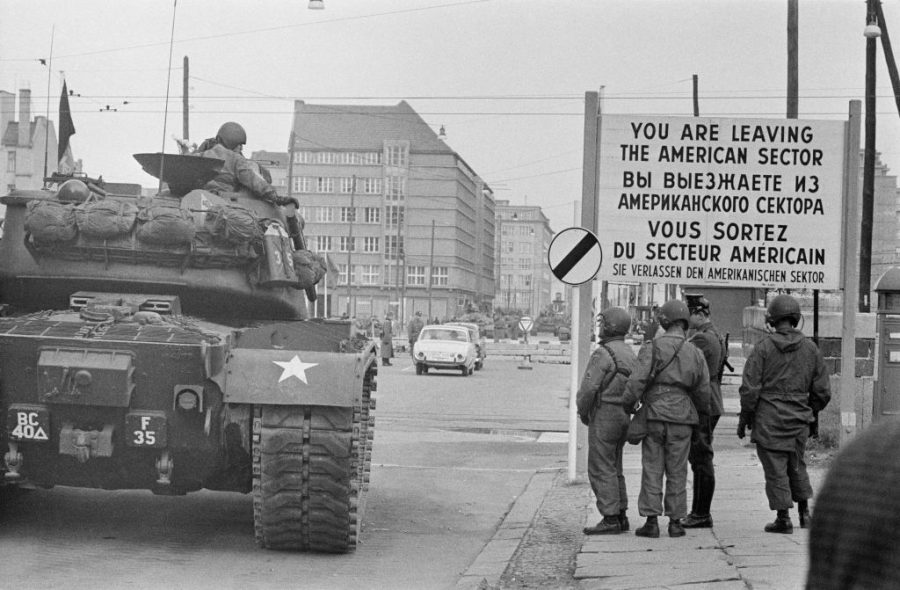

At the Potsdam Conference that Miss Bright helped organise, a formal military government was established for Germany. This Allied Control Council, run jointly by Britain, the US, France and the Soviet Union, was supposed to act as a temporary government for Germany. But for practical reasons, each victorious power had its own zone of occupation to run. The same applied to Berlin, which was also split four ways, even though the former German capital sat within the Soviet Zone.

Emerging Cold War hostilities soon changed the nature of this arrangement. With an ideological fault line running right through the defeated Germany, the question of what to do with the people who had aided their Führer in a genocidal quest to conquer all of Europe suddenly became secondary. The bigger question now was how each side could tilt Germany’s enormous geopolitical and economic weight in their favour.

The Soviet Union and the Western Allies found two different answers to this. Moscow needed resources. They took what they could from their zone and, after 1949, from the newly founded East Germany. The West needed a strong Germany as a bulwark against communism. So the US poured $1.4 billion of Marshall Plan aid into their zones and from 1949 into West Germany. The East paid over 90 per cent of German war reparations. The West had an ‘economic miracle’.

Two very different occupation experiences emerged. West Germans largely saw well-disciplined soldiers arrive and quickly turn from enemies to providers and then to protectors and partners. East Germans suffered the blunt fury of the Red Army with an estimated 2 million rapes and other atrocities. Neither the Soviets nor their German stalwarts had much time for pity in light of what the Wehrmacht had done on the Eastern Front. An official narrative of liberation from fascism was established but many East Germans found it hard to feel liberated, especially when soon after their 1953 uprising was brutally crushed by the Red Army.

The relationship between East Germans and their occupiers changed somewhat over time. While the Soviet Union continued to station up to half a million soldiers in East Germany at any time during the Cold War, they tended to be segregated in their barracks.

Meanwhile, East Germans learnt Russian at school, watched Soviet fairytale films at Christmas and some were sent to Moscow to study. When Mikhail Gorbachev introduced reforms in the USSR in the late eighties, many intellectuals felt inspired. When he visited Berlin for the 40th anniversary of the GDR in 1989, crowds chanted ‘Gorby, help us!’ In the end, even the Soviets appeared as a largely benevolent force to many of their former enemies.

When the Berlin Wall fell, followed by the reunification of Germany in 1990 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, it seemed the horrors of the 20th century were finally over. It seemed there would be no more wars, and the Russians wanted this reflected in the leaving ceremony in Berlin. They too wanted to go as friends and asked to march out of Berlin shoulder to shoulder with the Western Allies.

But Cold War animosity was not so easily forgotten. American, British and French troops planned their last military parade in Berlin on 18 June 1994 alone. When Russia asked to join with an honorary unit and an orchestra, this was denied. The date was deemed too close to 17 June, the day on which day the Red Army had crushed the East German uprising in 1953.

The Russians were also excluded from the farewell ceremony on 8 September 1994. They ended up staging their own a week earlier. On 31 August, thousands of their soldiers marched through Berlin singing in accented German, ‘Germany, to you we reach out our hand as we return to our fatherland’. Chancellor Helmut Kohl looked on, but Russia marched alone. Hans Jung, an East German translator involved in the event, remembered that ‘the Russians were not amused’.

Despite this snub, the summer of 1994 was jubilant. It may have been naive, recalled Jung, but when the Russian troops left, many thought that peace would last forever. The optimistic end-of-history mood would soon drive Western democracies towards some of the lowest military expenditures in modern history and Germany into Russian energy dependence.

As the former Cold War enemies marched out of Berlin on different dates and in different directions, the moment could not have been more symbolic. Russia and the West were to remain at odds on the eastern fringe of Europe – even if their worlds no longer collided in Berlin.

Comments